As Myanmar rights official, an Elvis impersonator sings different tune

It was 1967 when U Win Mra, Burma’s most successful Elvis impersonator, relinquished his dream of a singing career.

As a teenager, he had twice won nationwide contests for mimicking the king of rock ‘n’ roll. Three songs he recorded for the national broadcasting service became radio hits.

But in Burma, a socialist dictatorship that was steadily sliding into diplomatic isolation, Win Mra saw no future for himself onstage singing Western music.

Reluctantly, he says, he chose a more sensible career in the Foreign Ministry.

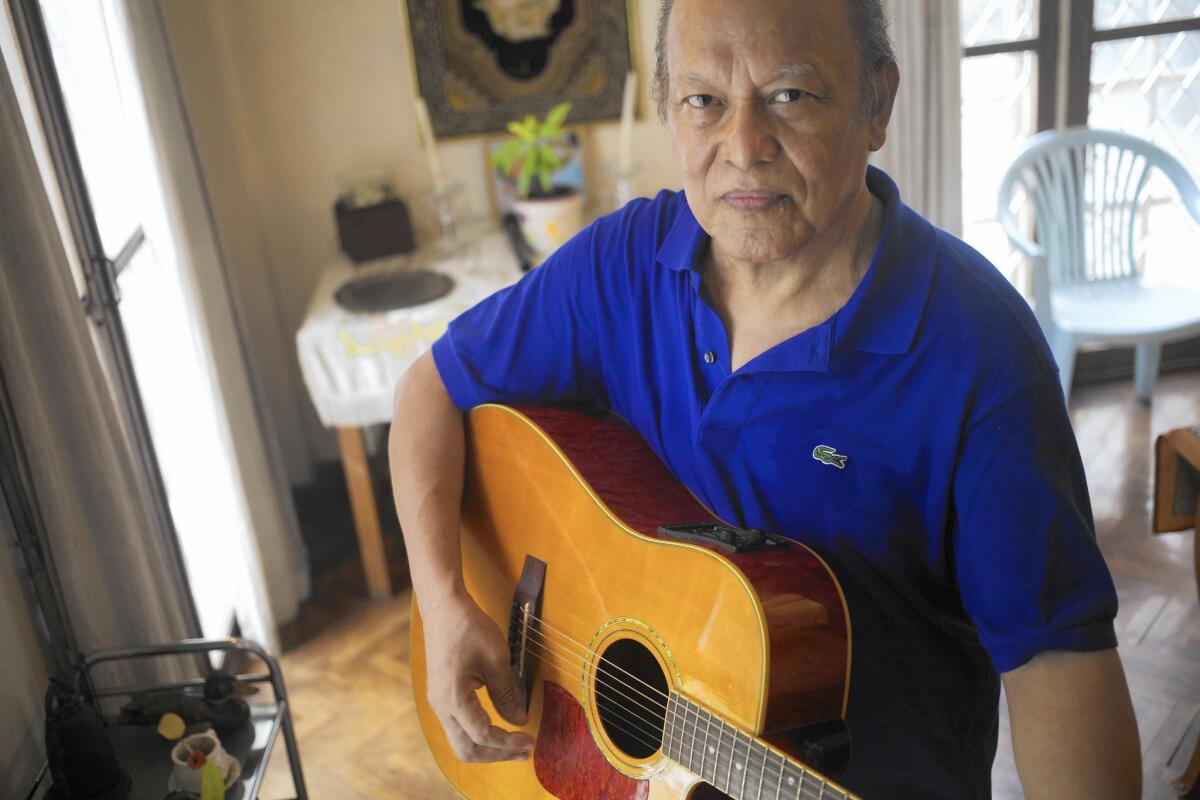

Nearly five decades later, the crooner still entertains visitors with renditions of “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Love Me Tender,” but his day job is heading the National Human Rights Commission in Myanmar, as the country is also known today.

“If it were up to me I would retire and sing Elvis songs in my home all day long,” Win Mra says in an interview in his living room, filled with keyboards, guitars and photos of him meeting heads of state.

“I can’t shake it in my longyi [the traditional Burmese sarong] like I used to in my tight trousers.”

A good Elvis impersonator, he says, isn’t so much a technically proficient performer as one who excels at embodying a character. Critics say Win Mra, in his role as human rights commissioner, has employed similar skills of artifice and illusion.

