Asad Faulwell paints the tense landscape where Middle East meets America

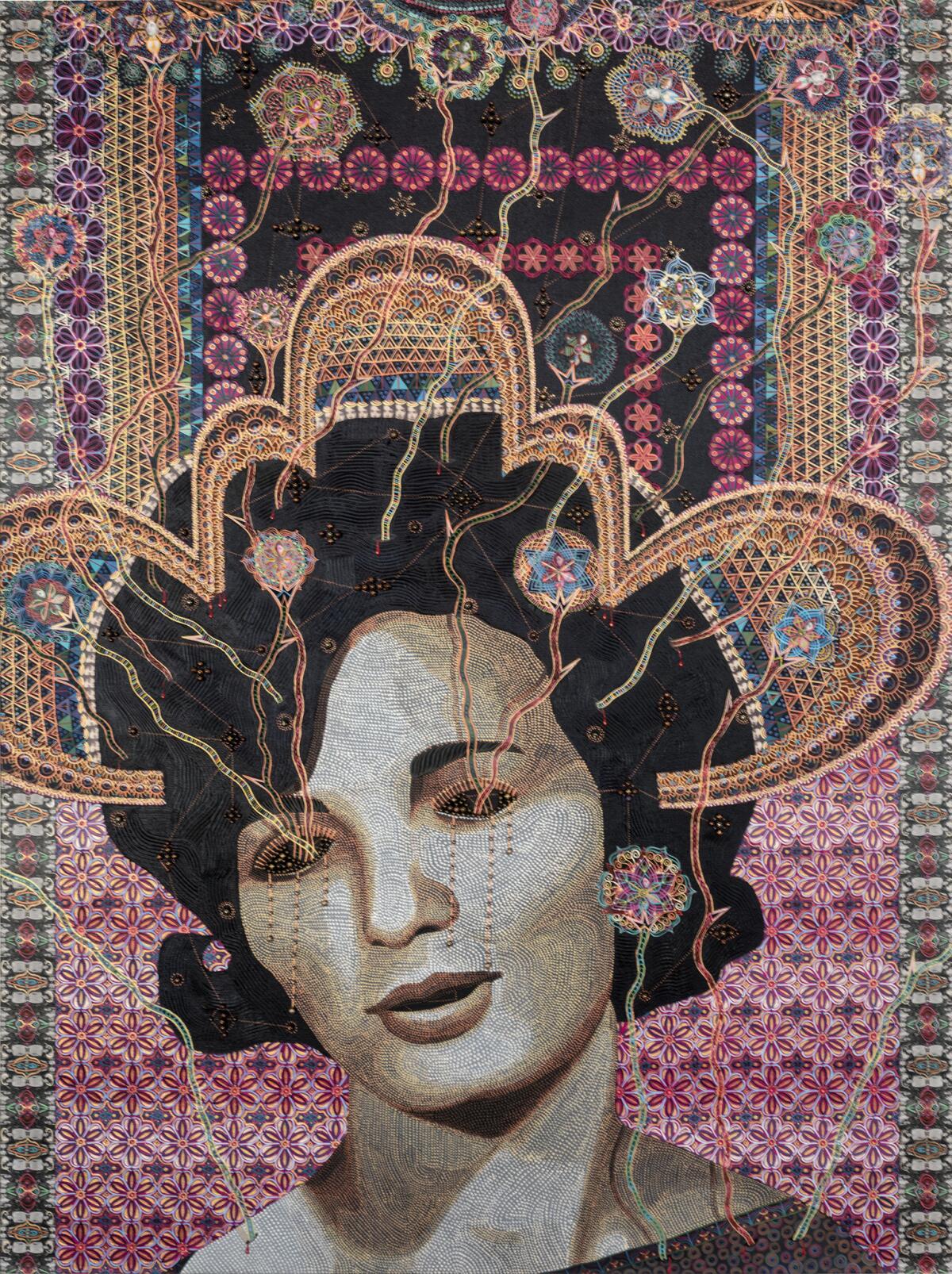

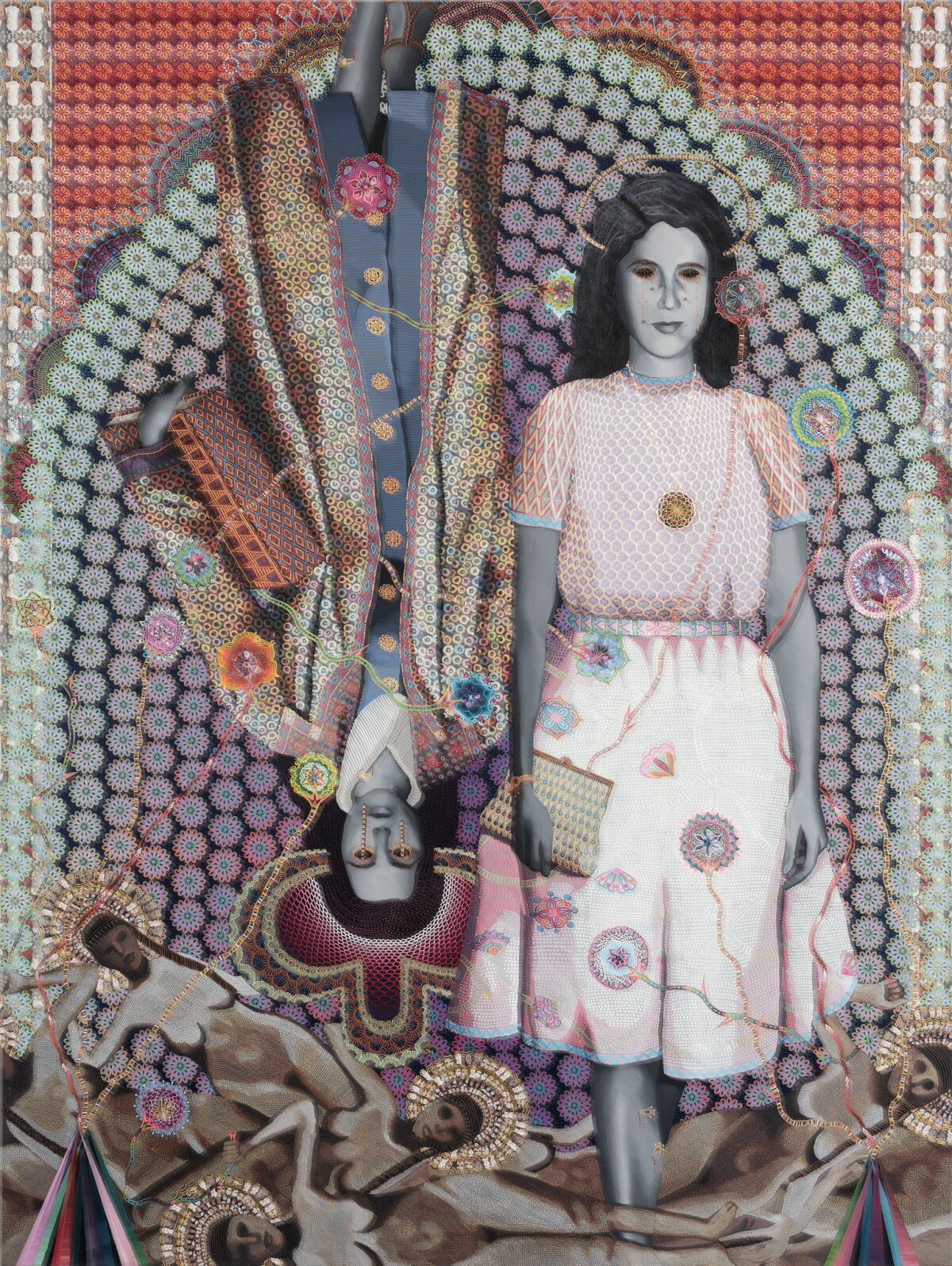

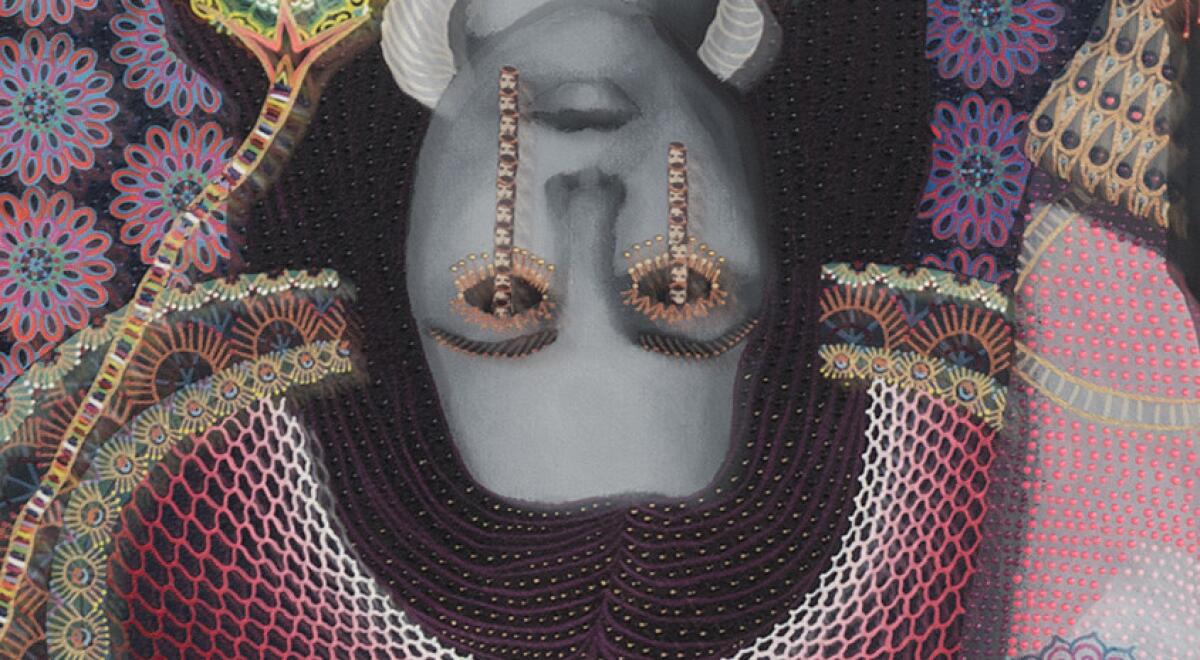

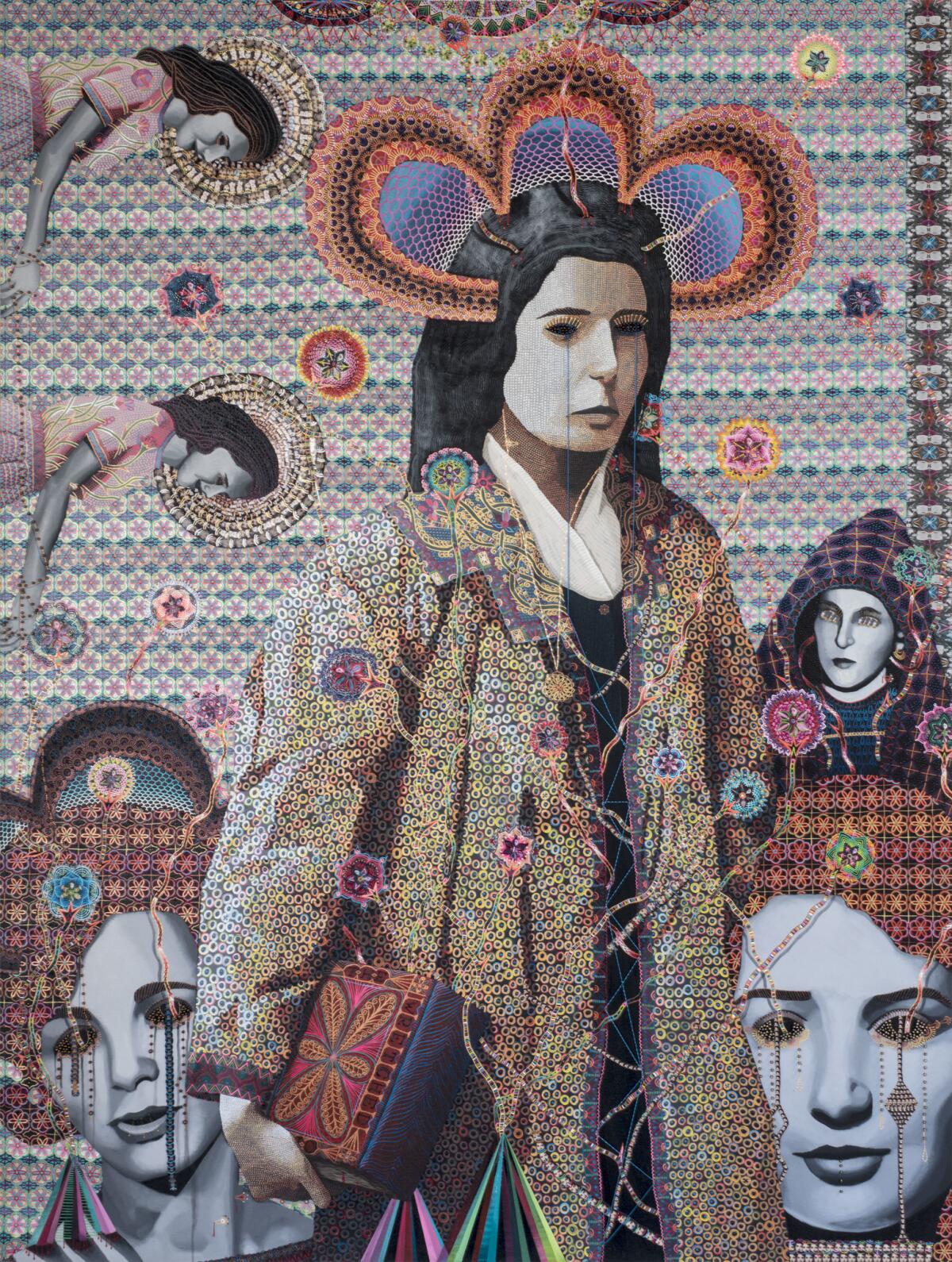

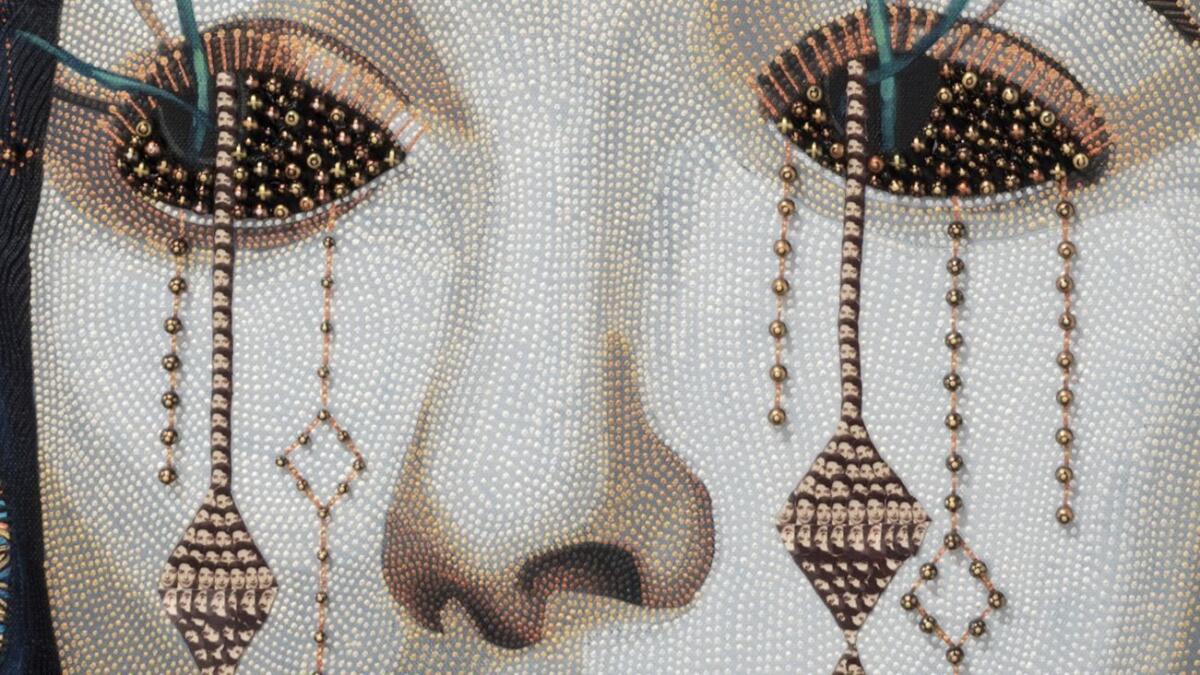

The portraits depict about a dozen women who smuggled in bombs during the Algerian War of Independence 60 years ago, a time when Algerian nationalists were blowing up cafes in a campaign to expel French colonialists from their country.

