Alvin Ailey’s legacy has been kept, and expanded

Judith Jamison can recall vividly the April 1989 lunch in St. Louis when Alvin Ailey designated her his artistic heir. “He said, ‘I’m not doing well; you know I’m sick, and I’d like you to take over the company.’ I said, ‘Sure, of course, Alvin.’

“That was it. The decision to do it was instantaneous.”

Jamison, 66, was speaking last month in her comfortable office on an upper floor of the company’s sleek, spacious Midtown headquarters. The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater recently had completed its annual five-week New York City season, during which Jamison’s 20th anniversary as artistic director was honored and celebrated in various forms.

The celebration continues during the company’s 20-city national tour, which brings it to the Orange County Performing Arts Center for seven performances this week. Two of the programs include “Best of 20 Years,” an extensive parade of excerpts from works -- some of which found a place in the repertory, many of which did not -- that Jamison commissioned or revived during her tenure. The three new dances include Ronald K. Brown’s “Dancing Spirit,” created as a tribute to Jamison and sharing the title of her 1993 autobiography. Also on the bill is Jamison’s latest work, “Among Us,” in which she reveals a new side -- enlargements of her own paintings are a crucial part of the set. Also new is “Uptown,” the first work for the troupe by Matthew Rushing, its exemplary senior male dancer. And for a season that recognizes Jamison’s respect for, and expansion of, the Ailey legacy she inherited, she has revived “Hymn,” her 1993 full-company work that incorporates Ailey’s own words and dancers’ deeply personal memories of him.

When Ailey died Dec. 1, 1989, Jamison -- who had been the company’s leading dancer from 1965 to 1980, creating several iconic Ailey roles -- became artistic director on Dec. 20. So her exact 20th anniversary fell while the company was in the midst of its recent 40 New York performances -- a hugely popular season that has become as much of a holiday dance tradition in the city as “The Nutcracker.” Between the onslaught of premieres, multiple casts for every work, dancer injuries and substitutions, she might not have taken note of the specific date. But in curtain speeches, television interviews and award presentations, she never forgets the company’s roots and the specific sense of purpose with which Ailey imbued his dancers.

“I am a continuation of what Alvin started. And what I wanted to do was broaden it -- make it bigger, and certainly not have anyone forget who this man was, what he has done for the world of dance -- what a great swath of intelligence and beauty, and a different way of looking at movement, and sharing the stage. He just made a big pathway for all of us to pursue our individual and collective goals.”

Jamison led the company through considerable growth, to a remarkable level of stability, thanks to extensive touring. She will be leaving it in strong shape for her successor when she steps down in the middle of next year. The Ailey organization encompasses not just the main company and Ailey II, its junior ensemble (which also tours widely), but a school with a broad range of classes for both aspiring professionals and recreational dance students. The gleaming eight-story building, with its huge windows inviting the public to look in, includes a black-box theater and enough studios that the Ailey Extension was launched, offering classes (such as African dance and yoga) that keep the hallways bustling with activity. It’s a logical embodiment of Ailey’s oft-cited dedication to “bring dance to the people” and foster inclusiveness.

The company has an unusually high profile and a level of recognition that most concert dance troupes can only dream of. Soon after the presidential inauguration, the entire Obama family was present when the troupe performed at the Kennedy Center last February. The company pulls in a popular audience that might consider other dance performances too rarefied but make a point of seeing Ailey every year. The seemingly eternal lure of “Revelations,” the work Ailey choreographed to spirituals in 1960 that closes the majority of the company’s performances, has given the company a signature work that resonates with audiences. “We can -- and do -- close with other pieces. Do you know how many complaining letters I get on my desk when we do?” Jamison said.

While retaining that and other repertory touchstones, Jamison has ranged far and wide in her choices of those who create new work with the company. “I wanted to bring in European choreographers. I certainly wanted to bring in as many African American choreographers as possible, and people of color, because their song still wasn’t being sung.”

She has reached out to strongly individual figures such as Garth Fagan, Donald Byrd and Alonzo King, and brought in works by Twyla Tharp and Lar Lubovitch. She has at times focused on female choreographers, and also opened the doors to some whose gimmicky work disappeared after a season. She has certainly broadened the dancers’ experience, but only rarely has a choreographer established an ongoing connection with the company and truly enriched its repertory.

Brown, whose fluid movement incorporates many elements of traditional African dance, has done that, making four works for the company starting with “Grace” in 1999. “Dancing Spirit,” his most authoritative and refined to date, alludes to the company’s history and personalities, and received considerable critical acclaim at its December premiere. “Ronald K. Brown is a must,” Jamison asserts. “The work that he does is so important, because there is a freedom about a technique that says something about being American, being African American, having a root of Africa, and also being open, very accessible and spiritual.”

