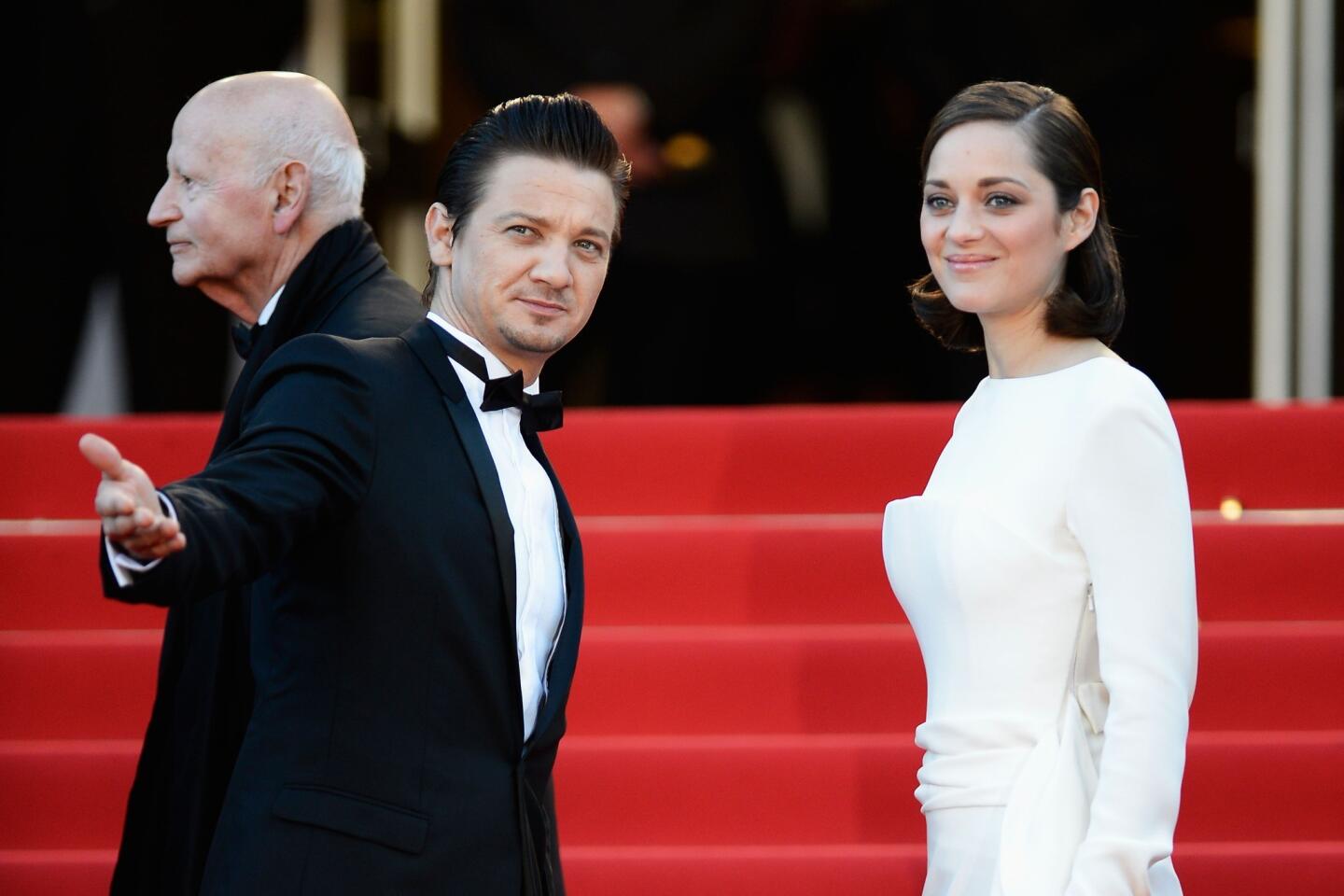

In ‘Touch of Sin,’ Jia Zhangke changes his style but not themes

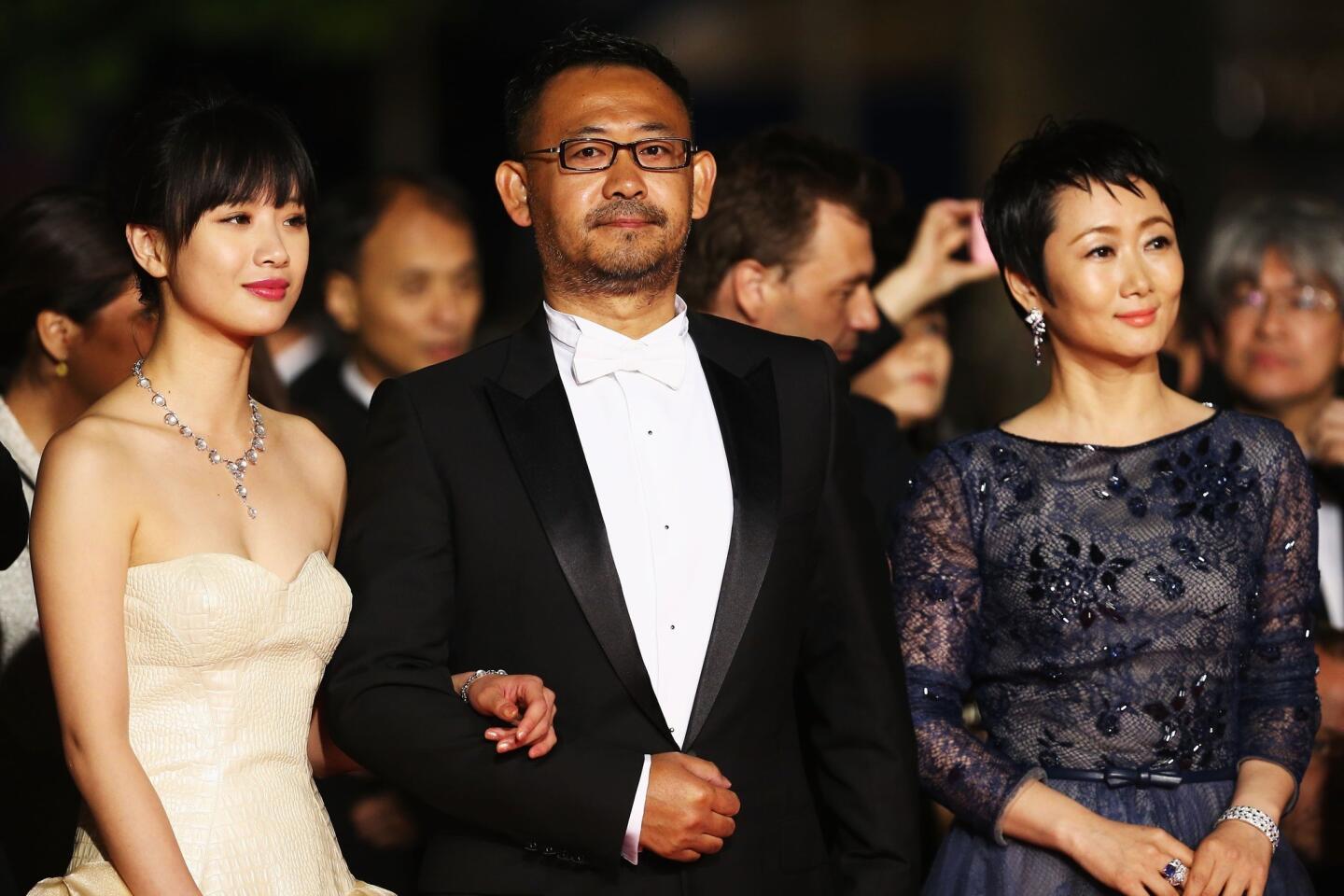

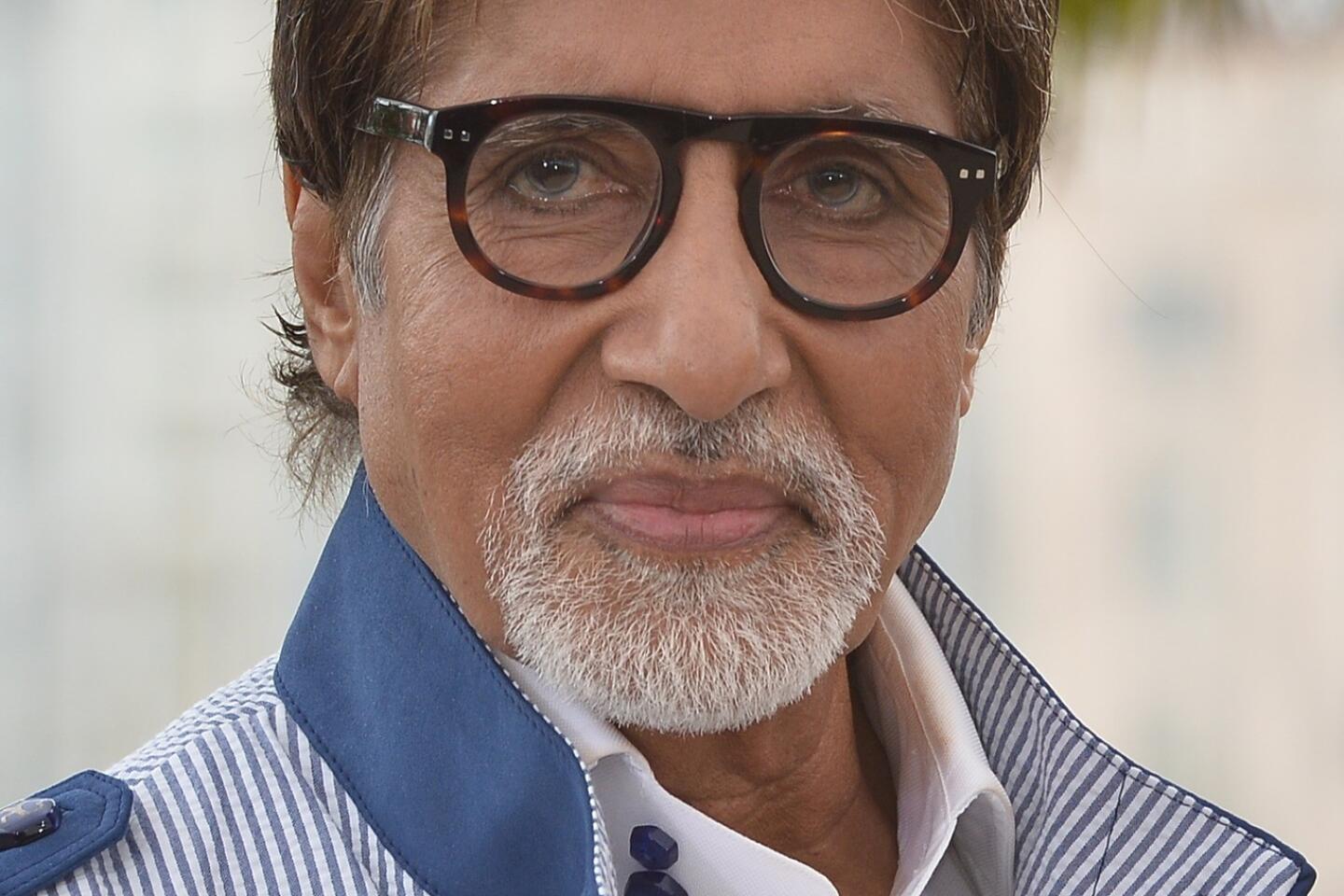

CANNES, France — “A Touch of Sin,” an early critical favorite among the films in the official competition at the Cannes Film Festival this year, has been widely greeted as signifying a new direction for the Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke. The claim is only partly true. A martial arts movie of sorts, this is the first genre picture by Jia, 43, known for such contemplative dramas and documentaries as “Still Life” (2006) and “24 City” (2008), which reveal how the forces of modernization and globalization have affected individual lives in 21st century China.