“The women in the paintings killed people,” Asad Faulwell said, noting the contradictory feelings that the portraits evoke. “They killed civilians in the name of freeing themselves from colonialism. They then went through hell themselves. They were tortured by the French soldiers. They were ostracized by their own countrymen. They are victims, aggressors, killers. My interest was in the moral ambiguity of the whole thing.”

Eight of Faulwell’s new paintings can be seen through July 7 in “Phantom” at Denk gallery in downtown Los Angeles. It’s the artist’s first hometown solo show in 10 years.

Born William Asad Faulwell, the artist grew up thinking that he was an ordinary American kid. In Simi Valley he went to school, hung out with friends and played basketball on the high school team.

At home he spoke Farsi with his maternal grandmother, as well as with his younger brother, Said. With his dad, mom and two of her sisters, who lived nearby and were always around, he spoke English.

“I didn’t think anything of it,” Faulwell said. “There were just two languages that people spoke around me.”

The women in his family had emigrated from Iran in the 1970s and ’80s, just before and after the Islamic Revolution transformed that country from an authoritarian, pro-Western monarchy led by Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi to an authoritarian, anti-Western theocracy led by the Ayatollah Khomeini. Faulwell’s dad, a poet and professor, was born in the United States to parents who traced their roots back to England and Germany.

As a kid, Faulwell didn’t give that dichotomy a second thought.

“The women in my family did things one way, and my dad did things another way,” Faulwell said. “He would tell me one thing, and they would tell me something else. That was just what it was. It was normal.”

Faulwell enrolled in his first year of junior college when 9/11 changed everything.

“Right after that,” he said, “for the first time in my life I started feeling that maybe in other people’s minds I wasn’t an American.”

That confused the 20-year-old. “I felt psychologically and emotionally displaced,” he said. “I thought of myself as an American and suddenly I was seeing people on TV, meeting people in person, who were very much looking at me in a different way. Even though I was born in America, raised in America, American in so many ways.”