::

The country’s first ostensibly independent rights body was formed by President Thein Sein in 2011 as part of a closely watched transition toward democracy after decades of military rule. Its creation was widely viewed as a remarkable turn of events. But even as the United States and others have offered qualified praise to the country’s leadership, the human rights commission has come under fire for lacking autonomy, ignoring violations and, in some cases, contributing to further abuses.

Commissioners are appointed and paid by the president, a former general, and have no authority over government bodies or the military. The deputy head of the commission, U Zaw Win, former chief of corrections for the military government, oversaw a particularly abusive period in Myanmar’s notorious prisons.

Describing the commission’s independence as “evolving,” Win Mra defends Zaw Win, saying he was uniquely qualified to reform the correctional facilities.

The commission published a report on conditions at Yangon’s Insein Prison in 2011 that acknowledged for the first time that political prisoners were being held there, but glossed over reports of poor living conditions and documented cases of torture, according to Human Rights Watch, the International Committee of the Red Cross and other groups.

Win Mra dismisses such complaints. He tried the prison’s lentil curry during an official visit, he says, and found it “very tasty.”

During the interview, he pulls out his guitar to play Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues.”

“You know, our Insein Prison is not the worst in the world,” he declares, briefly interrupting his performance. “That is Abu Ghraib.”

::

The commission’s shortcomings are emblematic of the broader transition in Myanmar, which is widely seen as faltering as the military retains significant power with elections scheduled for the fall. A quasi-civilian government led by former generals has cracked down on ethnic minorities, student protesters, journalists and other dissenters, with scant objection from the commission.

Critics say Win Mra’s long career as a protector of the military rulers’ interests makes it difficult to take him seriously as an advocate for human rights.

“He’s not an independent promoter of human rights in Burma as he should be, but a sinister glove puppet of President Thein Sein to burnish his questionable commitment to promoting rights and delude the international community that his government is serious about these issues,” says David Scott Mathieson, a researcher with the New York-based Human Rights Watch.

Before being appointed to the commission, Win Mra was Myanmar’s representative to the United Nations, where rights groups called him the army’s foremost apologist. He describes his role as an “international whipping boy” for what was then a pariah state.

He previously served as ambassador to Israel, Cuba and France and as interpreter for nearly every major Myanmar head of state, including former Senior Gen. Than Shwe, the last military ruler before the democratic transition.

Win Mra says there is no point in delving into the government’s past behavior; he was simply doing his job as a civil servant when he served the leadership. Furthermore, he says, he doesn’t read critical reports by outside groups because they lack objectivity.

“I can’t learn from criticism; it doesn’t help at all,” says Win Mra, “Can you tell me any country that is free of violations of human rights? None are free. Then what is the point of criticizing?”

When a civilian from the Kachin ethnic minority complained to the commission this year that soldiers had unlawfully shot and killed his daughter, his letter was forwarded to the army, which sued the man for filing false charges.

The commission has acknowledged that it will not investigate abuses in conflict zones, in particular those reportedly perpetrated by the military.

“We do whatever we can,” Win Mra says. “Why would people expect us to do more than what we have the authority to do?”

::

When asked what Elvis Presley song best describes Myanmar’s democratic transition, Win Mra has a ready answer: “Loving You.”

“In a country that is changing democratically, in human rights and every way,” he explains, “you have to embrace the human rights of every person.”

Yet the commission has taken a hard line on the issue of Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims, a minority of about 1 million people who suffer from systematic government discrimination. Thousands of Rohingya have fled prison-like camps, boarding dangerous boats bound for Malaysia, often drifting at sea for weeks because neighboring countries refuse to allow them ashore.

The Myanmar government labels the Rohingya as Bangladeshis who entered the country illegally, even though many families have lived in Myanmar for generations. They are denied citizenship, voting rights, freedom of movement and healthcare.

Even after the refugee crisis made international headlines in May when thousands of Rohingya were stranded at sea, the commission absolved the government of responsibility.

“This is nothing to do with a human rights violation, because these people pay thousands of dollars to get into the boats,” Win Mra says, blaming transnational networks that traffic migrants to Southeast Asia.

Win Mra is a member of the Buddhist Rakhine ethnic group, which, like the government, doesn’t recognize the Rohingya. He refers to the Rohingya, who mainly live in Rakhine state, as “strangers.”

“As human beings,” he says, “we have the right to food, health and other human rights, but when you claim yourself as a Rohingya, that’s a different issue.”

Paluch is a special correspondent. Times staff writer Shashank Bengali in Mumbai, India, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.