The company has never had a resident choreographer, although Jamison mentions that Ailey once envisioned Ulysses Dove -- a company member whose works have found an ongoing place in its repertory -- in that role. But both died prematurely, and it never happened. “I never thought that I should find a resident choreographer. Maybe the next artistic director will think that.”

Jamison speaks in upbeat terms of the impending transition. “I feel fine, I feel terrific. I will certainly still be attached to the Ailey company. I’m just giving somebody else the title. Only two people have run this in 50 years, so this is a gift. And I’m passing this gift along.

“I feel wonderful, and hopeful.”

She explained the timing of the announcement of her departure, which happened in 2008: “I wanted three years in advance to be able to choose people -- to be able to really research this, and work with my board, with [associate artistic director Masazumi] Chaya and [executive director] Sharon [Luckman]. I’m making the decision -- but I never do anything in a vacuum.

“I’m looking for a unique perspective -- in terms of how they’re going to maintain and soar the company for the next 50 years.”

Her successor, she said, will need “to have that unique chord that understands the past; to face the present and do -- absolutely, with a brave heart that is courageous and steps out there, and sees what other people aren’t seeing yet -- take those chances.”

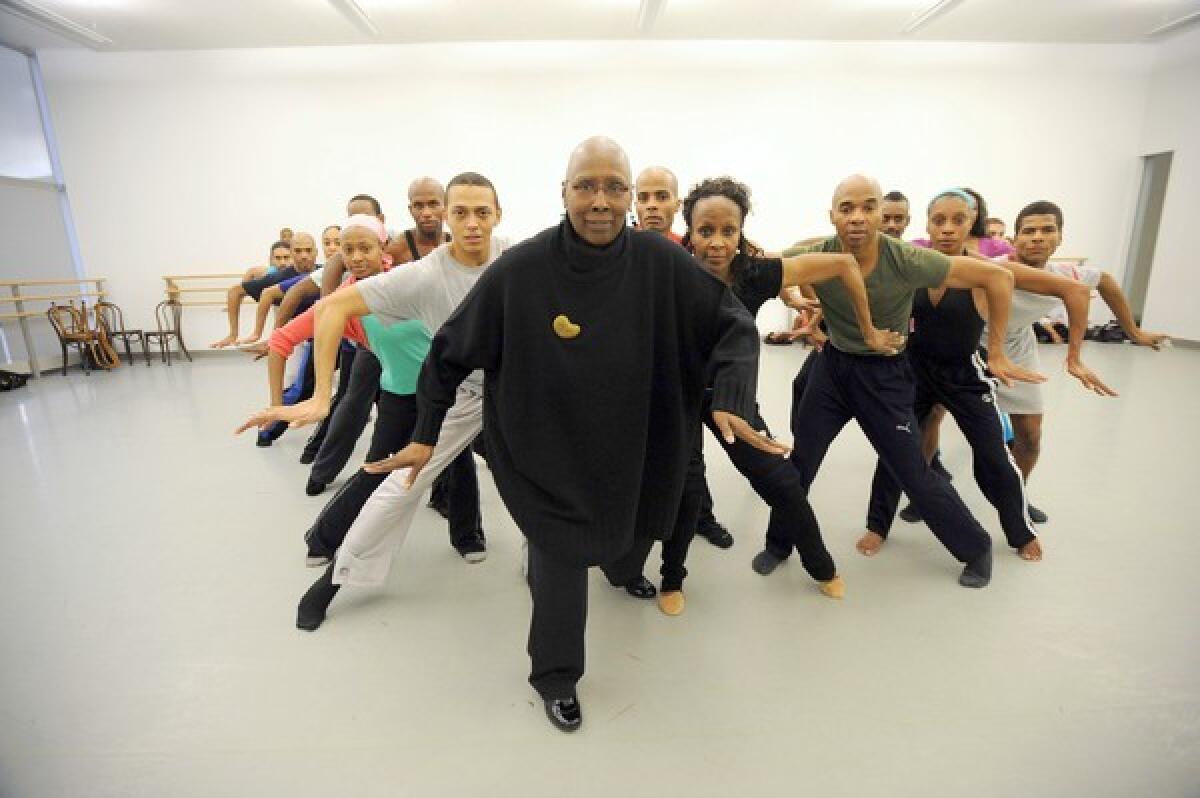

With that, it was time for her to leave her desk with its ringing phones and shift gears. She swept magisterially toward a large studio, where the cast of “Among Us” awaited her eagle eye and pointed comments as it prepared her latest work for the tour.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.