Californians compete for a rare prize: a blue-collar union job paying up to $200,000

If Cynthia Byington wins her version of the lottery, she will probably have to wait a decade to claim her prize. But Byington doesn’t mind, because the reward is a shot at one of the rarest lifelines left for working-class Americans: a unionized blue-collar job.

In February, for the first time in over a decade, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union will raffle off thousands of part-time gigs working at Los Angeles-area ports. The slots don’t come with benefits or steady hours. But eventually, after putting in years at the docks, some of those part-timers may earn the chance to become unionized longshoremen, who can make as much as $200,000 per year.

“You get full benefits your entire life. Even if it’s not ‘til I turn 90, it’s worth it,” Byington, 53, said.

You get full benefits your entire life. Even if it’s not ‘til I turn 90, it’s worth it.

— Cynthia Byington

The 2,400 names drawn in the raffle will become “casual” longshoremen.

Although they perform the same work as union members — loading thousands of containers on and off massive cargo ships to keep the ports running on time — they work far fewer hours. And the wait to receive full union benefits can stretch over a decade.

The average casual worker who showed up for weekly shifts earned nearly $31,000 in 2016, according to data from the Pacific Maritime Assn., which represents the shipping companies and terminal operators that employ the dockworkers. Full-time union members get paid $161,000 on average, but those with seniority can earn tens of thousands more.

Today, there are part-timers who have been waiting 13 years to get into the union. But the PMA said that for now, there are no firm plans to elevate any of them.

Hundreds of thousands are expected to have applied for the new casual slots, the PMA said. Scores of Southern Californians rushed to post offices and postal stores across the South Bay in January, buying up the 4x6-inch blank cards required to enter the raffle.

At the Postal Annex, a tiny storefront about five miles from the ports in San Pedro, owner Patrick Meehan could barely take a breath without getting a phone call about the lottery. He said hundreds of people streamed into his store in the three days before the deadline hit in late January.

The massive interest in the longshoremen’s lottery is a sign of just how desperate Americans are to gain even the most tenuous ground toward a stable, high-paying career working with their hands.

“It says a lot about the state of our current labor market,” said Ken Jacobs, chairman of the UC Berkeley Labor Center. “There are a dwindling number of blue-collar union jobs where people with just a high school education can make a good living.”

Fewer than 14% of workers in manufacturing, construction and trucking belonged to a union in 2015, down from nearly 40% in 1973, according to a database of Census data compiled by economists from Trinity University and Georgia State University.

That’s what propelled Byington to put her name in the running.

“It’s once in a lifetime,” said Byington, who lives in a mobile home in Wilmington. She has seen longshoremen and women buy houses and put their kids through college on their union-won paychecks. Another friend recently got a full set of teeth implants, thanks to union-provided dental care.

“If you say someone is a longshoreman, it means respect, even if they are a little spoiled,” Byington said.

Earning that title, and the respect that comes with it, takes longer than ever.

In the 1990s, longshoremen would spend three to five years freelancing before they got elevated onto the rolls of the ILWU, according to interviews with more than a dozen current and former casual workers. But then the recession hit, trade faltered, and the PMA temporarily stopped hiring union members.

The ports are using more automated machines, which is part of the reason the union workforce hasn’t grown much. In 2016, the Port of Los Angeles processed 17% more container traffic than in 2005, but the number of full-time union longshoremen had increased by only 3.5% over that period.

Longshoremen also say employers have been relying more and more on part-timers.

“The PMA, terminal employers and ILWU work together to maintain a balanced approach on the number of registered workers needed at the ports,” said Wade Gates, a spokesman for the PMA.

Craig Merrilees, a spokesman for the union, said the union has traditionally pushed to get more full-time positions, but the dockworkers’ bosses are reluctant. The last time the PMA added full-time union members to the payroll was in 2012.

“Generally speaking, the employers would like to see more casual workers earning a little less pay,” Merrilees said.

Mario Huerta says he has been working part time for 10 years at the docks, desperately trying to amass enough experience to become a union longshoreman.