But in many ways “A Touch of Sin,” acquired this week for U.S. distribution by Kino Lorber, is not a departure at all. It simply finds a new form for themes that have underpinned Jia’s films since his debut “Xiao Wu” (1997), about a small-town pickpocket struggling to adapt to the new black-market economy. As always, this is a filmmaker who assumes the role of witness and conscience in a society characterized by convulsive change and a growing amnesia. In an ever more materialist society, where a booming economy has swept many to prosperity but left untold others behind, Jia is unmistakably on the side of the have-nots.

CHEAT SHEET: Cannes Film Festival 2013

A tragedy with elements of pulpy action and black comedy, “A Touch of Sin” tells four stories of social inequity, each one building to an act of violence. A miner tries to hold corrupt village leaders accountable; a migrant worker, returning home, gets his hands on a firearm; a sauna receptionist, involved with a married man, endures a series of humiliations; a young man drifts from thankless factory job to thankless service-industry job. The cumulative portrait, filled with despair and rage, is of modern-day China as a breeding ground for murderous rage and desperate amorality.

“I was motivated by anger,” Jia said at the beach at the Majestic Barriere hotel recently, speaking through an interpreter.

As in his other films — “Still Life,” which takes place in an ancient town being demolished to make way for the Three Gorges Dam, or “The World,” set in an Epcot-like theme park in Beijing — fiction is strongly rooted in documentary. Jia began with actual news stories of people pushed to the edge and resorting to fatal measures. (One segment refers to the suicides at the electronics manufacturer Foxconn, which have continued in recent weeks.)

