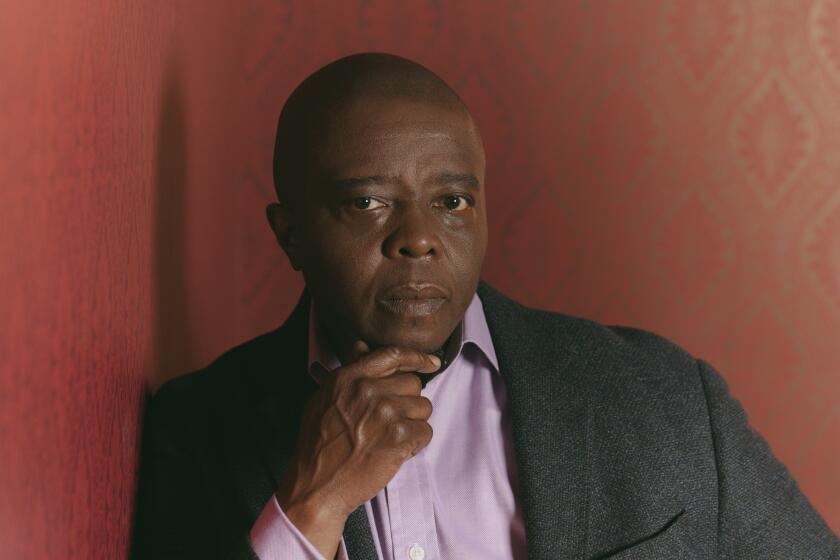

Robert Redford faces elemental challenge in ‘All Is Lost’

Robert Redford was going down with the ship.

Yes, the character he plays in writer-director J.C. Chandor’s “All Is Lost,” which arrives in theaters Friday, is a lone traveler on the Indian Ocean whose sailboat is taking on water from a gash in its hull. But this water emergency wasn’t in Chandor’s screenplay.

Filming in the same massive outdoor tank that James Cameron used to make “Titanic” in Baja California, Chandor was shooting Redford inside the cramped quarters of the 39-foot Virginia Jean. The sailboat was half-submerged, with the actor and a skeletal crew sloshing through waist-deep water aboard the vessel, the script supervisor hiding in the boat’s tiny head.

PHOTOS: Robert Redford - Career in pictures

Suddenly, an assistant director yelled: “Out of the boat! Out of the boat! Everybody, out of the boat!” The crew, toting its $500,000 digital camera, quickly climbed out. “But the assistant director doesn’t say the boat is sinking,” Redford recalled. “And then I thought, well, maybe I should get out, too.”

The actor and his director scrambled out just a few seconds before the Virginia Jean scuttled in some 60 feet of water.

“Just to be clear, I was the last one off,” Chandor, 39, said. “I really didn’t want to be the guy who killed Robert Redford.”

If making the rest of the movie wasn’t always as dangerous, it certainly was arduous.

The physical production and its inherent corporal tests were just half the battle. Redford, 77, did more of his own stunts than he originally had intended. He said he permanently lost 60% of the hearing in one ear after high-pressure water was sprayed onto him to simulate a storm.

But far more challenging for Chandor was how to tell his story using only one actor and almost zero dialogue, without resorting to any of the tropes of the castaway genre.

FULL COVERAGE: Sundance Film Festival 2013

From the story’s inception, Chandor decided he would resist using voice-over, flashbacks or a random piece of sporting-equipment-as-sounding-board to illuminate his character’s back story, thoughts or emotions. Instead, action would be everything. It would be a total turnabout from his previous film, 2011’s “Margin Call,” a dialogue-heavy Wall Street thriller with an ensemble cast.

Just as Redford’s sailor has to patch the fissure in his listing boat, the audience would have to fill in all of the story’s expositional holes.

Redford initially feared that chasm would leave him as an actor as adrift as his solitary seaman. The “All the President’s Men” and “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” veteran would pepper Chandor with questions about his character, who doesn’t even have a name. Who is he? Where is he from? Does he have a family? Why is he on this trip? But Chandor wasn’t sharing.

“He never really answered. He talked all around it. So you have to do a lot of deciphering,” Redford said. “And I realized that, well, if that’s where he’s going that’s fine with me. So I stopped asking.”

“All Is Lost” starts with a letter, just as Chandor’s writing of the movie did.

“I’m sorry. I know that means little at this point, but I am. I tried. I think you would all agree that I tried. To be true, to be strong, to be kind, to love, to be right. But I wasn’t.”

FULL COVERAGE: Fall Movie Sneaks 2013

Exactly what Our Man (as Redford’s character is called in Chandor’s screenplay) is apologizing for is unclear. But two thoughts come to mind. First, whatever has happened in his life probably served as a catalyst for his solo voyage. Second, even when faced with desperate circumstances that demand unvarnished candor, the sailor still can’t quite say what he really feels.

