The #MeToo movement gets a movie about everyday harassment with Israel’s ‘Working Woman’

Hollywood has yet to make “#MeToo: The Movie,” and Israel already beat it to the punch. In fact, when writer-director Michal Aviad began researching her “Working Woman” back in 2012, “the only two major films on the subject [of sexual harassment] were ‘Disclosure’ and ‘Fatal Attraction.’ And both are about women harassing men.”

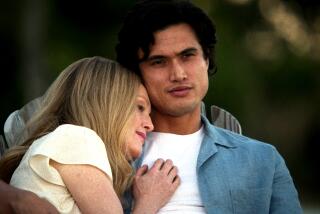

There are no boiling bunnies in Aviad’s new film, which stars Liron Ben-Shlush and Menashe Noy and opens Friday in Los Angeles. When the film played the Toronto International Film Festival last fall, one press account referred to the “living nightmare” suffered by its married heroine, Orna (Ben-Shlush), after her ostensibly benevolent boss Benny (Noy) makes it clear he has sexual designs on her.

But the extremes of a “nightmare” are precisely what Aviad avoids: Her portrayal of sexual harassment on the job is of something subtle, insidious and which can’t necessarily be expressed in words.

“When I make a film, there’s got to be something I need to learn,” said Aviad, who studied and made films in San Francisco during the ’80s and now teaches at Tel Aviv University. “For this one, I read women’s testimonies and went back to my experiences, and my friend’s experiences, but I couldn’t pinpoint what exactly it looks like ...

“What are the proximities of the bodies? What are the silences? What kind of tension is there? And while writing and thinking about it, I realized it’s as much physical as psychological.” Something that might best be addressed in film.

REVIEW: ‘Working Woman’ is a sexual harassment drama that cuts close to the bone »

“Working Woman” opens at a time when both Israel and the U.S. are reporting upticks in sexual harassment complaints; whether they can be credited to the #MeToo movement itself is, of course, a question. Equally unclear is whether the rightward, reactionary shift in each country has encouraged a rape-culture mentality in either.

Aviad, who agreed that Israel and the U.S. mirror each other in many ways, is not sure that there’s a direct correlation between current politics and current harassment. But she conceded that the climate doesn’t promote enlightened attitudes.

“In Israel, the regime is horrible,” she said. “Horrible. And the more the regime is right-wing, the more militaristic it becomes, the more men have license to do anything they want — because they are ‘heroes.’”

She said the laws both here and in Israel are good and have been since Anita Hill spoke out about Clarence Thomas. “But I think my film has really nothing to do with Israel either, but rather millions around the world who are in the same situation.”

Ben-Slush, who was four months pregnant (“and didn’t say anything about it”) when she auditioned for Aviad agreed. (Shooting was postponed.)

“I think that every woman, almost every woman, in Israel and in any other place in the world has a story of sexual harassment or being mistreated because of her gender,” she said. “Like every girl, l grew up thinking it’s part of being female. I know how it feels, sitting in a bus, as a teenager, with a stranger touching me, while blaming myself for wearing a short dress. I have experienced all sorts of those ‘small’ incidents. I adapted this basic feeling of fear and self-blame to the character.”

Orna certainly blames herself, and her guilt obscures her thinking. While her husband (Oshri Cohen) struggles to make a go of their new restaurant, Orna, with no experience, takes a job with her former commanding officer, Benny, at his real-estate development firm. (“The Israeli army is like college here,” Aviad said in New York. “It’s where you work together, bunk together, see each other all the time and keep loyalties 30 years later.”).

Orna is immediately and instinctively brilliant, pulling off one difficult deal after another. But when Benny tries to kiss her, it isn’t out of gratitude. And their dynamic irrevocably shifts.

Benny is not a monstrous character. He is in many ways sympathetic — which gives “Working Woman” much of its emotional complexity.

“The whole Harvey Weinstein scandal blew up during the first week of shooting,” said Noy (“Gett,” “Big Bad Wolves”). “But it wasn’t until a few weeks later, when the #MeToo movement started growing, that I realized the film was going to be released in a very sensitive period.”

Nevertheless, he said, “we agreed that the relationship between Benny and Orna will not be that of a predator versus prey.

“It was important to me that this complexity would come through in every aspect of him,” he said. “Benny is a successful Israeli man, an ex-military officer, a real-estate entrepreneur … he is a middle-aged man, and the presence of a young, attractive, talented woman is waking up hidden emotions inside him.

“Is he taking advantage of Orna? Is he just lusting after her? Is he falling for her? I wanted things to be unclear, vague; I wanted that both Orna and the audience not be able to tell whether Benny is falling in love or if he just gets carried away and loses control.”

At this stage of late capitalism, Aviad said, Israel is exactly like the United States, in that a huge percentage of its commerce involves selling. “Everyone is selling stuff and women are required to look attractive, which is another way of saying sexy,” she said. “And as soon as someone makes advances, it’s their fault for looking attractive.”

Orna feels complicit in her own victimization because she’s allowed herself to become indebted to Benny; to be afraid for her own career; to wear her hair long when Benny said she should let it down. It’s no less real than the kinds of things Harvey Weinstein is alleged to have done, but it’s far harder for the victims to explain their pain, or even the offenses that caused it.

“Two of the most beloved actors in Israel were accused of sexual harassment recently,” Aviad said. “We all know these guys personally; they’re not these movie villains. But you get an actor who flirts with an anonymous actress, she turns him down and then he tells the producer, ‘I can’t work with her.’ It’s this kind of stuff.

“The subtleties are far more interesting than Harvey Weinstein, because how many of these insane criminals exist? It’s more people who are doing things that used to be OK, but now are not OK.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.