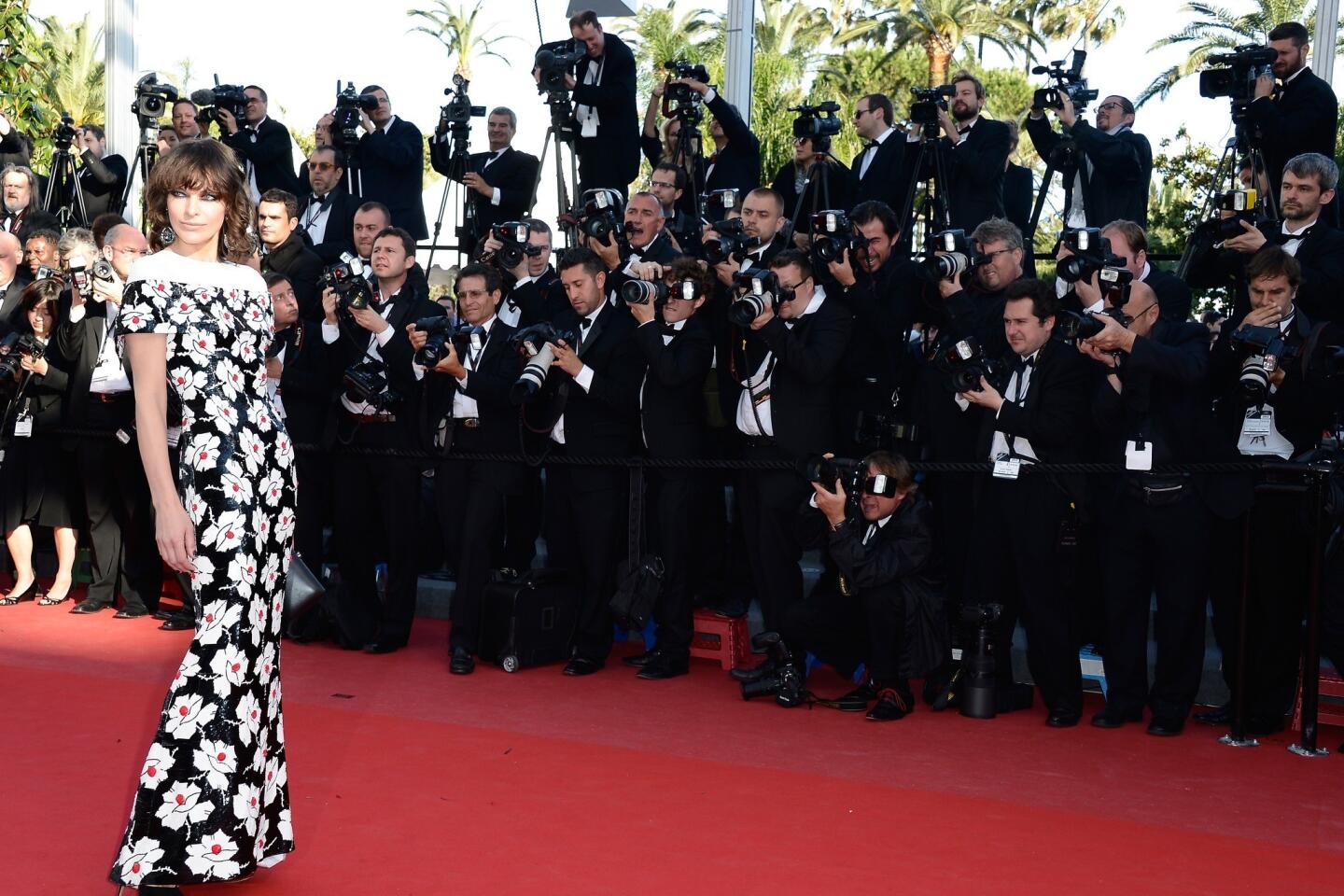

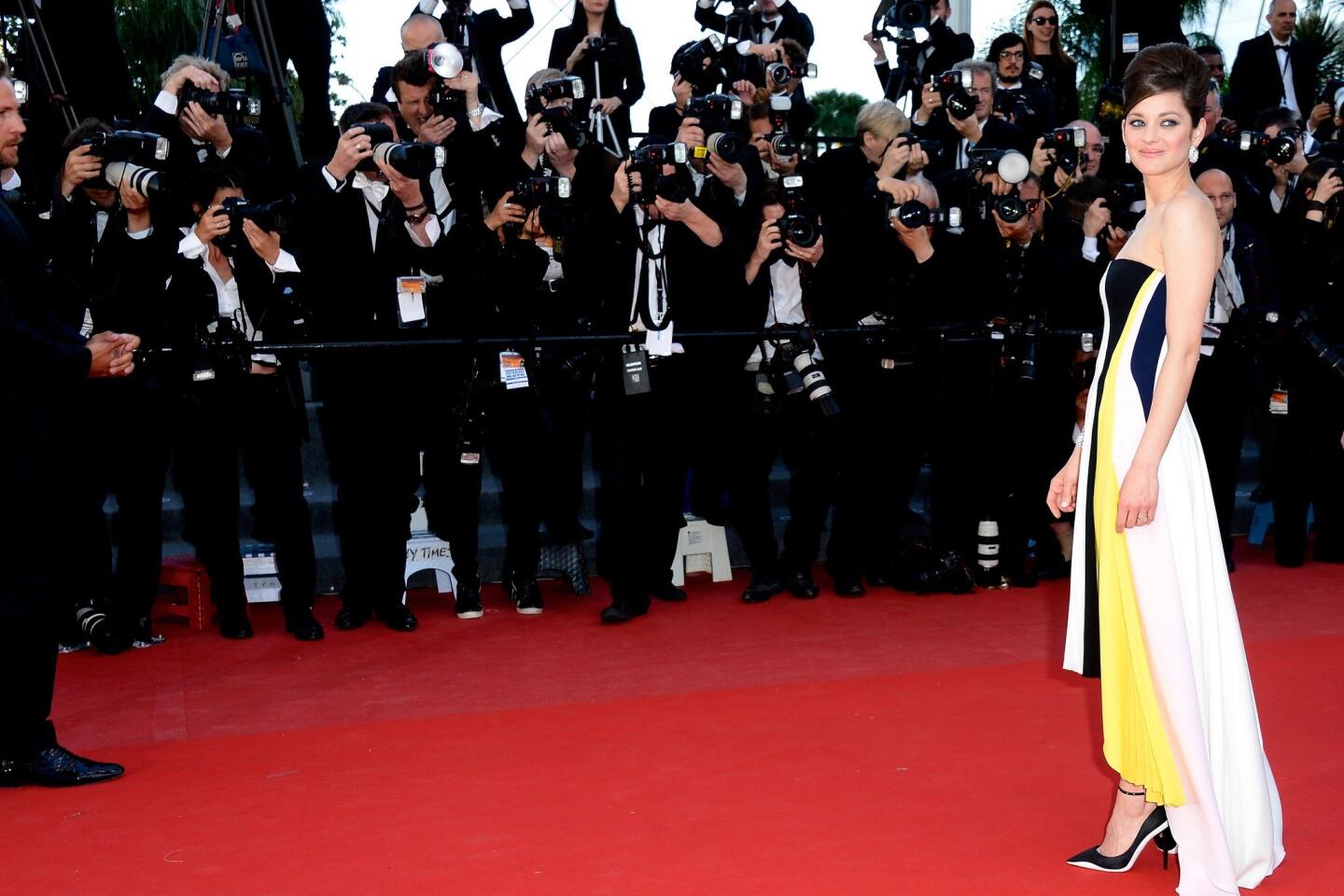

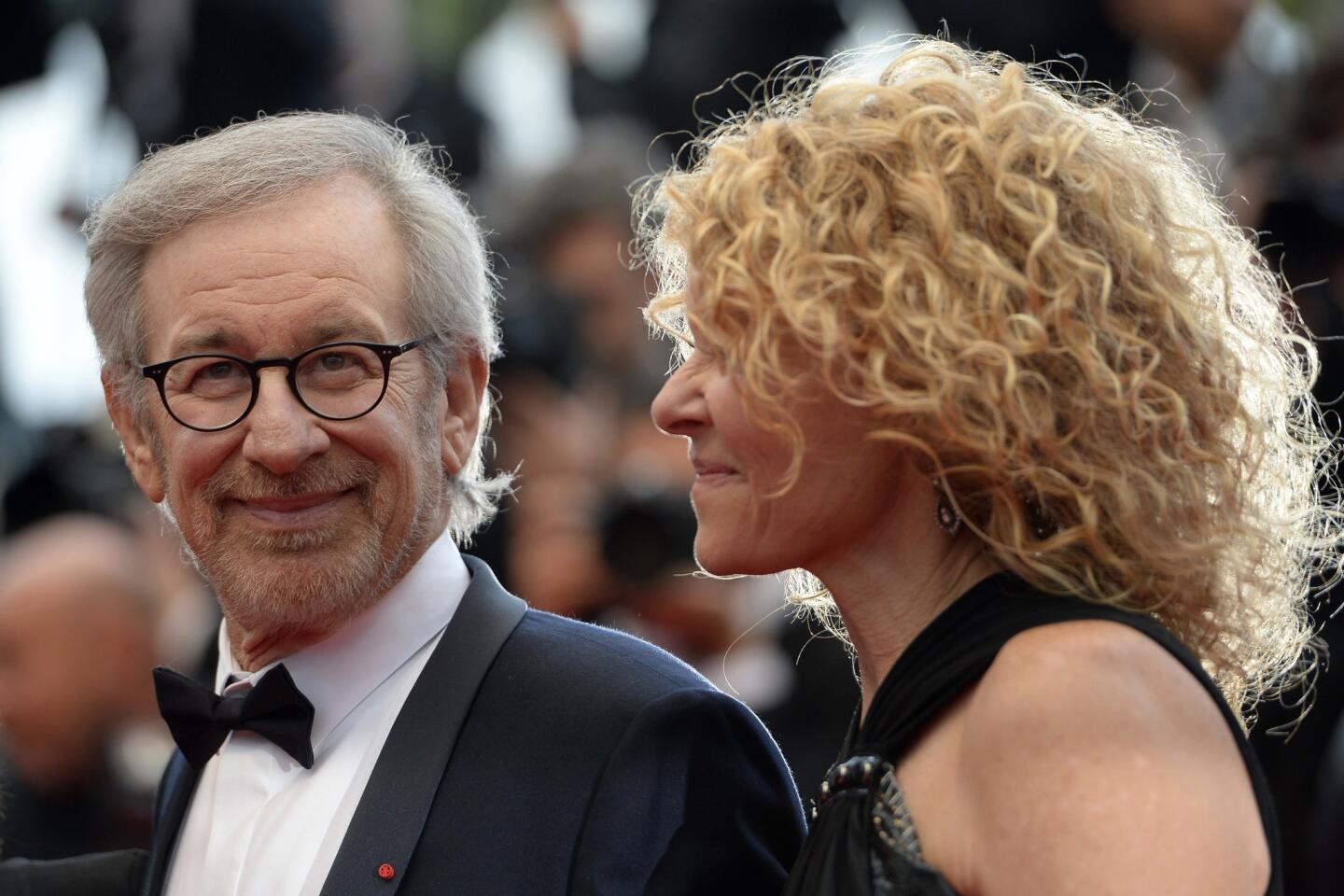

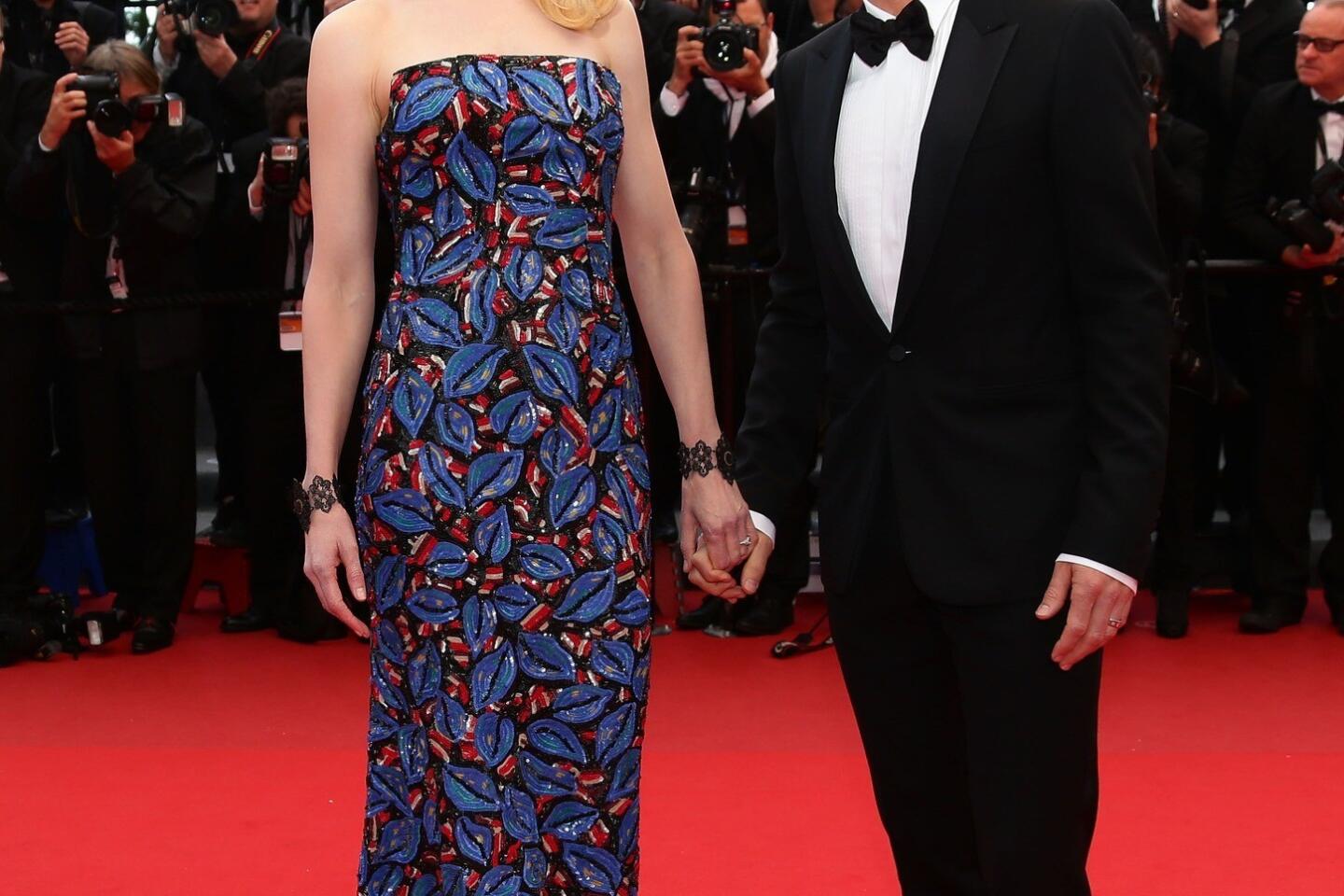

PHOTOS: Cannes Film Festival 2013

“These are people who feel they have no other option but violence,” Jia said. Though such events are not necessarily new, he added, they have been widely circulated and discussed in recent years on social-media platforms such as Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter.

“There’s suddenly a big dose of violence in everyday life,” he said. “But the problem is that new events keep coming, so old ones keep being forgotten.”

Jia came of age in the 1980s, as China was yielding to an influx of previously banned music, art and books, and his movies have always been attentive to how young people absorb and find meaning in pop culture. His 2000 epic “Platform” traces the “open door policy” of the 1980s by following the members of a performance troupe from the provinces as they graduate from Maoist propaganda skits to break-dancing demonstrations.

