Directors Roundtable: 5 discuss inevitable bad days

Everybody has them — waiters, bus drivers, lawyers: a bad day.

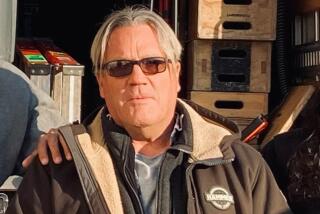

For a filmmaker with a hundred-strong crew in the wings and millions of dollars on the line, the stakes can be considerably higher when things go off the rails. In this edited excerpt from the third annual Envelope Directors’ Roundtable, the filmmakers behind some of this season’s most talked about movies — Martin Scorsese (“Hugo”), Michel Hazanavicius (“The Artist”), Alexander Payne (“The Descendants”), George Clooney (“The Ides of March”) and Stephen Daldry (“Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close”) — discuss surviving bad days, the challenges of directing scripts they’ve written, earning movie set trust and the value of reviews and test screenings.

How do you define a bad day on set?

Martin Scorsese: You don’t have the spark [or] something is lost and you don’t get the work. Like “The Last Temptation of Christ,” where we were in Morocco. You’re in the desert shooting, and it’s supposed to be the River Jordan and, long story, basically there’s no water in the desert and we had to make up a river. We had to baptize Jesus in the river. So we got there and the river disappeared. We literally shot only three setups for the one day. That meant that we had to do the entire sequence the next day — in one day. And that’s when you realize you’ve got nothing, and also we don’t have any money. We can’t continue, but we’ve got to continue, so that means we start cutting setups, move this over there. Get someone to just pour water in.

Michel Hazanavicius: The thing I hate is when the small-part actors, the one who has to be here for one day, you miscast it, then you’re dead. Because you know it’s not his fault, it’s not yours, but you know that the character you dreamed that could be good won’t be good.

George Clooney: One line, and you know it’ll take everyone in the audience out of the movie for 10 minutes.

Alexander Payne: We call them day players. I had one on “About Schmidt.” It was the hardest part to cast in the whole damn film. Probably read 80 guys for this part. “OK, let’s pick this guy. I’ll try to make him work.” He was terrible. Take after take after take. That’s No. 1. No. 2 is when the actor doesn’t know his or her dialogue.

GC: You also had an interesting issue when we had to go out on the water in the little canoe [at the end of “The Descendants”]. You can’t just go out with a camera and shoot. You’re with 100 people on two different barges right behind you.

AP: For a nice little scene of a couple people spreading ashes, it’s like we called out the damn National Guard.

MH: My worst day of shooting was for an advertisement. It was supposed to be young kids, like 10 or 12, drinking orange juice on a boat and being happy. And they were vomiting, they were gray-green.

George, Alexander and Michel, how is your job as a director changed by the fact that you have written the movie you’re directing?

GC: In some ways it’s obviously easier because you’re on the set. Because the truth of the matter is things that you wrote in a dark room are going to change. It’s helpful to be able to just do that on the set and not worry about it.

AP: I’ve never storyboarded in my life but the fact that I’ve written it becomes a sort of mental storyboard. That’s the first visualization of the film.

MH: I think it makes things easier also because people maybe trust you more, and they say, “OK, this is his story, let him do what he wants to do.”

How critical is trust to the process?

MS: It’s all about trust.

George, how did you get trust on the first film you directed?

GC: That’s hard, because I’m trying to convince people that I’m directing now and not acting. Forward momentum is a really important part of it. Because if actors smell blood in the water, the first thing they do is sort of take over, if they think they can.

What does that mean?

GC: I started out doing television — “ER,” where kids are dying every week and I’m a pediatrician. Every director that comes on, and it’s a different one every week, says, “OK, well this kid dies, it gets you right here.” And you’re like, “Yeah, yeah, I got it.” “No, but I mean, really, it kinda gets you.” And you go, “Yeah, but it got me last week with the other director.” I can’t be weeping in 22 episodes. So you find yourself as an actor becoming completely immune to direction. And then, when I first started doing features, I worked with Robert Rodriguez, and he says, “OK, so you do this, you do this.” And I’m like, “Got it.” And then I just did what I thought I would do. And after about three days of that he came over and he goes, “You’re not doing anything I said.” And I was like, “You’re absolutely right. I wasn’t. I apologize.” I’d stopped listening.

Stephen Daldry: The director’s worst fear is when an actor says “my character.” Well, hang on, he’s not your character. First of all, it’s our character, we wrote it out. If you’re getting into that place where you’re defending yourself like that, it’s all lost.

AP: I think the best actors study the directors to know in an unspoken way what movie am I in. What is this director’s aesthetic? How can I be in the same movie?

Do you guys pay attention to reviews?

MS: At this point you can’t ... it got to a point where it’s very difficult for me to look at them and ...

So you don’t even read them.

MS: Well, if you read the good ones you might believe those. Then if you read the bad ones, you certainly believe those.

GC: You always believe the bad ones more.

MH: I force myself not to believe the good ones and the bad ones, but I can read it. And sometimes actually you learn something, not because of what they say, but because they force you to talk so much [about your film]. And you talk and you talk and you discover some things that you did instinctively, and you find the current of what you’re doing.

Are test screenings a necessarily evil, are they helpful for you as a filmmaker?

SD: I love test screenings.

Why?

SD: You find out what people see. I don’t use test screenings to change the film necessarily to what they want, but to know whether they’re following the story that you want to tell or not.

MS: It’s very different previewing a film like “Kundun,” that I made, and previewing “Goodfellas,” which was disastrous. Or previewing “Hugo,” for example. Each one is different, and what scares me the most is the confidence of the backers of the studio.

That they will listen to those scores and...

MS: Everything. In other words you get beaten up. You go in and you get beaten up but you know out of that comes a shaping of the picture. There’s also things you shouldn’t listen to, but you’ve got to decide that. But it’s losing the confidence in the picture that worries me in terms of promoting the film.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.