Portraits From the Front Line

Until recently, Richard Meichtry made sure the perishables weren’t perishing. Traci Holmes doled out deli meats, and Blanca Marquez bagged milk and eggs.

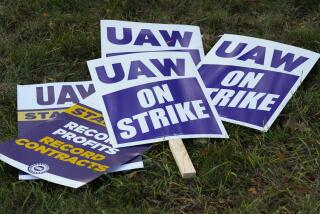

Now, they are among 70,000 grocery workers in Southern California who have been walking picket lines since Oct. 11.

For most pickets, supermarket work is a career. Grocery stores hire plenty of high school and college students, but the wages and benefits have been good enough to keep people on payrolls for years.

Nationally, 45% of union supermarket workers are 45 or older, according to the United Food and Commercial Workers. And 60% are women, up from 47% in 1980. The seven UFCW locals representing striking and locked-out workers in Southern and Central California don’t break out demographic data on their members, but they say the workforce here is more diverse than in the country overall, where nearly 79% of union supermarket workers are white.

“Supermarkets mostly reflect the communities that they’re in,” said Greg Denier, UFCW communications director. “You go to Vons, and you see mothers and daughters and people who’ve worked there forever.”

Here’s a look at some of the people carrying the picket signs:

Produce Worker

Tracey Richardson has tried her hand at many things. There was a four-year stint in the Navy, where she trained as a welder before becoming a military police officer. Then she installed low-voltage lighting, washed dishes and worked as kitchen help in a restaurant.

It wasn’t until she interviewed at a Pavilions store in West Hollywood, Richardson said, that she found her niche.

Richardson started as a “courtesy clerk” -- the industry term for grocery bagger -- and quickly moved to the deli, where she ran the cheese operation. Then Richardson set her ambitions on the higher-paying produce department (“because, basically, I’m a vegetarian”), rising to manager for a time until store closings eliminated her job.

“I guess it was for the best because I’m just not a manager-type person,” Richardson said with a laugh. She nonetheless is a “picket captain” supervising other strikers during long shifts in front of the store where she works.

“I’ve always been good with my hands and went after the guy kind of jobs,” she said. “It takes skill to get those apples balanced and looking good with no stickers showing -- and then someone pulls from the bottom and there are apples all over the floor.”

The current dispute with store ownership has left Richardson questioning the direction her life has taken.

“I’m thinking, did I make the wrong decision spending 12 years in this company? But I didn’t go the college route, and the supermarket business seemed like a good idea,” said Richardson, who makes the maximum $17.90 an hour for her job category.

Richardson said she sometimes thought about going back to school to explore her interests in photography and art, perhaps pursuing work as an illustrator. The strike has provided new subject matter: “I’ve been taking lots of pictures of our motley picket crew,” she said.

One recent art project involved making lamps out of unusual materials, such as cardboard tubes. “Now everything is a possible lamp for me,” she said.

Richardson has found most customers sympathetic, some bringing food and water. But not all support the strike.

“Some people tell us, ‘I don’t believe in strikes,’ ” Richardson said, but she’s unfazed. “This is what this country is made of, people standing up and trying to better themselves.”

Grocery Bagger

A former housekeeper, Blanca Marquez saw her job bagging groceries at Ralphs for $6.95 an hour as a passport to a better life.

“You can be promoted to bakery or a cashier one day,” she said. “I didn’t want to stay a wrapper for the rest of my life.”

A divorced mother of three children who lives with her sister in a Hollywood apartment, Marquez said her pay wasn’t enough to raise a family on. But she took the part-time job eight months ago in hopes of eventually getting enough hours to qualify for fully paid benefits.

“I need these benefits for my kids,” she said, wiping her face, hot from long hours picketing the Ralphs store she once helped keep in order on La Brea Avenue at 3rd Street in Los Angeles.

Born in Mexico, Marquez, 36, said this was the first strike she had ever been in. She’s committed for the long run, with her sister’s financial help.

