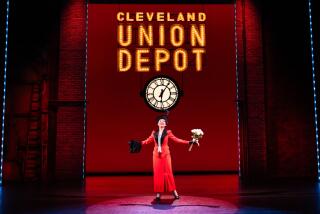

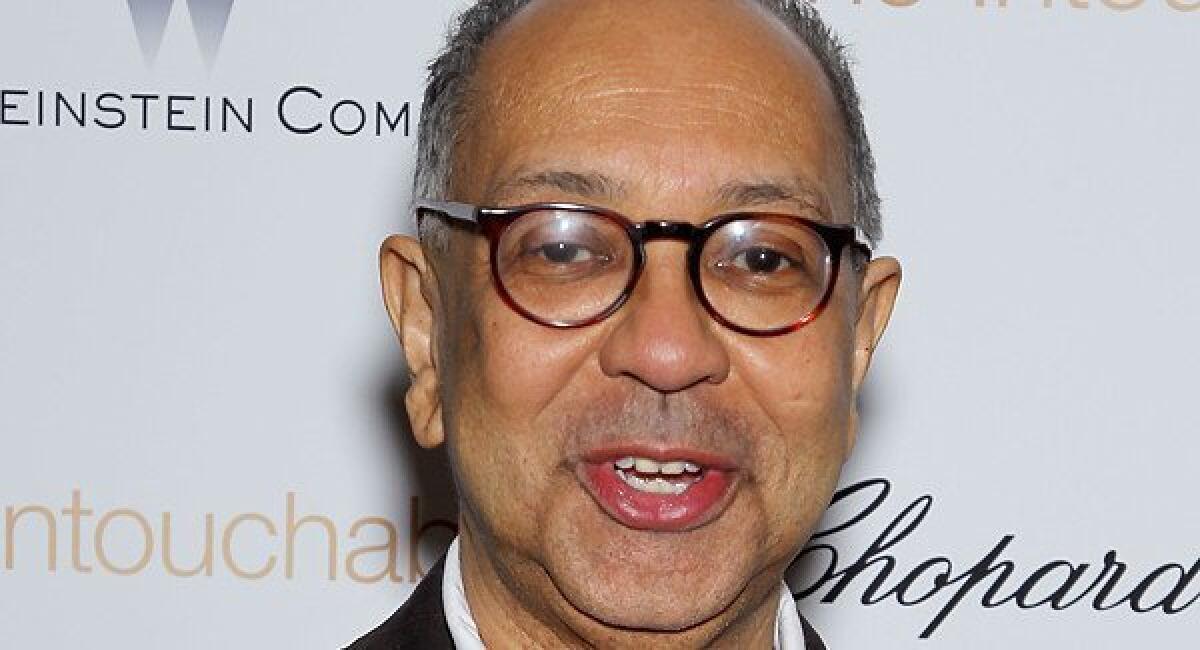

Why George C. Wolfe considers himself a lucky guy

— George C. Wolfe is flummoxed.

He’s describing the gestation of “Lucky Guy,” the Nora Ephron play he is directing with Tom Hanks playing an ambitious and cocky New York newspaper reporter.

It began, he says, with Ephron asking him: “What’s more fun than hanging out with the boys in the bar?” It ended, nine months later, with a phone call from her agent saying she had died.

“I didn’t even know that Nora was sick until the actual day she died,” he says, sitting in a Midtown Manhattan coffee shop on a rainy spring afternoon. He flips through a notebook. “This was her last email to me: ‘I am better. Complicated story. Hope all went well in D.C.’ It’s dated June 18th. Eight days before she died.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

“And then it was, ‘Whaaaat’? and then, ‘a memorial service’? And then, ‘We’re casting.’ And then, ‘We’re going into rehearsals.’ And now it’s up and we’re opening,” Wolfe said. “This is my 13th Broadway show and I’ve never had an experience as amazing and complicated as this. I’m still going, ‘Huh? Huh? Huh?’ ‘Wow. Wow. Wow!’” The play opens Monday at the Broadhurst Theatre.

Wolfe’s rapid-fire speech echoes the snappy dialogue of “Lucky Guy.” Ephron’s swan song is the real-life story of Mike McAlary, the tabloid reporter who swiftly rose through the ranks of the city’s most famous bylines in the 1980s and early ‘90s until a mix of naivete and hubris brought him crashing down.

