‘Magic/Bird’ brings the rivalry — and friendship —to Broadway

NEW YORK—The American theater regularly portrays outsized figures we know from history. ESPN routinely packages narratives of athletes we know from sports broadcasts.

Rarely, however, does one production seek to do both.

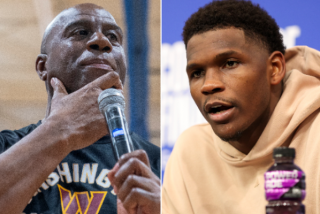

Like its subjects, “Magic/Bird,” a new Broadway show about the basketball icons, is the most unlikely of pairings. It combines traditional stage drama with slick sports multimedia — all in the service of an intimate story about that most complex of sports rivalries and friendships, the one between Magic Johnson and Larry Bird.

“On one level this is a story of two guys who hate each other and then grow to like each other. But it’s also two people who are so different that in some ways they’re really two sides of the same person, two sides of all of us,” said Eric Simonson, who wrote the play, which opened Wednesday night.

A celebrity-packed crowd, including both its subjects, was expected to attend. (This is no small feat: the down-home Bird has not only never attended a play on Broadway — he’s never been to a play, period.)

Simonson was sitting in the balcony of the Longacre Theater, overlooking a stage tricked out in basketball hoops and parquet tiles. The aesthetic of the old Boston Garden is one of many realistic touches he and director Thomas Kail incorporated for their production about the legendary Laker and Celtic. (Those tight 1980s shorts, incidentally, are another). Simonson and Kail drew from game footage, newspaper clips, an HBO documentary, their own interviews and even TV commercial outtakes to craft their dramatization.

The basics of “Magic/Bird” should be familiar to a fair number of sports fans — telling a story that long predates Johnson’s latest incarnation as savior of the Dodgers. Essentially beginning at the pair’s showdown in the 1979 NCAA final, it follows them to the NBA, where they are each expected to revive a struggling team and league, and moves on to a prime-time rivalry and numerous championships, including five titles for the Lakers.

Along the way, the play teases out their differences. Bird (played by Tug Coker, who nails the athlete’s sleepy drawl) is the shy kid from French Lick, Ind., who would rather be building retaining walls on his rural property when he’s not playing basketball. Earvin Johnson (Kevin Daniels), the extrovert with the million-dollar smile, has a penchant for the pleasures of the Playboy Mansion.

Yet each fed off the other’s greatness. Magic’s championship in his first season in the NBA gets Bird burned up, while Magic stews over Bird’s rookie of the year award. As their careers unfold, they each would check box scores to see how the other did on a given night, locked in a kind of rope-pulley dynamic in which the movement of one exerts force on the other.

They also had a prickly relationship over the years. But “Magic/Bird” shows how that rivalry gave way to grudging respect and, eventually, to a deep fondness.

“You’d never think they would have anything in common, and yet the fact that they were each so special made them understand each other in a way no one else could,” Daniels said.

Although “Magic/Bird” doesn’t poke too much at the stars — producers have the blessing and marketing cooperation of the NBA — it doesn’t entirely shy away from their foibles either, such as Bird’s fear of the spotlight, and Johnson’s intense need for it.

“Everybody else likes me,” Johnson says to Bird in the show. “Why not you?”

Said Coker, “These guys are superheroes who had insecurities. That’s what we’re trying to show. It’s not a story about two great people but about what two people had to overcome to be great.”

Race is a key issue here too; Simonson explores the subject in sometimes heated bar stool conversations between fans of the predominantly black Lakers team and the heavily white Celtics.

For much of the show, theatergoers watch the players separately, as they step forward from different parts of the stage or alternate taking center stage. Mostly, the two leads interact with other people in their lives (for instance, Jerry Buss, Pat Riley and Red Auerbach — all played by Peter Scolari, in a remarkably shape-shifting turn).

But the play builds to a conversation that took place at a real-life lunch between Magic and Bird at Bird’s French Lick home as the stars are shooting a sneaker commercial. (The details are largely unknown; Simonson constructed what they might have talked about, primarily their backgrounds and attitudes about fame and work ethics.) The bond between them is forged that day, and rivalry morphs into friendship.

Though a number of drills and one-on-one moves are in display, “Magic/Bird” contains no full-court basketball scenes. Instead, Kail pauses the dialogue at key moments to play video clips, as a giant screen at the back of the stage comes alive to show moments such as Magic’s running “junior, junior skyhook” to give the Lakers a crucial victory over the Celtics in Game 4 of the 1987 NBA Finals.

“We usually experience sports sitting at home with a few people watching it on television, or with 20,000 people in an arena,” Kail said. “What we wanted to give you was something in-between.”

Even in previews, the play became a fan-fueled sports contest.

The 1980s New York Knicks star Bernard King turned up one night to see what the fuss was about. At another performance, a group of Indiana Pacers, in town to play the Nets, came in and loomed over the other theatergoers. Kail worried about how they might report back to Bird, now in the Pacers’ front office.

Theater patrons have also been showing up wearing Chris Paul and other NBA stars’ jerseys, as well as vintage Lakers and Celtics gear. Even backstage feels a little like a locker room, with basketball uniforms hanging among the usual Broadway props.

The show was born when the Broadway producers Tony Ponturo and Fran Kirmser, who also produced “Lombardi,” approached the NBA and the two stars with an idea of turning the stuff of sports lore into a Broadway production. The pair are developing a mini-franchise in sports-themed theater, which Kirmser said “can offer much needed inspiration in what are very difficult times.” The duo, who are developing another sports-themed show, say pro athletics also plays well to young males, who are not Broadway’s bread and butter.)

Simonson and Kail also previously worked on “Lombardi,” about the legendary Green Bay Packers coach. (Each has been nominated for Tony Awards, Kail most famously for “In the Heights.) They said they were moved to work on the show in part because its two subjects are so hard to truly know. (Neither are fans of the Lakers or Celtics; Simonson, 51, grew up in the Midwest and followed the Chicago Bulls, while Kail, 35, was a suburban D.C. kid who rooted for Washington’s NBA team.)

After the stars agreed to participate, Johnson sat in on a reading in Los Angeles, offering suggestions and encouragement to the actors; he also sat for interviews with Daniels, Simonson and Kail. The Lakers legend has been supportive of the show — he talked about it on the CBS morning show Tuesday, was scheduled to appear with Bird on David Letterman’s show Wednesday and met with other selected media. His absence from the Dodgers home opener Tuesday raised eyebrows, given his involvement in the team’s new ownership.

Bird was less forthcoming with the show’s creators, though he did meet with Simonson and make himself available by phone to others.

Kail acknowledged that the show was a struggle to cast.

He and Simonson settled on the two actors, who were both relative unknowns, because they were both well above 6 feet and had some basketball skills, and also because Coker had Bird’s intensity and Daniels radiated Johnson’s magnetism.

Toward the end of the show, Bird is shown doing what he did thousands of times in his career: passing to an open teammate. It is November 1991, and the forward has just learned that his Lakers rival has been diagnosed with the HIV virus. Stunned, Bird eventually makes his way to his next game, barely able to play. As the on-stage action unfolds, the screen shows a clip of Bird tossing a Magic-esque no-look pass — paying homage, in his own low-key way, to his ill friend.

After the two play together on the 1992 Olympic Dream Team, the show’s closing scene suggests both Johnson and Bird moving on to the next phase of their lives. Like other aspects of the play, the moment highlights what the men were like when they weren’t displaying their mastery on the court.

“In our society, we make mortals into gods,” Simonson said. “This is about what happens when those gods go back to being mortals.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.