Book review: ‘Here’ by Wislawa Szymborska, translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak

Here

New Poems

Wislawa Szymborska, translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: 86 pp., $22

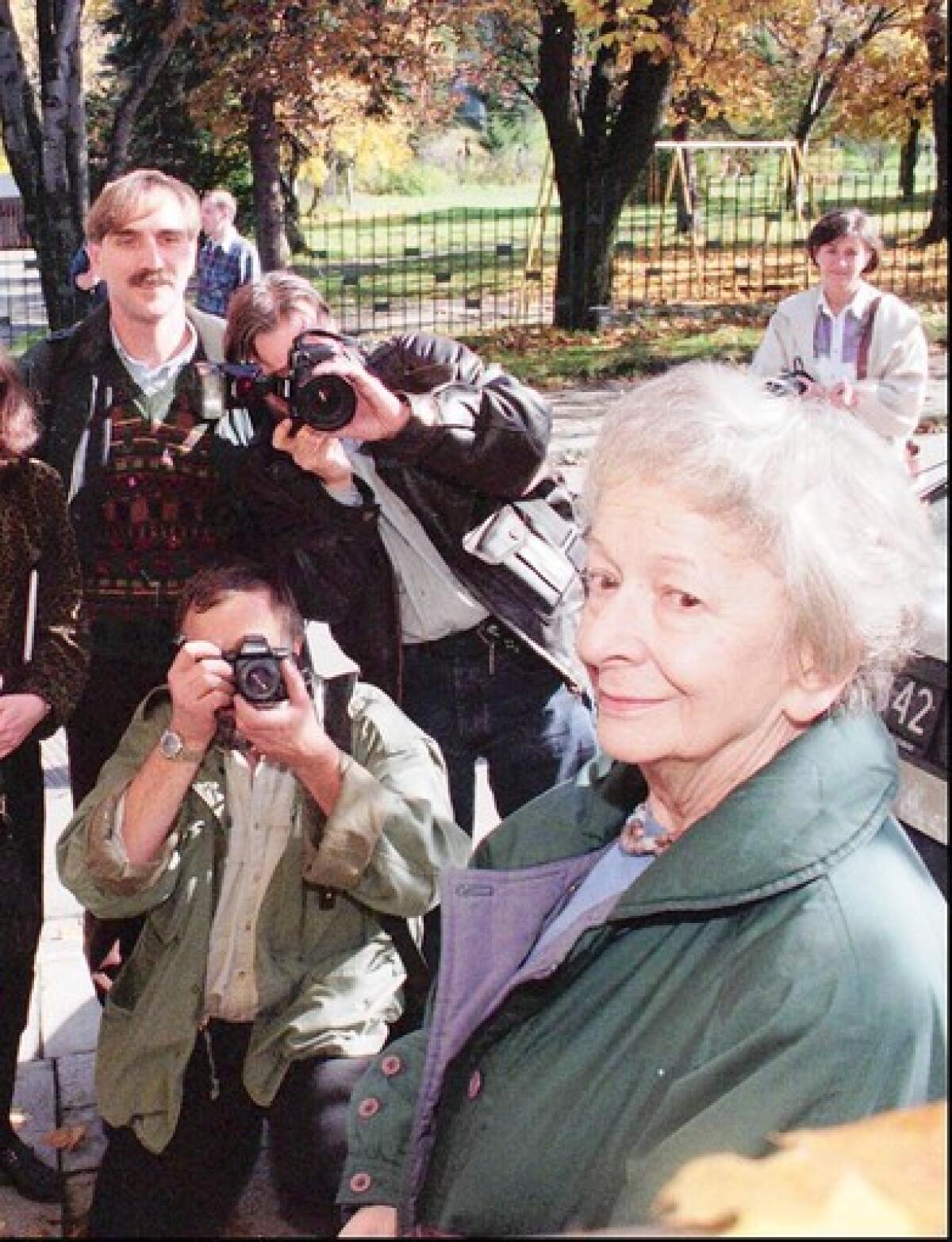

Winners of the Nobel Prize in literature often experience the loss of obscurity that accompanies the honor as a kind of curse. Their work becomes unassailable, marmoreal: It is “official,” static, statuesque. This is a complicated irony in the case of the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska, who was awarded the prize in 1996. Szymborska, in her younger years a supporter of Stalin and an author whose poems one critic called “agitation-propaganda in a chamber-music manner,” has spent her mature career writing against authority. This is not to say that her poems are political — only that they make an argument for the centrality of the seemingly inconsequential.

