A Second Look: ‘L’enfance nue,’ Out of the shadows of the French New Wave

More than anything else, it was probably Maurice Pialat’s late start that accounts for his unfairly diminished reputation in the United States. Recognized in France as one of the major filmmakers of the second half of the 20th century, Pialat (1925-2003) belonged to the same generation as Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and the other leading figures of the French New Wave.

He made his first feature a decade after his contemporaries — by which time he was in his mid-40s, a failed painter — and for international audiences, he has always remained in the shadows of the titans of French cinema. Even though he earned widespread acclaim for 1991’s “Van Gogh,” won the Palme d’Or at Cannes for “Under the Sun of Satan” (1987) and exerts an influence on today’s leading French directors that cannot be understated, most of Pialat’s features remain little known and hard to see in the U.S.

Pialat’s first feature film, “L’enfance nue” (Naked Childhood, 1968), out on DVD this week from the Criterion Collection, can be seen as a companion piece — or perhaps a response — to François Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” (1959), the beloved landmark that was synonymous with the New Wave’s first flowering. Truffaut was a producer on “L’enfance nue” and an early champion of Pialat’s, but their films, although both focused on the travails of troubled boys, diverge in tone and approach. One critical difference, as the writer and filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin put it: “We are looking at Truffaut’s imp. But we are seeing through the eyes of Pialat’s.”

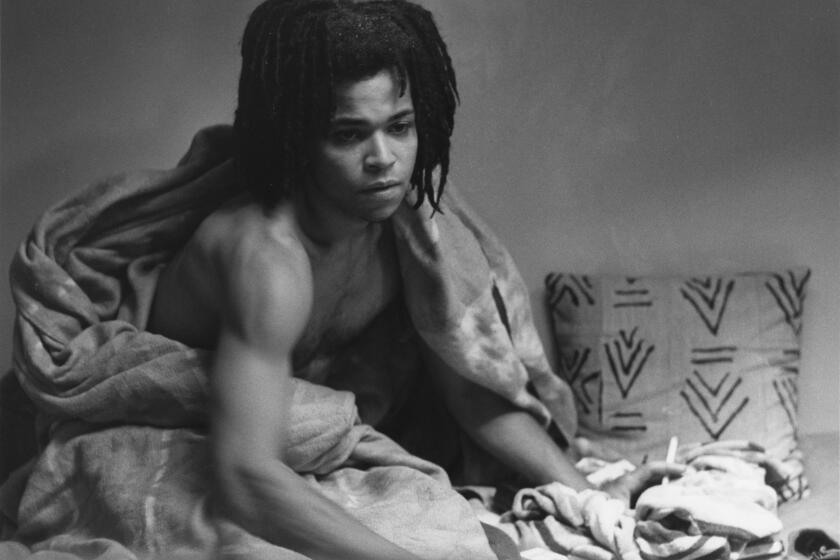

One of the most moving films about childhood ever made, “L’enfance nue” is also one of the most tough-minded. Pialat’s 10-year-old protagonist, François (played by Michel Terrazon), is not exactly the plucky rebel-urchin we often find in coming-of-age movies. Abandoned by his mother, shunted from one foster home to another, he is withdrawn and prone to bouts of violence, already something of an advanced delinquent. Within the first few minutes of the film, we see him engaged in acts of theft, vandalism and animal cruelty (he drops a cat down a stairwell).

But despite a mean streak and sociopathic tendencies, François is also not a demonized bad seed. He’s capable of tenderness and remorse — he cares for the cat that he nearly killed, and, while saying goodbye to the frazzled foster mother who is sending him back to the social workers, presents her a gift.

“L’enfance nue” chronicles one representative cycle in François’ unstable life: leaving one home, being shipped to an orphanage and moving into another home, where he both adapts and fails to do so and where the prospect of his departure, under some circumstance or other, seems inevitable. At both homes, even though his custodians are kindly and well meaning, there is a clear assumption that the boy is a temporary placement (we see this in his makeshift bedroom and hear it in the way he’s introduced to others).

Far from a didactic social-issue film, “L’enfance nue” declines to point fingers. The film doesn’t blame negligent authorities or foster parents. There are neither saints nor villains, people act out of both self-interest and generosity, and it is through this casual insistence on complexity that Pialat is able to create, often in just a handful of scenes, some remarkably vivid supporting characters.

Most memorable are François’ second set of foster parents, the Thierrys, an elderly couple (nonprofessional actors more or less playing themselves) who already have taken in a teenage boy and are also caring for the wife’s ailing mother. In one indelibly intimate scene, the Thierrys sit across a kitchen table from the boys, the wife on her husband’s lap, gently swaying as they tell their young charges about their lives and why they decided to take them in.

Completed in 1968, the year of the barricades, which spurred many French filmmakers to contemplate the buildup to the riots in Paris (and the deflating aftermath), “L’enfance nue” sidesteps ideology (even though the opening shot is of a demonstration) and expands instead into a richly observed panorama of French working-class life.

With its clipped rhythms and documentary-like directness, it’s a work of startling immediacy, concerned above all with how François reacts to the world around him, to his ever-changing circumstances. It establishes the searching sensibility that would characterize Pialat’s cinema, bruisingly alive and fully in the moment.

calendar@latimes.com

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.