But “A Touch of Sin” is his first film modeled on a popular genre. Jia started out, as he often does, with field work, interviewing people with knowledge of the events and visiting the regions where they took place (which included his home province of Shanxi, frequently depicted in his films), and the industrial city of Dongguan, known among other things for its thriving sex trade.

As he was writing the script, he realized that the stories he was telling were compatible with the wuxia, or martial arts, genre. (“A Touch of Sin” alludes to the director King Hu’s 1971 wuxia classic “A Touch of Zen.”) “For me, martial-arts movies are deeply related to politics,” Jia said, adding that this was especially so with King Hu’s films, which were often about “how individuals reacted to political oppression in the Ming Dynasty.”

Jia started his career as a so-called underground filmmaker, making movies independently and without state approval, but since “The World” he has been able to work within the system while retaining his voice as an outspoken social critic. The Chinese filmmaker Lou Ye received a five-year ban from filmmaking for screening “Summer Palace,” which partly concerns the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, at Cannes in 2006 without government approval. But the state-backed Shanghai Film Group is a co-producer of “A Touch of Sin” and the version of the film that screened in Cannes has been approved for theatrical release in China this year — to his surprise, Jia said.

If many recent Chinese films have shied away from overt social commentary, it may be less for political than economic reasons. “Chinese films have become so massively commercialized,” Jia said. “You risk having to pass censorship and you also risk the film not selling well.” He added that the most daring and political works of recent Chinese cinema could be found in the realm of documentary, which has boomed with the availability of digital technology, resulting in such major works as Wang Bing’s “West of the Tracks” and Zhao Liang’s “Petition.”

“A Touch of Sin” has already sparked debate in the Chinese press, with much discussion about its scenes of extreme violence. “Violence has long been neglected in Chinese culture,” Jia said. “We don’t talk about it, we don’t understand it. In a way movies can do a lot in terms of inspiring people to confront, to understand, to feel violence. If you don’t allow violence to be discussed in movies, we’re just going to become a more violent country.”

Toward the end of the film, a woman in a traditional Chinese opera performance sings the line “Do you understand your sin?” Asked if there is a principal sin that the title refers to, Jia said: “It’s about how we tolerate injustice, the gap between the rich and the poor. More than anything I think silence is a sin.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.