With ‘Moonlight Sonata,’ Irene Taylor Brodsky returns to her family and film roots

In 2007, Irene Taylor Brodsky’s “Hear and Now” won Sundance’s documentary audience award. On Monday, a dozen years later, she returned to the festival with “Moonlight Sonata: Deafness in Three Movements,” a film she insisted she was never going to make.

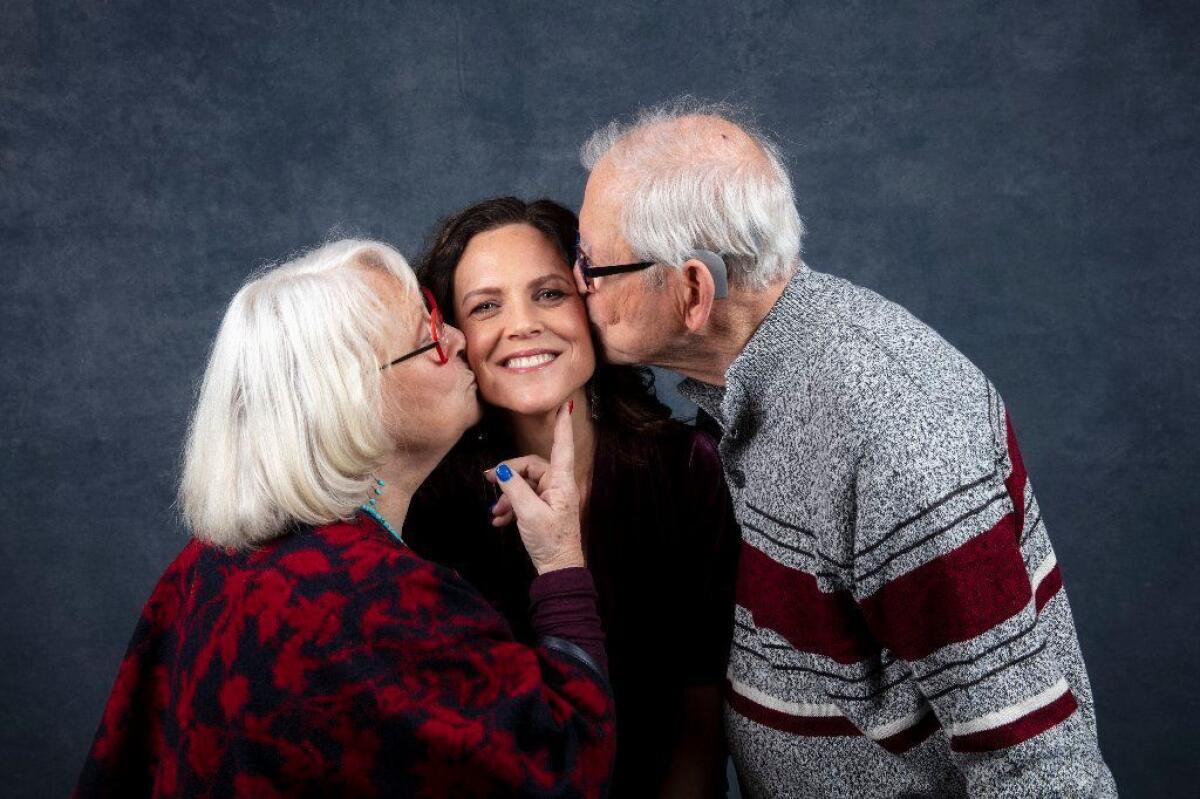

“Hear and Now” told the powerful story of Brodsky’s deaf parents and the consequences of their complex decision, at age 65, to have cochlear implants that restored their hearing. It was a Peabody Award winner and a success at film festivals from Korea and Moscow to Abu Dhabi.

“That response was incredibly validating,” Brodsky says now, “not just for me but for my mother and father.”

But as someone who’d been a producer at “CBS Sunday Morning” and had made docs before Sundance (and has since won an Emmy and been Oscar-nominated), the filmmaker felt telling personal stories was behind her.

“It was cathartic, I’d said what I had to say, but I felt you only do one of these once in your life,” Brodsky remembers.

“Making a film about your family is not the big leagues, it’s a little like navel gazing, and I said, with a little bit of pride, that I wasn’t going to do that again.”

“What I never could have imagined,” she adds after a pause, “is that I would have a son who was deaf and that the saga would continue.”