Still, worries about her future are keeping her up at night. Marquez also is concerned about the upcoming holidays if the strike drags on. Her 16-year-old daughter, who attends Hollywood High School, wonders whether she will get any Christmas presents.

“They say, ‘Mom, are we going to get gifts for Christmas? Just one, right?” and I tell them, ‘I just don’t know,’ ” she said.

Full-Time Clerk

Ken Miller is a 51-year-old clerk at Albertsons in San Marcos, north of San Diego, and a walking testament to the importance of medical benefits. Health benefits are the central issue in the contract dispute between the UFCW and the major grocery chains, and for the last week Miller has been walking the picket line to try to keep them.

He has been on the job 33 years, shelving his real estate license and passing on other opportunities to keep hold of the insurance that carried him through two knee surgeries and a quadruple heart bypass, and kept the family solvent when his daughter had a skull fracture at age 12.

“If I was working at Wal-Mart, the taxpayers of California would have paid for my heart surgery and not my medical insurance,” said Miller, whose three daughters are grown now.

As one of just two full-time clerks at his store, Miller readily acknowledges that his $17.90-an-hour wage adds up to a bigger paycheck than many of his colleagues get. But, he said, “our store’s a big happy family. Everybody gives heart and soul.”

Miller said he loves chatting with the store’s regular customers and has running jokes with some about how many years, months, days, hours and minutes he has until retirement. “Everybody takes everything so seriously. Banter is a lost art,” he said.

His world outside of work, Miller said, revolves around his family, including his wife of 27 years. “I’m so proud of my daughters,” he said. “And make sure to say that my wife’s a real sweetheart.”

Deli Clerk

Traci Holmes thought she had landed her dream job six months ago, when she began working as a deli clerk at the Vons on Mulholland Drive in Woodland Hills.

The cash-strapped divorced mother of two school-age children said she needed a job with good benefits. She researched careers and targeted the grocery industry, taking a 16-week training course at the West Valley Occupational Center to increase her odds of getting hired.

Holmes, who also works at a Vons in Van Nuys, earns $7.55 an hour with an extra 50 cents thrown in for work after 6 p.m. There’s time-and-a-half pay for Sunday work and triple-time for holidays, plus medical, dental, prescription, vision and pension plans.

But it is the bond with co-workers and customers that is the best part of the business, Holmes said.

“I’ve worked in a lot of places since I was 16, and I’ve never felt a family atmosphere like we have,” said Holmes, a high school graduate with a resume that includes fast-food, office and construction work.

Now, Holmes watches with dread as her new life threatens to disintegrate. Holmes estimates that the company’s last contract proposal would cost her $4,000 a year in various premiums, deductibles and co-payments for her family.

“If the medical benefits change, I can’t afford it. I would have to move into a one-bedroom apartment and put up dividers for privacy,” Holmes said.

As it is, the 34-year-old Holmes shares a bedroom with her 9-year-old daughter while her 11-year-old son takes the other bedroom. Holmes said her ex-husband lives in Massachusetts.

“I’m scared; I’m really scared,” Holmes said. “This is like a huge bomb going off in front of me.”

Holmes puts in nearly 40 hours a week, packing in as many night and weekend shifts as possible. That maximizes pay but minimizes time with her children, who are cared for by family members when Holmes is absent.

Precious time off is arranged around the children, cooking together and playing board games, Holmes said.

“I want my kids to have more than I did,” Holmes said. “My kids get it. They understand that you have to fight for what you believe in.”

Produce Manager

He has tried graphic design and college business courses, but after 26 years Richard Meichtry still is in the grocery business.

Born and raised in Van Nuys, where he still lives, Meichtry signed on as a clerk at age 18 at what later became Ralphs. He was working at a swap meet at the time and very anxious to move on. “I used to stop by every couple of days to see the store manager until they got sick of me and hired me,” he said.

Today, he makes $18.90 an hour as a produce manager at Ralphs in Century City, where he works six days, runs the department and sets the schedules of five other people. Meichtry, 44, said he babies the perishables under his charge “so that I send as much as I can to the check stand and as little as possible into the trash.”