The next year, Faulwell transferred from Moorpark College to UC Santa Barbara. The uncertainty he experienced about his ethnic identity did not extend to his artistic identity.

“I went to UCSB knowing I was an artist,” he said. “I knew that since I was 3 or 4.”

His mom and dad tell this story about taking Faulwell to a museum when he was 4. “I started crying,” Faulwell said. “When they asked me what was wrong, I pointed to a painting and sobbed, ‘I want to make that but I don’t know how.’”

Faulwell’s parents encouraged his interest in art. Books about artists were all over the house. Museum visits were common. And on weekends, Faulwell would paint alongside his dad, using his brushes and canvases to make his own paintings.

“My dad was super into [Willem] de Kooning, that whole era of gestural abstraction, the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s.”

When Faulwell went to UCSB, that’s where his head was — American Abstract Expressionism. Then he was introduced to contemporary art. And he was confused by it. He recalled thinking: I don’t know if I like this. This is stuff I don’t understand.

So he studied. And learned. His work was criticized for being dated, for being out of touch with contemporary issues. The pushback was fair. “But,” he said, “I stuck to my guns. I kept making gestural abstract paintings.”

As Faulwell’s understanding of art got more sophisticated, so did his understanding of his identity. He took courses in a newly established Middle Eastern/North African studies program. That deepened the tension he felt as an American of Middle Eastern descent.

ARI'EL STACHEL: Tony winner talks about embracing his Middle Eastern heritage »

To think through the discord, Faulwell returned to his studio, where his paintings got more layered as he struggled to weave what he loved about art together with what he experienced as an American.

