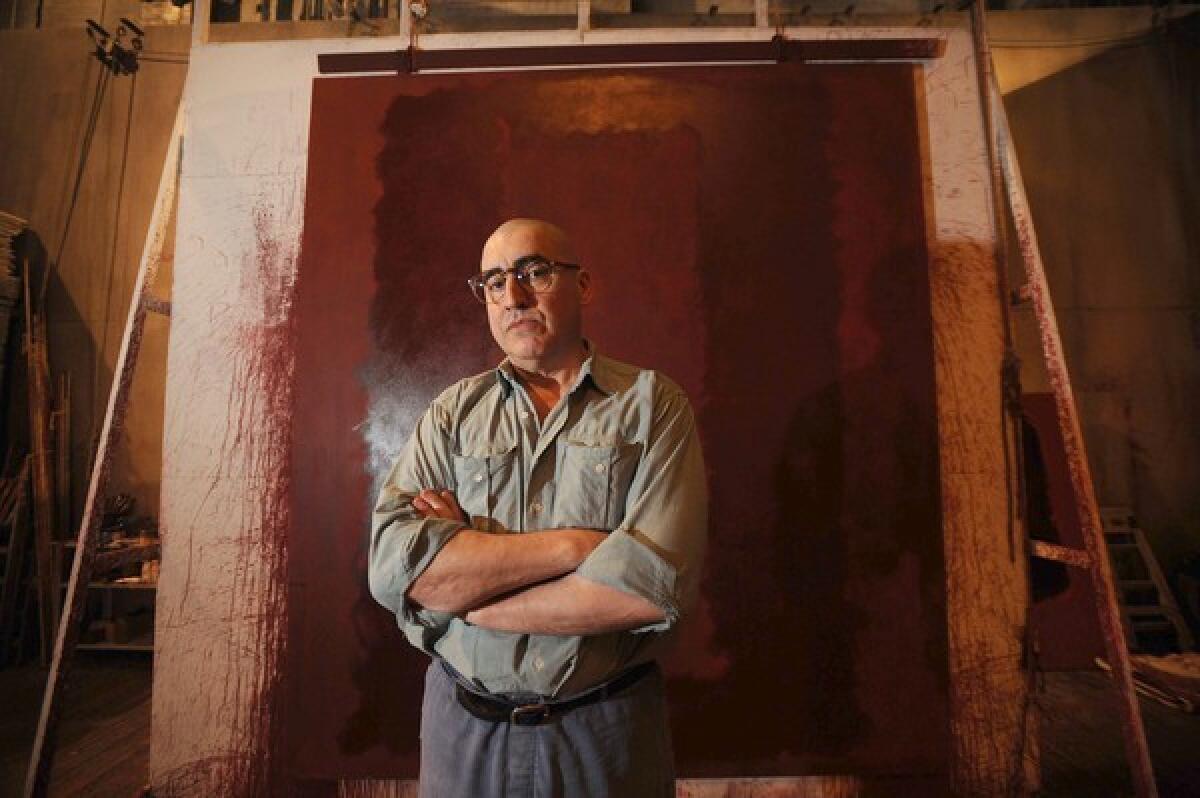

Alfred Molina paints the town ‘Red’

When actor Alfred Molina got a call that Michael Grandage, artistic director of London’s high-profile Donmar Warehouse, wanted to meet with him, he relished a session of gossip about London theater.

But Grandage had a different agenda. Toward the end of their chat, the director slid a FedEx envelope across the table.

“Is this what I think it is?” asked Molina. “It looks suspiciously like a play.”

Grandage told him about the play and the part, left him the script and Molina went off to a restaurant and started reading.

“By Page 21, I knew I had to do it,” Molina recalls. “I often tell people that when you read a play, the moment when you know you have to do it is not a punching-the-air moment. It’s actually a sinking feeling because all your options disappear. Everything narrows down to this one thing you know you have to do.”

The role was Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko, the central figure in John Logan’s new drama, “Red.” The 90-minute play is set in Rothko’s New York studio in 1958 as the painter works on a series of murals commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant in the city’s iconic Seagram Building.

Taking on a commission he didn’t need and a new assistant he did, Rothko rails against an art world that is changing -- and a young man who embraces the change.

“It was telling a very real, very powerful story about an intelligent, troubled and conflicted man,” says Molina. “You think, ‘Wow, Rothko is demanding, difficult and a bully,’ but at the same time you can’t stop listening to him.”

London transfer

“Red” debuted in December at the Donmar, directed by Grandage and costarring Eddie Redmayne as assistant Ken. His head shaved, his demeanor fierce, Molina inhabits Logan’s isolated, isolating protagonist, raging at Redmayne’s Ken but also at himself. The play and its actors fared well with London critics and audiences and, following the path of earlier transfers of the Grandage-directed “Frost/Nixon” and “Hamlet” with Jude Law, opens on Broadway April 1.

“The spirit is larger because we’re now in an 800-seat theater [the Donmar has 250 seats], and I hasten to add that Alfred Molina is even better on Broadway, because he’s been unleashed,” says Logan, screenwriter of “Sweeney Todd,” “The Aviator” and “Gladiator.” “He has a greater animal freedom, and he is now absolutely ferocious.”

