Leaning into the future: Rem Koolhaas’ OMA releases first look of Wilshire Boulevard Temple event space

“We have to honor the past and speak to the future,” declares Wilshire Boulevard Temple’s senior Rabbi Steven Leder. And he says that’s exactly what a new event space designed by Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture will do for Los Angeles’ oldest Jewish congregation.

The first rendering of the 55,000-square-foot Audrey Irmas Pavilion, which will stand east of the historic temple, reveals a trapezoidal form that leans away from the temple and toward Wilshire Boulevard.

For the record:

7:55 a.m. March 30, 2018An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated Shohei Shigematsu’s title at OMA. He is partner.

“The whole form is generated from a respect to the existing structure,” says OMA partner Shohei Shigematsu, who is the project’s lead designer. “We moved it away from the temple and the school that is there. It was about creating space around the historical building.”

The original temple, now on the National Register of Historic Places, was designed in a Byzantine Revival style and completed in 1929. (It was recently the recipient of a $47.5-million overhaul, finished in 2013).

OMA’s design for the pavilion avoids copycat Byzantine forms in favor of fluid lines that gently echo aspects of the historic building.

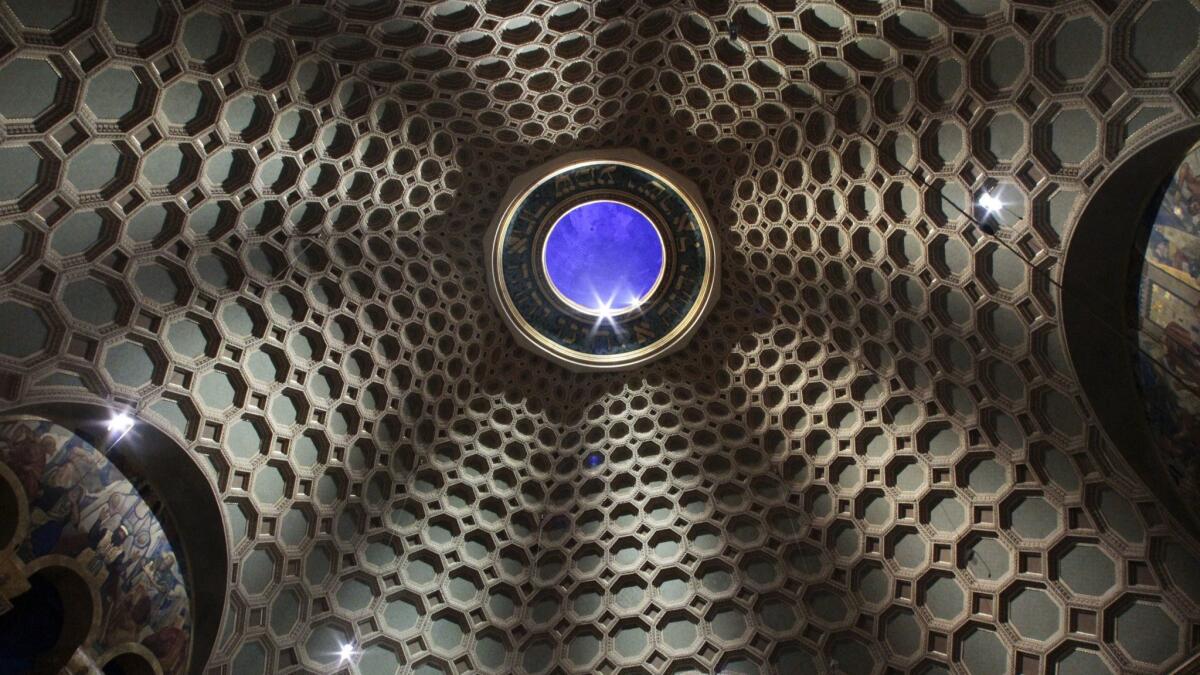

An arched entrance in the new building evokes the shape of the old temple’s brilliant gold and green dome (funded in the 1920s by movie tycoon Irving Thalberg). Likewise, the proposed building’s geometric skin, which features a hexagonal pattern bearing rectangular windows, is inspired by a similar pattern inside the dome.

“There are relationships we carefully considered,” Shigematsu says via telephone from OMA’s New York offices. “We wanted it to have some kind of relationship to the dome. The arch is on the ground but it resonates with the dome on the temple.”

“The inside of the dome is just staggeringly beautiful,” Leder says. “Like all great cathedral architecture it creates two paradoxical feelings: It’s about feeling both great and small at one and the same time. Rem’s building does this also.”

It’s about feeling both great and small at one and the same time.

— Steven Leder, senior rabbi, Wilshire Boulevard Temple

The marquee space within the new four-story building will be a ground-floor banquet hall with a 36-foot ceiling. A third-floor multipurpose room will feature a glass wall that fully retracts, creating a broad outdoor patio on the building’s western side.

“That’s the second-biggest flexible meeting space in the building,” Shigematsu says. “The void frames the stained-glass window of the temple. It’s always about the visual relationship to the existing temple, paying respect to the building.”

In addition to a commercial kitchen, meeting and conference spaces for the congregation’s social and charitable projects, and social services facilities, the building will contain a rooftop space with a sunken garden conceived by L.A.-based landscape designer Mia Lehrer.

“We don’t quite have a rooftop culture in Los Angeles, but it’s coming,” Leder says.

“It’s the inside-outside connection,” Shigematsu says. “It has a great view to the Hollywood sign and a great view of Koreatown. We imagine it will become like an elevated park.”

Leder says that with $55 million of the estimated $75 million cost already raised, the synagogue is well on its way to making construction of the Audrey Irmas Pavilion a reality. A majority of those funds came from Irmas, who sold a 1968 “blackboard” painting by Cy Twombly at auction in 2015 and donated $30 million from that sale for the pavilion.

Leder says that, “optimistically,” the temple could break ground by fall, with completion scheduled for 2020.

The pavilion would be the first cultural building in Los Angeles by the Pritzker Prize-winning firm, whose only other built project in the city is a Prada boutique in Beverly Hills. (His firm, however, does have other L.A. designs in the works: a mixed-used project in Santa Monica and the design for the First and Broadway Civic Center Park in downtown.)

The design, the rabbi says, is “something really special” — a structure that can serve as an architectural tent-pole in the heart of the city.

Of the contemporary nature of the design, Leder says: “We’re all in.

“It’s as our ancestors did when they built the great sanctuary,” he adds. “People who are critical of the boldness of the vision, I say that this is probably the same discussion that happened when the great sanctuary was built in 1929.”

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

Wilshire temple celebrates a revival

L.A. arts patron selling Cy Twombly painting to fund synagogue events center

Documentary-maker rediscovers Judaism, family, self

Why so many Mexicans revile the Colonial Californiano architectural hybrid that spread from SoCal

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.