‘Wild Child: And Other Stories’ by T.C. Boyle

Wild Child

And Other Stories

T. C. Boyle

Viking: 320 pp., $25.95

In “Thirteen Hundred Rats,” one of the 14 stories in the latest collection from the seemingly inexhaustible T.C. Boyle, a recent widower finds himself the owner of a python. He’s allergic to cats and dogs, those more cuddly and condoned companions of the grief-stricken. But then something really unexpected happens. The white rat he’s purchased for his new pet’s sustenance proves unusually adept at eluding its fangs. The rodent’s improbable athletic performance elicits astonishment, sympathy and, eventually, love. The widower spares the rat -- supple as suede, a tiny creature quivering with hope and optimism -- and decides to give the soulless python the heave-ho. “The situation was novel,” Boyle’s narrator declares, “to say the least.”

Throughout this dazzling collection -- which veers from California to France, from the present to the past -- Boyle’s stories have a habit of gazing back upon themselves with eyebrows cocked in wonder. And with good reason. Boyle is a master who has earned the right to be giddy about his bravura creations, which often turn on such pungent moments. Take for instance the mother of a Venezuelan relief pitcher in “The Unlucky Mother of Aquiles Maldonado.” When she’s spirited off by a band of grubby guerrillas and secreted in a jungle compound (her son’s lucrative career in the States and his Hummer make their family a conspicuous target for kidnapping), she merely goes about doing what she does best: making arepas and taking care of boys. In the end, Aquiles’ multimillion-dollar arm comes in handy during an explosive rescue attempt that, like so much of Boyle’s work, good-naturedly toys with the limits of credulity.

The profane, Glock 9-toting courier in “La Conchita” also finds himself in a particularly sticky situation: caught in a mudslide on Pacific Coast Highway while shuttling a human liver (packed in ice inside a Bud Lite Fun-in-the-Sun cooler) to a would-be transplant recipient and being forced to confront his inner Good Samaritan when mudslide victims beg him to pick up a shovel.

Such potent, indelible glimpses of California -- loaded to the gills with dark humor, natural disasters and brushes with Botox -- abound throughout “Wild Child.” The 13-year-old brat at the heart of “Ash Monday” is perpetually at war with his Japanese American neighbor in a classic struggle of white trash intransigence versus immigrant striving, one that involves some potentially deadly elements: a backyard grill, flammable liquids and a strong Santa Ana wind. As in much of the Boyle oeuvre (his much-anticipated next novel is purportedly about species eradication), Armageddon is never far off, and the angry threats of the natural world have a way of becoming palpably, alarmingly real, as they do here: “The first premonitory crackle in the leaves gathered like a skirt at the ankles of the bamboo.”

Other California apocalypses are quieter, emotional affairs that build up and up, only to send the fault lines in relationships buckling wide open. Angelle, the beset tweener girl of “Balto” -- one of the most sure-handed stories here -- has been given the creepy assignment of telling one of those “little fibs that don’t really hurt anybody” in a courtroom to exonerate her feckless father, who allowed her to take the wheel of the family car when he was too tipsy to drive. You watch Angelle, page after page, waiting for the moment when she will explode.

In “Admiral,” a rich, childless couple reeking of entitlement hires back Nisha, their former housekeeper, so she may care for the clone of their late, beloved Afghan hound, just as she did the original pet. It’s an astonishing meditation on that peculiarly American habit of all-out war against mortality, a puckish take on nature and nurture gone haywire. That story’s bookend is “Bulletproof,” which tells of a community riled up over the disclaimer sticker that a local band of creationist zealots have forced onto a ninth-grade biology textbook. Cal, a divorced guy enraged by the creationists’ “hope masquerading as certainty, desperation plucking at your sleeve, plucking, always plucking and pushing,” nevertheless becomes curiously attracted to the hot divorcée behind the effort and amazed at her pious daughter’s insights into the natural world.

Like so many of these stories, “Bulletproof” has intricacies of plot and character that suggest a full-on Boyle novel in miniature, all zooming story lines and eye-saturating color. Of course, there will be some who find Boyle’s palette garish, his characters cartoonish, his narrative fireworks mere antics of a strutting virtuoso. But Boyle is the closest thing we have to a modern-day Washington Irving, that American storyteller par excellence who found a perfect balance between art and pop, and who lived and worked not far from Boyle’s own boyhood home along the Hudson River.