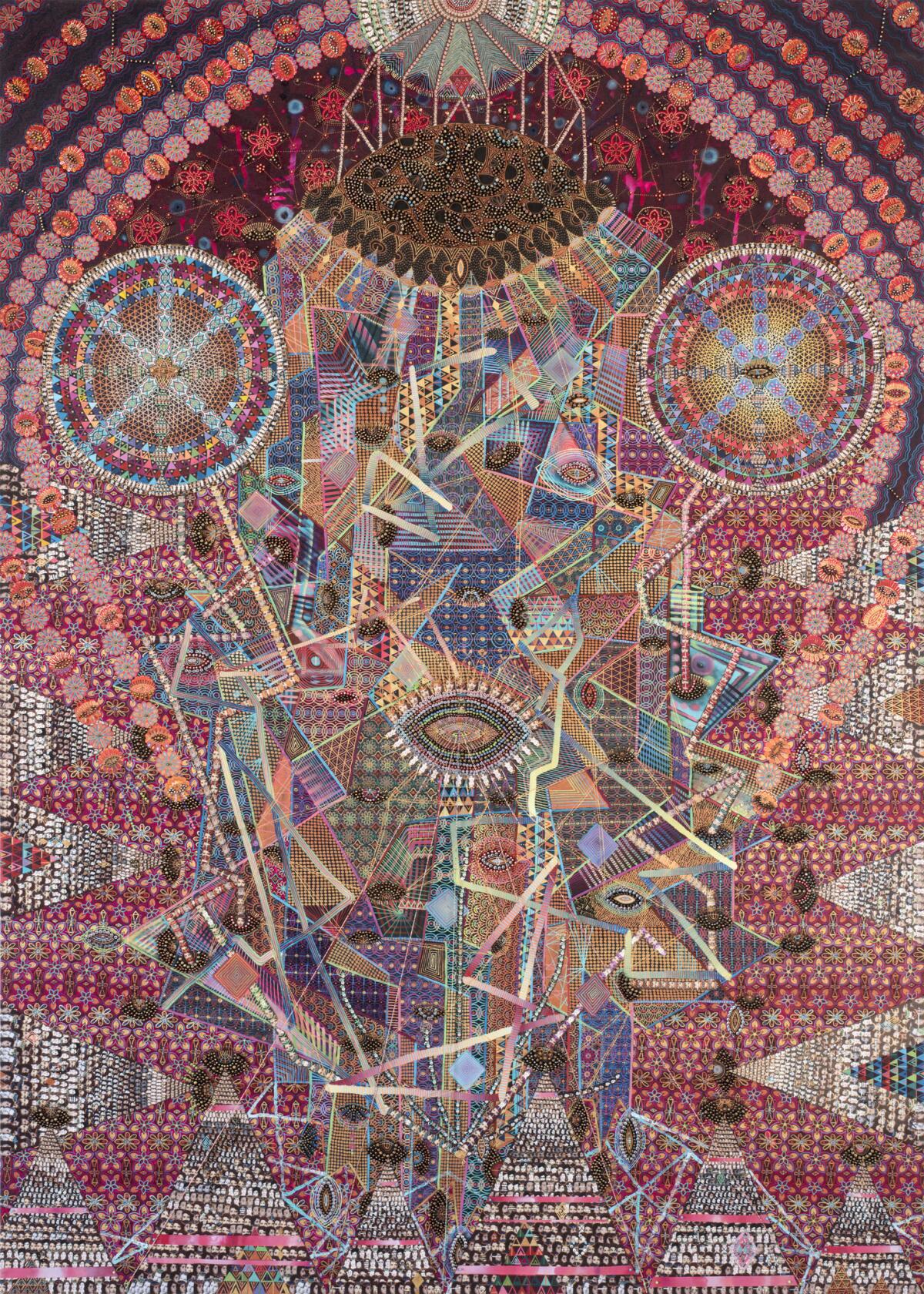

He enrolled in the MFA program at Claremont Graduate University. He began to glue onto his canvases dozens — and then hundreds — of photocopied images of political and religious leaders from the Middle East. Western-style abstraction collided with Middle Eastern history. Gestural Expressionism crashed into Islamic patterning.

“There was an obvious disconnect between the two,” Faulwell said, “but it wasn’t really a problem for me. These were just two things I was interested in. They were important to me. So I thought, why not just smash them together and see what happens?”

A year after he graduated, Faulwell made “Pillars — Iran (1882-1989),” a collaged painting now in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and on view through Sept. 9 in the exhibition “In the Fields of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Iranian Art.”

It was a gateway for his next body of work, which he thought he’d be done with after six or seven paintings.