Szymborska is a poet of looking, and looking askance. Her voice, expressed through simple, wry declarations and observations — tactfully and succinctly translated into English for many years by the team of Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak — is defined by the perspective she adopts more than by flourishes of language, form or syntax. In her new collection, “Here,” published in a bilingual edition, Szymborska’s vision is bifocal. “Teenager” has the poet imagining an encounter with her younger self, a tall, smooth-skinned stranger. It posits two simultaneous realities, that of the girl who “knows next to nothing — / but with a doggedness deserving better causes” and that of the adult who knows “much more — / but not for sure.” Elsewhere, memory is personified as one who “thrusts old letters, snapshots at me eagerly” and, unhealthily, “wants me to live only for her and with her./ Ideally in a dark, locked room.”

There is an easy charm to Szymborska’s small but expansive poems. But it is possible for insouciance to be irritating. “Metaphysics,” a big title for a poem of 12 short lines, dwindles to an indisputable but less than revelatory point: that it is “an unquestionable fact,/ a fact for ever and ever,/ for the whole cosmos, as it is and will be,/ that something really was/ until it was gone,/ even the fact/ that today you had a side of fries.” Szymborska, intending, perhaps, to locate the profound in the trivial, here succeeds in passing off the trivial as profound. So deliberate a lack of style is its own form of pretension. Not to mention that it feels a bit lazy coming from a writer of Szymborska’s acuity and perceptiveness. “Here” is a short collection — 27 poems — but not necessarily a tight one.

The poems are strongest when they contemplate imagined futures and counter factual pasts. What would have happened if the poet’s mother had married “Mr. Zbigniew B. from Zdunska Wola,” and her father had married “Miss Jadwiga R. from Zakopane”? Szymborska asks playfully in “Absence.” Perhaps there would have been two girls, “not kindred spirits,/ no affinities,/ at opposite ends of class photos,” and, in the spot the poet would have occupied, a gap. “The Day After — Without Us,” a poem whose irony derives from its title, delivers a deadpan weather report (“The morning is expected to be cool and foggy./ Rainclouds/ will move in from the west./ Poor visibility./ Slick highways.) before concluding that on the day after that, despite a sunny forecast, “those still living/ should bring umbrellas.”

Often, Szymborska’s poems re-create the fleeting instant when disbelief is in suspension and an act of the imagination can take place. “In fact every poem/ might be called ‘Moment,’” she writes. This makes for a pleasurable, even relaxing reading experience, though often the implications are dark. A poem such as “Highway Accident” takes as its subject the lag between a tragedy and its impact; “Identification” pushes the idea further, in the voice of a woman denying to herself that her husband has died in a plane crash: “They gave me some pills so I wouldn’t fall apart./ Then they showed me I don’t know who./ All black, burned except one hand.” But “Greek Statue,” a piece that, in gently touching on the great lyric themes of time, death and art-making, shows Szymborska at her subtle best, finds the perfect metaphor for that pause. At once fleeting and frozen, the statue’s torso, she writes, “lingers/ and it’s like a breath held with great effort,/ since now it must/ draw/ to itself/ all the grace and gravity/ of what was lost.” Her most skillful poems — think of them as broken friezes or bits that suggest rather than encompass the whole — do this same work.

Goodyear is a staff writer for the New Yorker and the author of the poetry collection “Honey and Junk.” Her second collection of poems is forthcoming from W.W. Norton in 2012.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.