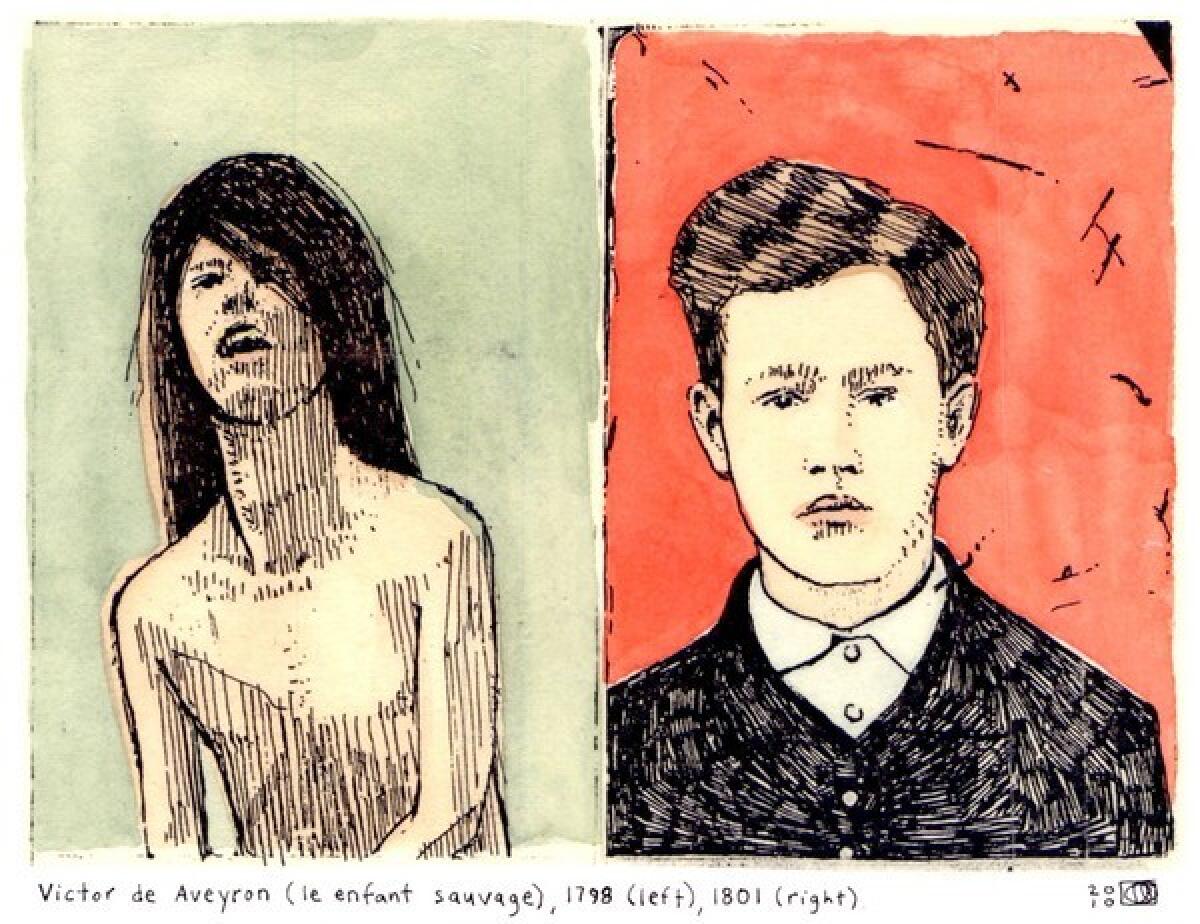

“Wild Child’s” finest entry is perhaps the title story, a novella, really, originally published in McSweeney’s in 2004. Here, Boyle’s runaway-train imagination is tethered to facts every bit as out-there as his own fiction: It’s an examination of the life of the famed feral child Victor of Aveyron, one of the Enlightenment’s oddest celebrities and the subject of François Truffaut’s 1970 film, “L’Enfant Sauvage.” As we watch Victor -- part boy, part animal, part pet -- unself-consciously munch on rodents, reluctantly take to the idea of clothes and hot baths, and struggle to get a handle on the word “lait,” Boyle toys with some of his favorite themes: the shadowy recesses of history, humans and their mysterious drives, the delicate point where self-delusion (here in the form of Victor’s devoted teacher, Itard) teeters between good and ill. In the end, Victor’s wildness will not be expunged: “[T]he orphanage could hardly be expected to contain him.”

The same could be said of Boyle, that literary wild child whose flights of narrative fancy refuse to be domesticated.

Rozzo is a critic in Brooklyn, N.Y.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.