Column: The Republican tax plan is an arrow aimed at blue states like California

Government budgets are political documents, as the adage goes, but tax proposals are even more so.

Nothing illustrates this as well as the House Republican tax bill released Thursday. It’s essentially a handout to big business and the rich, which are the Republicans’ chief patrons, and an attack on Democratic-leaning states and their taxpayers. Californians, along with residents of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Illinois, should lay in a supply of antacids now because they’re going to be feeling severe indigestion as this product moves through the congressional alimentary canal.

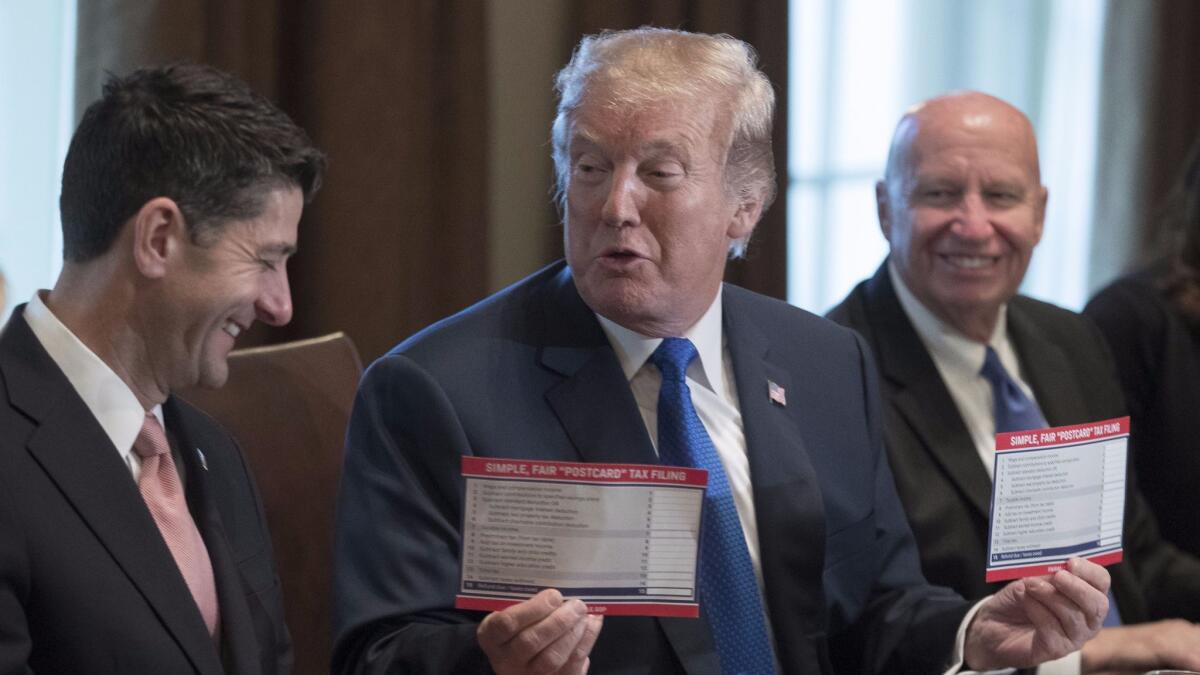

Even if the 429-page tax bill released Thursday by the House Ways and Means Committee reflected some sort of political consensus on tax policy, it would be subject to weeks of textual and mathematical parsing, and it’s certain to be a moving target.

States will have two choices. They could either cut back on services that are broadly shared ... or find revenue sources that tend to be more regressive.

— Chye-Ching Huang, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Nevertheless, its general thrust is crystal clear. The bill would eliminate a host of tax breaks, including some enjoyed by middle-income taxpayers, in order to deliver the largest tax cuts to the wealthy and corporate shareholders. (These are overlapping categories.)

GOP rhetoric asserts that almost all Americans would get a tax cut, but that’s misleading. Whether low- and moderate-income households get the vaunted benefits of such provisions as the doubling of the standard deduction is dependent partially on the size of their families, since the tax plan eliminates the personal exemptions and replaces it with a roster of child credits. It’s by no means certain that these provisions won’t net out to working families’ disadvantage.