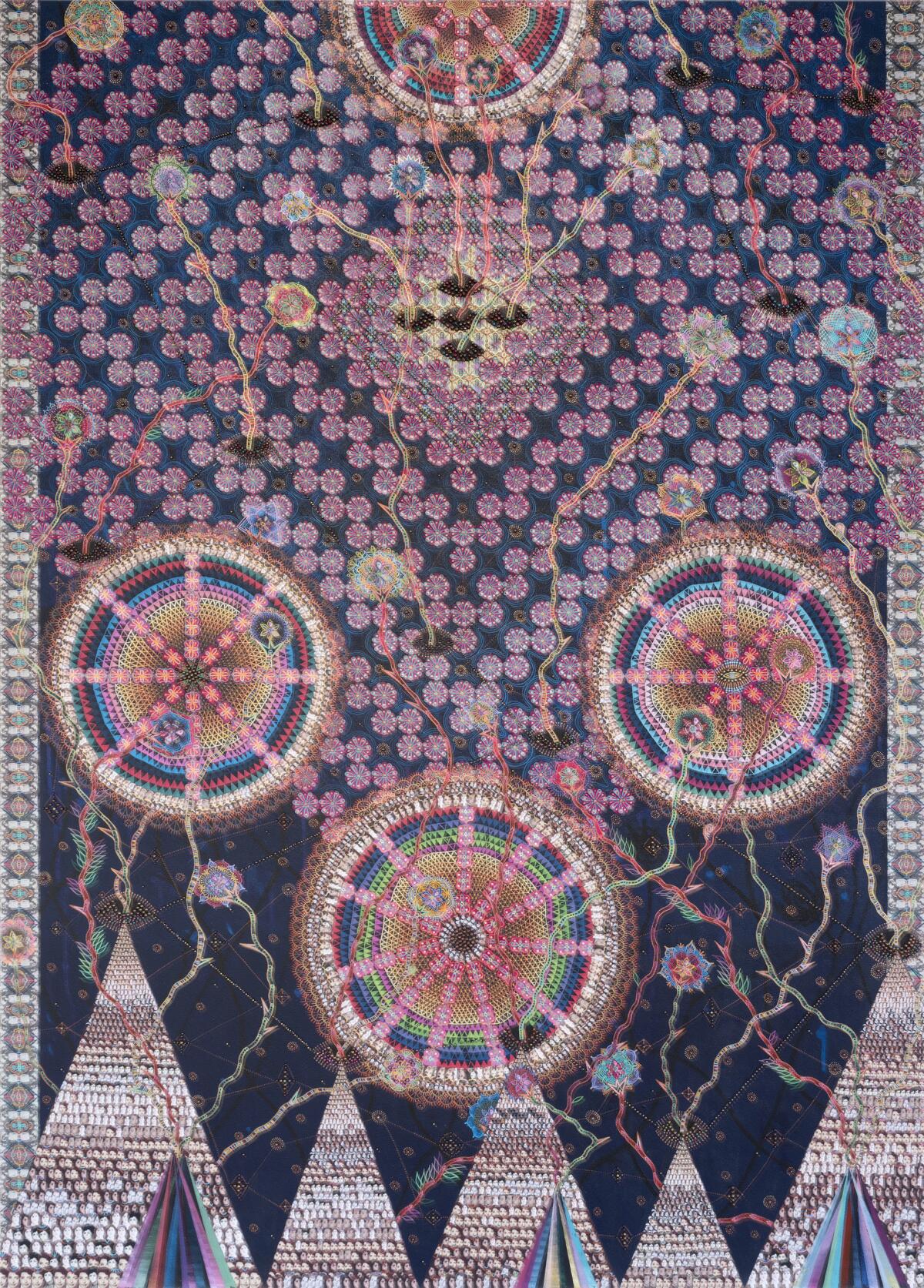

Today, he is still immersed in “Les Femmes d’Alger.” The series currently consists of 85 paintings, some no bigger than a notebook and others measuring more than 15 feet long. All are inspired by film director Gillo Pontecorvo’s “The Battle of Algiers.”

“I was blown away by the movie,” Faulwell said. “It was about all the things I was interested in: history, colonialism, gender, violence, terrorism, freedom, faith.

“In making the first works in the series, I said to myself, ‘OK, I’m not really making work about myself anymore. I’m making work about issues that I’m interested in, issues that exist in the outside world.’”

FAULWELL: In Iranian art show at LACMA, the past wrestles with the present »

The portraits are also landscapes. They include architectural elements, complex geometry and a dazzling palette of glistening gold, luxurious purple, blood red and deep black.

They play off of Eugene Delacroix and Pablo Picasso’s exotic depictions of Algerian women. Faulwell’s intent was to continue that in a different way.

He did. But not without resistance. He said people told him, “You’re not Algerian. You’re not a woman. Why are you making these paintings?”

And his response, which he admits was “maybe a little snarky?”

“If there was an Algerian woman who had made these paintings, then I wouldn’t have done it,” he said. “It’s what I was interested in, and nobody else was making the work. I feel like maybe there is a little bit of a double standard in terms of this. … Writers can write about whatever they want. Journalists can talk about whatever they’re interested in. But an artist has to make work about themselves? That’s limiting. It doesn’t make sense to me.

“I want to talk about things that are much bigger than myself. I try to do that with my paintings.”

Denk, 749 E. Temple St., Los Angeles. Through July 7; closed Sundays and Mondays. (213) 935-8331, www.denkgallery.com

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.