‘Phantasmagoria: Specters of Absence’ at USC’s Fisher Museum of Art

The original phantasmagorias were theatrical thrill rides, equal parts haunted house, communal séance and intense dream. Spectacles that played in Paris, London and beyond beginning about 1800, they used pre-cinematic rear projections, smoke and manipulated lantern slides to create illusions of figures advancing and receding, creatures materializing and dissolving.

Viewers knew what they were getting into -- the shows were entertainment, not scientific efforts to raise the dead -- but the experience tapped into primal human wonder about mortality and its residual traces, the immateriality of the soul and the foggy boundary between absence and presence.

Today we have more ingenious means of conjuring convincing apparitions, but the same basic questions persist: What happens to us after death? How tangible a force is memory? Why do the imagined, the feared and the desired seem at times so real?

“Phantasmagoria: Specters of Absence” at USC’s Fisher Museum of Art presents the work of a dozen international artists who explore such fundamental mysteries using the substances so often associated with them: light, shadow and atmosphere.

Overall, it’s a relatively tight show -- physically involving, emotionally absorbing and conceptually sound. Each artist is represented by a single work, dating from the 1980s to the present, but all have demonstrated over time a broader, deeper engagement with the issues at hand. No artistic integrity was sacrificed in the name of thematic consistency -- and that’s one of the show’s most impressive absences.

The spectacles range in intensity from whispers to roars. One of the quietest works, the Colombian Oscar Muñoz’s “Aliento (Breath),” is also one of the most poignant. Five mirrored discs hang at eye level and bear no image but the viewer’s own reflection until breathed upon. Condensation causes another face to emerge, a small photographic portrait of a deceased man or woman, there only briefly, then once again submerged within the disc’s glossy surface. The faces’ anonymity and the brevity of their appearance act as powerful metaphors for our transient condition, our lives as fleeting as a single breath.

Muñoz’s delicate act of breathing life into vanished souls competes with the foggy extravaganza of a neighboring installation. Danish artist Jeppe Hein’s “Smoking Bench” blankets you with vaporous plumes when you sit on it. A nearby mirror allows you the pleasure of watching yourself momentarily vanish, a gimmicky but amusing smoke-and-mirrors illusion.

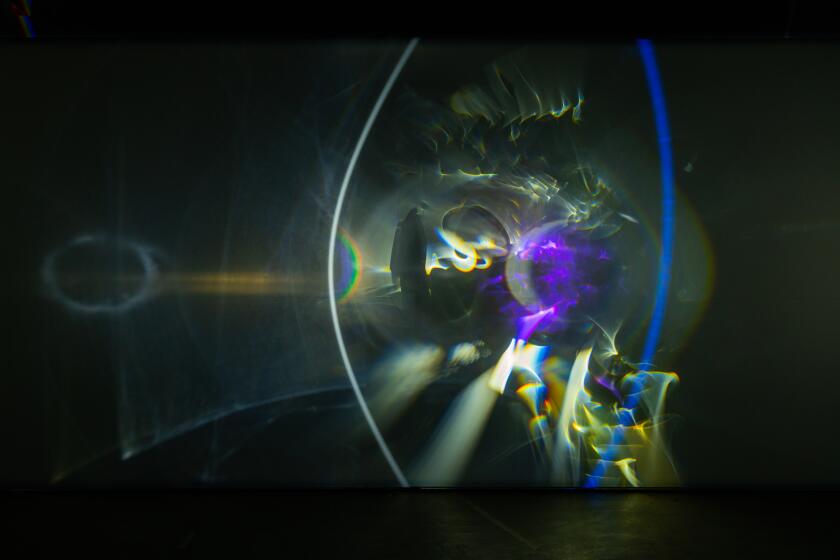

Vapors are central to several other works in the show. Five portable humidifiers in Teresa Margolles’ “Aire (Air)” emit gentle streams of air moistened, in part, by water that was used to clean corpses in a Mexican morgue. The notion is stirring, but the piece is otherwise mute. In “Experiencing Cinema,” a better use of atmospherics, Brazilian Rosângela Rennó revives an early 19th century phantasmagoria practice of projecting still pictures onto veils of smoke. Photographs, gathered from found family albums, cohere briefly on the smoke screen; then both image and screen dissipate, mortality again provocatively aligned with ephemerality.

Atmosphere is an active, even aggressive force in Laurent Grasso’s untitled three-minute film of a roiling cloud tumbling through the streets of Paris. The foggy mass pushes forward like a biblical pillar of smoke, endowed with a will. It fills every street, enveloping cars in its path, persisting with a constant low rumble. The image is mesmerizing and beautiful, even as it recalls 9/11’s death-infused clouds of dust.

William Kentridge’s short film, “Shadow Procession,” similarly fuses the epic with the historically specific. Silhouetted cut paper figures parade across the screen: workers, scavengers and fighters, the injured and maimed, mothers with children, a man hanged, another being beaten, the victorious and the defeated. The displacement that comes from violent upheaval, as in South Africa in the ‘90s, when this work was made, fuels this dark parable of persistence.

The evocative power of shadows and reflections dominates the remaining works. Christian Boltanski’s orbiting dancer, seen in shadow through a partly opened door, is mildly intriguing for its calculated elusiveness. In Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s installation, the movement of viewers triggers the brightness of a row of low-hanging incandescent bulbs, creating a play of overlapping shadows on the opposite wall, but the effort amounts to little. Regina Silveira’s perspectively distorted shadow of a reader (in vinyl, adhered to wall and floor) holding an actual book, feels slight, as if it ought to be part of a larger installation.

Viewers become animators in French artist Michel Delacroix’s installation. His four portraits, on mirrored plates covered with a thin layer of water, are mounted on tall, slim-legged tripods so the faces cast a ghoulish reflection on the wall behind them. As you walk on the wooden platform beneath them, the features warp further, rippling and quavering like ghosts released by permission of your movement.

Jim Campbell layers a photogravure over a grid of programmed LED lights to create an image of shadowy figures moving up and down the steps of the New York Public Library. Human presence appears as shifting, translucent gray washes across the fixed stone edifice, resulting in a lovely meditation on time, endurance and transience.

Danish artist Julie Nord introduces a welcome note of play, fittingly tinged with the ominous. Her wall drawing illustrates a sequence of hand positions and their corresponding shadows of dogs and rabbits. In the final frame, the one-to-one relationship breaks down and the dark demons of the unconscious take over, unleashing shadows of a fire-breathing, fork-tongued dragon and a vaguely human, clawed beast.

This is the final stop for the exhibition, curated by José Roca for the Museo de Arte del Banco de la República in Bogotá, Colombia, and Independent Curators International, based in New York. It may not consistently get under the skin, but it regularly sends a tingle across it.

Ollman is a freelance writer.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.