He was able to redeem himself — winning a Pulitzer Prize for uncovering an ugly tale of police corruption and venality — shortly before he died of colon cancer at 41.

Ephron had worked as a reporter at the New York Post in the early years of her career, before the magazine columns and books, and before Hollywood claimed her as the screenwriter of “Silkwood,” “When Harry Met Sally” and the writer-director of “Sleepless in Seattle,” “You’ve Got Mail” and “Julie & Julia,” among other films.

McAlary’s obituary, Wolfe says, inspired her to create a film-noir valentine to the city she called home and the people, mostly men, who competed to capture it.

When Wolfe read the play, he immediately recognized the urban stew of danger and ambition. He moved to the city in the 1980s, was promptly mugged, then had his first play, “The Colored Museum,” produced at the Public Theater.

“Nora just had an incredible love for this world and these people and their passions and foibles,” Wolfe says. “The kind of self-destructive urges — stay up around the clock, drink all night, eat terrible food, drop dead in your 40s — all in the service of a getting a great story. The play is chock-full of the romanticism that, beneath a sweet cynicism, we are knights righting wrongs.”

FULL COVERAGE: 2013 Spring arts preview

Among those flawed knights was McAlary, played by Hanks in his Broadway debut. When Ephron told Wolfe that the actor she had directed in two hit movies wanted to play McAlary, a piece of the puzzle fell into place. It didn’t bother the director that the play would be carried by an actor whose last stage experience was in a 1979 off-off-Broadway production.

“I’d thought it would be fascinating to have a person who the audience would want to follow down a dark alley,” Wolfe says. “Tom has an incredibly refined charm muscle that makes them go, ‘Oh, I want to follow this guy on a journey wherever he takes me.’”

McAlary is arguably one of the most complex, narcissistic and hard-boiled characters on Hanks’ résumé. The actor himself has described him as a “jerk.”

The nadir of the reporter’s career came when he wrote a series of articles accusing an African American woman of falsely claiming rape when she had, in fact, been attacked. His redemption came through stories of the police officers who assaulted and sodomized Abner Louima, a Haitian immigrant in their custody. Four officers were convicted in the case.

Wolfe grimaces when asked if Hanks had any problem with some of the less virtuous aspects of McAlary’s character. “I’ve spent my life looking for unlikable characters,” he says, adding that it never even came up. His life as a director for the stage has included the landmark Broadway productions of “Angels in America,” “Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk” and, most recently, the acclaimed revival of “The Normal Heart.”

With “Lucky Guy,” Wolfe says: “It’s been fun playing with Tom to rouse all those qualities of a fearless, charming, innocent man who makes brilliant decisions and stupid decisions with the same ferocity. That really intrigues me.”

PHOTOS: Nora Ephron - A life in pictures

He finds something quixotic in both McAlary and Hanks. “There are signs that say, ‘Do not enter!’ And McAlary just goes charging in full speed ahead. ‘Oh, I just smashed my face? Well, I’m going in again.’ And Tom has channeled that fearlessness with which he approaches material with that same kind of fierceness. It’s been fascinating to watch him transpose certain strengths that he has as an actor so that they embody certain weaknesses in McAlary.”

Ephron shared with the characters of “Lucky Guy” a “ferocious desire” to tell a good story, Wolfe says.

They had known each other casually before they started meeting on average once a week to work on the play. He says he dealt with several Noras: the journalist, the storyteller, the smart, savvy, funny New Yorker, the girl who had been in the bar with the guys.

“We had a smart, tough, fun collaboration,” says Wolfe, noting that Ephron would often surprise him with treats that were invariably, as she might put it, “the best caramels ever!”

They went through about six or seven drafts of the play, which she would churn out with amazing speed.

“I remember telling her, ‘Nora, you don’t have to rush,’ but she was operating under the most extraordinary timetable imaginable,” Wolfe says. “The focus of that, the purity of that — and I know that’s a loaded word — was astonishing. The creative process appeared to be normal and it was normal but only because of this phenomenal grace with which she approached it. I don’t think I would have been so aggressive in my notes if I’d known she was sick.

“But you’re operating inside a scenario and only later do you find out that there was another scenario going on at exactly the same time! It’s mind-boggling and transformative and inspiring and humbling,” he says. “And I don’t humble easy.”

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

Depictions of violence in theater and more

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.