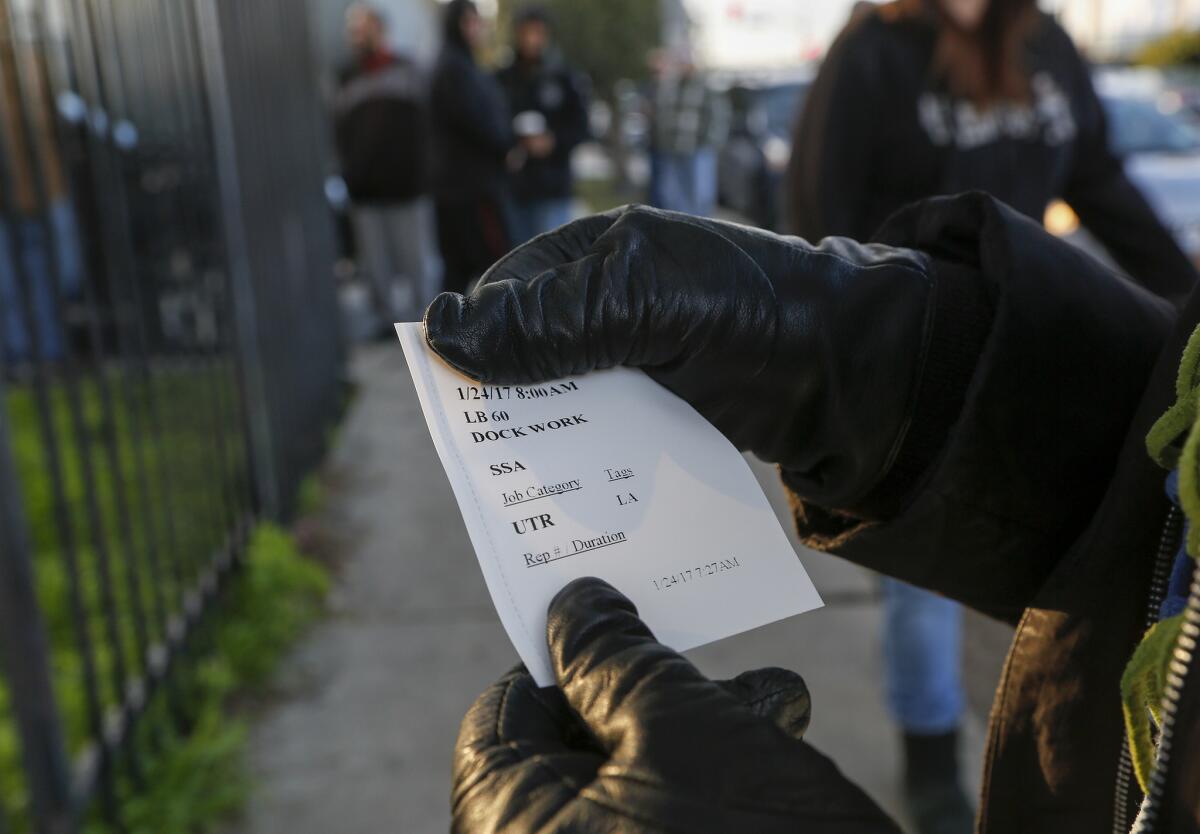

Huerta and other casuals show up around 6 a.m. at a dingy dispatch hall and wait to hear if their number gets called for one of three shifts at the port. If they don’t get called up in the morning, they can return around 4 in the afternoon for the next round of work opportunities.

On good weeks, a part-timer will manage to nab two to three eight-hour shifts, casuals said.

After driving 60 miles to Wilmington from his home in Riverside on a recent Friday, Huerta was assigned a shift that would likely involve securing containers to a ship deck.

“Sometimes I get work two or three days a week. Sometimes it's only one day a week,” Huerta said, standing in the rain just outside the building where casuals go to get dispatched. He has no idea when the unsteady work will turn into something long-term.

“How close am I to being elevated? Nobody seems to know,” he said. “At least today I have work.”

Several others who failed to get work that day said they felt as if they’re being kept out of the union for as long as possible so that the shipping companies can avoid hiring more highly paid, full-time longshoremen.

Sometimes I get work two or three days a week. Sometimes it's only one day a week

— Mario Huerta

The casuals all cobble together odd jobs on days they can’t find work at the docks, including gigs in construction, landscaping and as security guards.

Chris Grove, 39, has spent 13 years reporting for duty at the casual hall and says the instability of the work “tore up” his marriage. Grove, who comes from a long line of longshoremen, including his mother, says the work at the ports was steady and continuous until the recession of 2008-2009.

“I was able to put groceries on the table and keep the wife happy,” he says.

After the financial crisis, though, his name barely ever came up for shifts. So he got a second job, installing security systems, and then another, installing satellite dishes for DirecTV. He put his name on a list to join an elevator construction union and became a bouncer and then a security guard at a cannabis collective. He even got paid to register voters.

The work was unpredictable, he says, and his paycheck was so much thinner than it once was.

Grove still shows up for work at the casual hall some weekends, but now he’s more focused on his day job: In 2014, after waiting for eight years, he was admitted into the International Union of Elevator Constructors and makes good money with a full slate of benefits.

Times staff writer Ronald D. White contributed to this report.

Lead photo caption: Part-time casual longshoremen outside the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Casual Longshore Dispatch Hall in Wilmington, where some lucky workers will nab a shift. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)