In any case, the wealthy receive a disproportionate share of all the tax cuts in the bill. The top 1% of income earners in the U.S., who collect about 19% of all income, pay about 38% of federal income taxes. But they’d receive as much as 80% of the tax benefits in the bill, according to a preliminary estimate released in September by the Tax Policy Center. (Republicans attacked the analysis at the time as premature because details of the GOP plan hadn’t been finalized, but the final version looks very similar.)

What may be most important about the House bill is its effect on state and local budgets. The bill would eliminate federal tax deductions for state and local taxes except property taxes, on which the deduction would be capped at $10,000 a year. Republicans will try to sell this to the unwary as trimming a tax break enjoyed mostly by the wealthy. But the change is likely to increase financial burdens and result in reduced services for moderate- and low-income Americans.

In California and other states reliant on state income taxes, eliminating the deduction would increase resistance to tax increases, especially among politically influential high-income taxpayers. To maintain services, states would have to collect more revenues from sources such as sales taxes and user fees, which fall disproportionately more on moderate- and low-income residents.

“States will have two choices,” says Chye-Ching Huang, a federal tax expert at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “They could either cut back on services that are broadly shared in the community or find revenue sources that tend to be more regressive.”

That’s not to say that shift would be easy: Consider the public discontent with the 12-cent-per-gallon gasoline tax that went into effect in California on Wednesday. That’s effectively a user fee placing the cost of maintaining the state’s roads most directly on the shoulders of drivers, even though the benefits of maintenance are felt throughout the economy.

California’s ability to shift revenue sources to meet basic needs already is limited by Proposition 13. That 1978 ballot initiative sharply cut property taxes, which then provided 60% of the funding for local school districts. Today, K-12 districts are reliant on the state for nearly 60% of their funds. That’s one way that constraints on the state budget could trickle down to local services.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities points out that it’s not only states reliant on income taxes that could suffer from eliminating the deduction. Because federal taxpayers can choose whether to deduct income taxes or sales taxes, states that rely heavily on the latter could be affected. That includes Texas, the home state of Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady. Since Texas has no income tax, more than 2 million tax-paying families, or 18%, deducted about $4.8 billion in state and local sales taxes in 2015, according to the center. Brady’s bill would take that deduction away.

Still, the size of the state and local tax deduction generally tracks the political leanings of the states, with states that lean more heavily Democratic tending to have the highest taxes and, consequently, the largest concentration of deductions. (Kevin Drum of Mother Jones mapped the relationship graphically here, using Clinton-Trump vote margins in the 2016 election as a proxy.)

One could call this a coincidence, but it isn’t really; Democratic voters tend to be more open to public services, which require tax funding, and Republican voters are happier to spend less and get less.

The weightiest benefits in the tax plan all are aimed at the wealthiest families. These include elimination of the alternative minimum tax, which ensures that wealthy households with certain tax breaks still pay a significant share of taxes, and the repeal of the estate tax. The latter would be entirely repealed by 2024, and sharply reduced in the meantime by doubling the exemption for estates to $22 million from the current $11 million (for couples).

The wealthy also get to keep not only the preferential tax on capital gains but also the step-up in value of capital assets upon their inheritance by the next generation. As USC tax expert Edward Kleinbard is fond of repeating, the capital gain tax is our only voluntary tax: It can be deferred indefinitely simply by not selling the capital asset; when the asset is inherited, its value is reset to whatever it’s worth at that moment, and — Presto! — all the embedded tax liability is extinguished forever.

As we’ve observed before, the capital gain tax break is so enormously valuable to the rich that they’re happy to give up any number of other breaks in order to keep it. Much has been made of the GOP’s plan to cap home buyers’ deductions at the interest on mortgage balances of $500,000, compared with the current limit of $1 million; the truth is that the mortgage deduction is worth comparative pennies to the highest-income households. In 2015, the average mortgage interest deducted even by taxpayers with more than $10 million in income was less than $25,000. The average net capital gain they declared was $14.5 million. The difference between the ordinary and capital gain tax rate on that sum would create a tax benefit of nearly $2.3 million.

Who will lose? Moderate- and low-income residents of blue states and red states alike. None of the tax breaks in this bill will do anything for economic growth. “Boiled down to the basics,” writes Howard Gleckman of the Tax Policy Center, “it is a mid-sized tax cut aimed mostly at businesses and their owners.” He advises not to be snowed by the claim that it’s good for everyone: “Many middle-income households are likely to pay more under this plan, not less.”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.