FULL COVERAGE: 2019 Sundance Film Festival »

But Brodsky’s “Moonlight Sonata: Deafness in Three Movements” is, as its intricate title indicates, about much more than that.

Considered by the director to be “a spiritual sequel” to “Hear and Now,” “Moonlight Sonata” is an elegantly emotional film, incisive and reflective by turns, that deals feelingly not only with silence and hearing but youth and aging as well.

It does that by telling a trio of interconnected stories. There is Jonas, Irene’s deaf son who had cochlear implants when he was 4 and 8. There is Brodsky’s deaf father, who is growing older and dealing with the onset of dementia.

And then there is the wild-card presence of Ludwig van Beethoven and the marvelous piece of music he wrote just as he began to realize he was going deaf.

That a long-gestating story like this came to fruition owes something to the habit of Sheila Nevins, the visionary behind HBO Documentary Films and a mentor to Brodsky, to always ask how the family is doing.

When Nevins found out about Jonas’ childhood deafness, she suggested a development deal just to document the situation, an idea that did not initially lead to a film.

Even though the deal went away, the idea was out there, and when Nevins asked Brodsky about the family a few years ago, “I said, ‘Jonas is learning this thing Beethoven wrote when he was going deaf.’ Sheila said, ‘So when are we going to make this movie?’ ”

“And,” Brodsky replied, “call it ‘Moonlight Sonata.’ ”

Though it’s been more than a decade since “Hear and Now,” Brodsky says the challenges of this kind of filmmaking remain the same: “how to create a memoir without being maudlin or over-talking, and how to get the audience on board and guide them though the story.”

Jonas started learning piano, Brodsky says, to help him learn to navigate sound. When he was 11, he fell in love with “Moonlight Sonata,” a piece his paternal grandfather frequently played. His piano teacher felt it was a stretch for him, but the lessons that would become central to the film began.

Because the sonata was so linked to Beethoven’s deafness, Brodsky decided to make the story surrounding it part of the film. She used gorgeous animation (Jordan Domont was the illustrator, Brian Kinkley animation director) as the visual component.

Almost simultaneously with what was happening around the piano, Brodsky’s father, Paul Taylor, began to notice the onset of mental problems.

Taylor was especially close to Jonas, and the grandfather’s willingness to turn off his implants from time to time and live in silence, something he called “having a superpower,” came to play a part in the grandson’s life as well.

“It was a true stroke of luck that I had, the timing of both my son and my father, the intersection of where they both were,” Brodsky explains, still not believing it.

“My son was old enough to be articulate, to have a personality and to be open to me when I was filming. And he was able to appreciate his grandfather as someone special.

“My father knew something was happening, he knew he was losing his grasp, but he was still able to be an active participant. For those two to coincide, that is luck.”

Brodsky’s father had never refused to be filmed, but when he came to her house one evening to tell her he was having trouble getting access to his bank account, Brodsky says “it was a very difficult moment for me as a filmmaker.”

“I said, ‘May I put a mic on you?’ and my father said, ‘This is private, I would rather not talk about this on camera.’ But I talked him into it. To make a personal film, you’ve really got to want to tell the story; in a way, you have to be ruthless.”

The result is one of the film’s most moving scenes. There were similarly affecting intimate moments with Jonas, when he is crying post-cochlear surgery, that were difficult for Brodsky to film, but she felt she had to push forward.

“Someone said to me once that I wasn’t born with the ‘that’s good enough’ gene,” she explains. “If you don’t get the tough moments, if you’re not willing to bring out the camera when no one wants the camera on, you’re not going to have a story that’s honest.”

As Nevins wrote to Brodsky after seeing “Moonlight Sonata”: “Do you realize you hear what is unspoken? And maybe that is the birthright you have endured.”

Sundance 2019 Film Festival: See the latest video interviews

Video: Behind the scenes of the L.A. Times 2019 Sundance photo/video studio

Video: The 2019 Sundance Film Festival Boomerang Supercut

Video: How do you make the most of a small budget?

Video: Cast and filmmaker discuss trusting each other while shooting 'Premature'

3:12

Video: 'Brittany Runs a Marathon' breaks conventions and stereotypes

Video: Jillian Bell is tired of getting scripts about body image issues

Video: Jillian Bell lost 40 pounds for her role in 'Brittany Runs a Marathon'

Video: 'Brittany Runs a Marathon' actors break out of their sidekick roles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.