“Even in his last note,” Chandor said, “he was unable to communicate — he was blocked.”

Chandor worked on that letter for weeks in 2010, revising the missive on train rides from Providence, R.I., into New York, where he was finishing “Margin Call.” He wanted the language set before penning the rest of his short, 31-page script.

“I love survival movies, but I thought that you had to play the same narrative tricks,” Chandor said, referring to techniques like voice-over and inanimate objects (“Cast Away”), flashbacks (“Touching the Void”) or a video camera (“127 Hours”). “So it really became, can you really make a movie like this — which is just to show what you are doing to stay alive? If the guy isn’t going to talk, how do you make it a swashbuckling adventure?”

That adventure begins as soon as the film does. Soon after Redford is heard reading his letter, the film cuts back to eight days earlier, when we hear the gentle lapping of water (the sound design, by Steve Boeddeker and Richard Hymns, is extraordinarily precise). For Our Man, the sound is ominous, signaling that there has been a breach in his sailboat.

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

In the middle of nowhere in the Indian Ocean, the Virginia Jean has collided with a massive steel cargo container — the kind you’d see on the back of a semi trailer or atop a train car — that apparently has washed off a freighter. The resulting cut at the boat’s waterline has partially flooded the sailing vessel; critically, the seawater has fried the radio and navigation equipment.

Our Man quickly needs to begin repairs to make his craft seaworthy. He’s close to shipping lanes, but without a radio, GPS or radar, he can’t communicate and see what the forecast holds, including a storm thundering over the horizon. He tries to teach himself celestial navigation.

“He doesn’t have a lot of time to reflect,” Redford said. “It’s completely in and of the moment.”

As much as “All Is Lost” is focused on the mechanics of staying alive at sea — how can you get food and water when your stores are fouled and nearly gone?— the film ultimately becomes an existential story of a man combating not just nature but himself.

Surprisingly, Chandor didn’t have a particular actor in mind when he was writing the film — and certainly not Redford. But that all changed at the Sundance Film Festival.

When Chandor took “Margin Call” to the Utah gathering in January 2011, he was invited to a filmmakers’ brunch hosted by Redford, founder of the festival. Chandor was seated far back in a room where Redford was speaking, but the public address system wasn’t functioning properly. Chandor could see that Redford was talking, but couldn’t hear a thing he said. A technician then connected a speaker right next to Chandor, and the actor’s distinctive voice came booming into the director’s ears.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

Chandor was immediately struck by an idea: What if you stripped a performer as well-known as Redford of something as integral to his acting as his voice? Too shy to ask Redford at Sundance about potential interest, Chandor waited until his brief script was completed. Just minutes into his first meeting with Chandor, Redford agreed to star in the film — startling the filmmaker with the speed of his decision.

Redford knew it would be a challenge: Unable to banter with other performers or slide by on his charisma and looks, the actor was forced to do things — acting on an almost elemental level — that he hadn’t previously done. While Redford’s character doesn’t verbalize feelings like despair and hopelessness, he’s clearly facing his own imminent mortality and knows that he may not have what it takes to get the job done.

“I think it had to do with trusting him,” Redford said of accepting a part that relied on just doing, not saying. “Because before, whenever I would challenge myself about saying yes, it had to do with how much faith I had in that person — the director, the scriptwriter — to deliver the goods. And I had faith in J.C.”

Chandor believes the journey of the character and the actor in the film’s third act are eerily parallel. “He’s forcing himself as an actor to do things he wasn’t sure he could do,” the director said. “He has admitted the physical sense — that he’s going to push himself. Now, as an actor, he has to force himself to go deeper.”

Initially, Redford and Chandor planned for a double to perform many of the film’s more dangerous stunts, including being washed overboard and the Victoria Jean’s capsizing. But once filming started, Redford volunteered to act in several action sequences that he and Chandor had assumed he would watch from the sidelines.

PHOTOS: Robert Redford - Career in pictures

“It was my ego,” Redford said. “My ego jumped in and said, ‘Hey, you can do this. You can do this. Let’s see if you can do this. Let’s see if you can jump off the boat and dive into the… Do it!’

“I was wet all the time. They hit me with water when I was dry; to do another take I’d have to go get into dry clothes again. It was not fun.”

Redford said he asked for (and Chandor granted him) several scenes where his character was doing nothing but thinking — not repairing or swimming or struggling. Redford, who grew up in Santa Monica, said during those moments he thought of his youth sitting on the beach, imagining the enormity and beauty of the ocean, and how insignificant man is in comparison.

“I don’t know how this will play out in the public domain. I have no ideas,” Redford said of his worries about how “All Is Lost” will be received by general moviegoers after playing at festivals in Cannes, Telluride and Toronto this year.

“To be appreciated in a festival is one thing. When you go into common ground, it could be another,” he said. “I mean, who knows? I just liked doing it.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.