Onstage as Rothko, that is. Molina has a short break at home in Los Angeles between his London performance and Broadway, and over coffee in a Hollywood diner he is much closer to his affable Englishman in the film “An Education.”

Though he is imposing at 6 feet, 2 inches, beneath his bushy eyebrows the deep brown eyes are friendly, the body language relaxed, the manner charming.

Few actors appear so different so often. Onscreen, for instance, he’s appeared as a Spanish bishop in “The Da Vinci Code,” a British soldier in “The Little Traitor,” a Mexican muralist in “Frida,” a French mayor in “Chocolat,” a drug lord in “Boogie Nights” and an Iranian doctor in “Not Without My Daughter.”

His stage work is also eclectic: He was nominated for a 2004 Tony Award for playing the Russian Jewish milkman, Tevye, in “Fiddler on the Roof” and again in 1998 for his performance as a worried stationer in Yasmina Reza’s “Art.”

“Red” follows his well-received performance in “An Education,” in which he played the ambitious British father of a bright teenage girl ( Carey Mulligan) whose judgment is clouded by her smooth-talking older suitor.

“You always feel there’s something more that he doesn’t reveal,” says Lone Scherfig, director of “An Education.” “He’s like a Ferrari: You can press the gas pedal more and it can go much faster, but there’s no need.”

Writer Lynn Barber, whose memoir inspired “An Education,” has written that she found Molina “positively heart-rending” as her father, and Scherfig confides “he understood the character better than I did. It was under his skin. He knew that London in the late ‘50s.”

Varied upbringing

Molina, 56, was, after all, born and raised in ‘50s working-class London himself. His Spanish father was a waiter and his Italian mother a chambermaid who met in London while working at the same hotel. Their home was in Notting Hill, before it was gentrified, and which Molina describes as a lively, mixed neighborhood full of West Indian, Irish, Polish, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese families.

He learned both Spanish and Italian at home, sharing his parents’ ability to pick up languages quickly, and pegs his ear for accents to having been brought up with a range of them at home and at school.

“I didn’t look or sound English growing up, and I was playing Eastern European thugs when at drama school,” says Molina, who studied acting at Guildhall School of Music and Drama. “I was the go-to-guy for foreign parts, which is fine because I think I carved out quite a nice little niche for myself.”

He had worked at the Donmar briefly in 1977 for the Royal Shakespeare Company and was back in 1982 for the musical “Destry Rides Again,” where he met his wife, the actress Jill Gascoine.

Director Grandage, who had seen his work as far back as “Destry Rides Again,” says: “There are only a few actors in the world who could take on what John Logan’s Rothko requires. Rothko in this production is an egotistical, vain, larger-than-life character, and to get an actor to agree to meet that head-on and not make apologies requires an actor with very little vanity. I wanted somebody like Lear in the storm but also capable of showing us the very fine delicate internal mechanism of the man as well.”

Avid researcher

Molina knew a little about Rothko and had seen the Seagram murals at London’s Tate, where they landed when Rothko returned his $35,000 commission and kept the paintings.

But he did considerable research on the artist, adding that “once a character inhabits you, you become very protective. You feel ownership the way a parent might feel ownership of a child. I find myself absolutely obsessed with not misrepresenting the character. I want to make sure I’m smoking the right cigarettes and drinking the right brand of whiskey.”

Playing Mexican muralist Diego Rivera in “Frida,” he was sent to classes to learn to hold a paintbrush correctly and says for “Red” too artists offered tips. “But once you have a vague idea of the mechanics, you make it your own. It’s not about making it real or realistic but about making it authentic.”

Rothko had assistants who helped him stretch the canvases and build frames. Molina adds that “The play is about the making of art, and the practical, physical labor that’s involved. We also prime a canvas, which I think is one of the most exciting things I’ve ever done onstage.”

In “Red,” after a blistering attack on art collectors, Rothko says simply, “Okey-dokey, let’s prime the canvas,” and the two men set to work on a 6-foot-square blank canvas. With Molina working the top half and Redmayne the bottom, they madly apply the dark-plum priming liquid that soon covers them as much as the canvas.

Infamous as the multi-tentacled “Doc Ock” of “ Spider-Man 2,” Molina will soon slip into new movie guises. Due out May 28 is “Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time” starring Jake Gyllenhaal, in which Molina plays “a lovable rogue,” and coming July 16 is “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” in which Molina’s self-described “out and out villain” takes on sorcerer Nicolas Cage and his apprentice Jay Baruchel.

Abstract Expressionist, lovable rogue or out-and-out villain -- Molina doesn’t demean any of it. “Yes, I’ve played a lot of villains, but I don’t knock it. The villains have put two kids through college. People ask, ‘Are you worried your legacy is as the guy who played Doc Ock?’ I say, ‘No -- that makes me part of film history.’ ”

The actor seems similarly clear about his portrayal of Rothko. “While I’m not sure I could have survived an evening with him, I have nothing but admiration for him,” says Molina.

“At some level you do fall in love with your characters, but part of the joy of understanding and playing these parts is to not allow the bad stuff to disappear. If audiences dislike my character, that’s fine with me. I want them to go away thinking, ‘Wow, I didn’t know that about Rothko.’ ”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.