His two boys are grown now, but for years he was on a 6 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. shift that allowed him to pick up the kids, make the doctor runs and cook dinner while his wife was at work.

These days, “I make a pretty decent check. There’s always food, and we pay our bills,” Meichtry said. “But we have to be careful with money like everyone else.”

He and his wife drive 1992 and 2000 Hondas and spend their free time hunting down and refinishing old furniture and tending to their garden’s succulents and newly potted roses.

“You can fix it the way you want, and you can see things from being small, growing and to transplanting it,” he said of his garden. “Maybe that’s why I like produce. As the seasons change, you have new and different things. I look at it as moving art.”

Check-Stand Cashier

Dianne Murphy, 50, has worked at one place her entire career: Ralphs. She started as a cashier 32 years ago and still is a cashier, making $17.90 an hour.

Murphy pays $800 a month for a one-bedroom apartment near her job. She’s saved some money, but if the strike goes on more than a month or so, she’ll be in trouble financially.

“You know, $17.90 is not that much an hour in Los Angeles,” she said. “The government gets their take ... then you’ve got your gas bill, the lights and then God forbid, your car goes out,” she said. “All we want is an equal chance. We will pay more for health care, but not so much at once. It’s a slap in the face.”

These days, she’s hoarse from shouting on the picket lines in front of her Ralphs store on La Brea at 3rd Street in Los Angeles just a few blocks from where she went to high school. Her knees are sore from walking.

But Murphy, a divorced mother of a grown son, is more worried about her younger co-workers with small children, suddenly faced with no income.

She also worries about the elderly customers she’s come to know at Ralphs, even encouraging them to cross picket lines to shop there, because she’s worried they’ll get lost if they try to find a new store. “They aren’t used to going anywhere different,” she said. “My elderly people, I don’t want them to get lost out there.”

These days, to keep her perspective, Murphy spends time with her nieces and nephews, several of whom are foster children adopted by her sister in Hawthorne.

“They are what keeps me going,” she said.

Part-Time Cashier

Outside the Vons store in Carlsbad, north of San Diego, Teri Latasa stands with her picket sign near the entrance. “Are you going to cross my picket line?” she asks people going inside. She’s disheartened when they disappear into the store, but she’s not about to give up.

“I’m a cancer survivor. I had a mastectomy four years ago. I went through chemo and lost my hair and all that,” said Latasa, 43, who now has her blond hair pulled into a ponytail. “That’s what made me want to do this” strike.

Her husband is a fleet car salesman at a dealership, but the job doesn’t come with benefits. Without the medical insurance provided through Vons, Latasa said, “I would have lost my house; I would have lost everything” paying for breast cancer treatment.

Latasa grew up in Carlsbad and became a courtesy clerk at Vons at 18. After 25 years, she still doesn’t have full-time hours, but she has moved up to cashier and helps run the front end of the store. Two days a week, Latasa takes courses she hopes will someday land her a job as an oncology nurse.

She has a grown daughter, a granddaughter who turns a year old this week and is raising her 13-year-old niece. She makes stained-glass windows for friends and has one on display at her church. What else? Latasa doesn’t hesitate: “I love the beach; we love to go boating. We make a big dinner and have everybody over -- I like to do all the things that normal people like to do.”

--- UNPUBLISHED NOTE ---

On February 12, 2004 the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, which had stated repeatedly that 70,000 workers were involved in the supermarket labor dispute in Central and Southern California, said that the number of people on strike or locked out was actually 59,000. A union spokeswoman, Barbara Maynard, said that 70,000 UFCW members were, in fact, covered by the labor contract with supermarkets that expired last year. But 11,000 of them worked for Stater Bros. Holdings Inc., Arden Group Inc.’s Gelson’s and other regional grocery companies and were still on the job. (See: “UFCW Revises Number of Workers in Labor Dispute,” Los Angeles Times, February 13, 2004, Business C-11)

--- END NOTE ---