The Craftsman reawakened

The rescue of the Blacker House, Pasadena’s grandest Craftsman, is less a fairy tale than a detective story. It even includes a “crime scene” — at least, that’s how locals describe what they call “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” the night the house was stripped of valuable windows, doors and lighting fixtures by a Texan known as “Black Bart.”

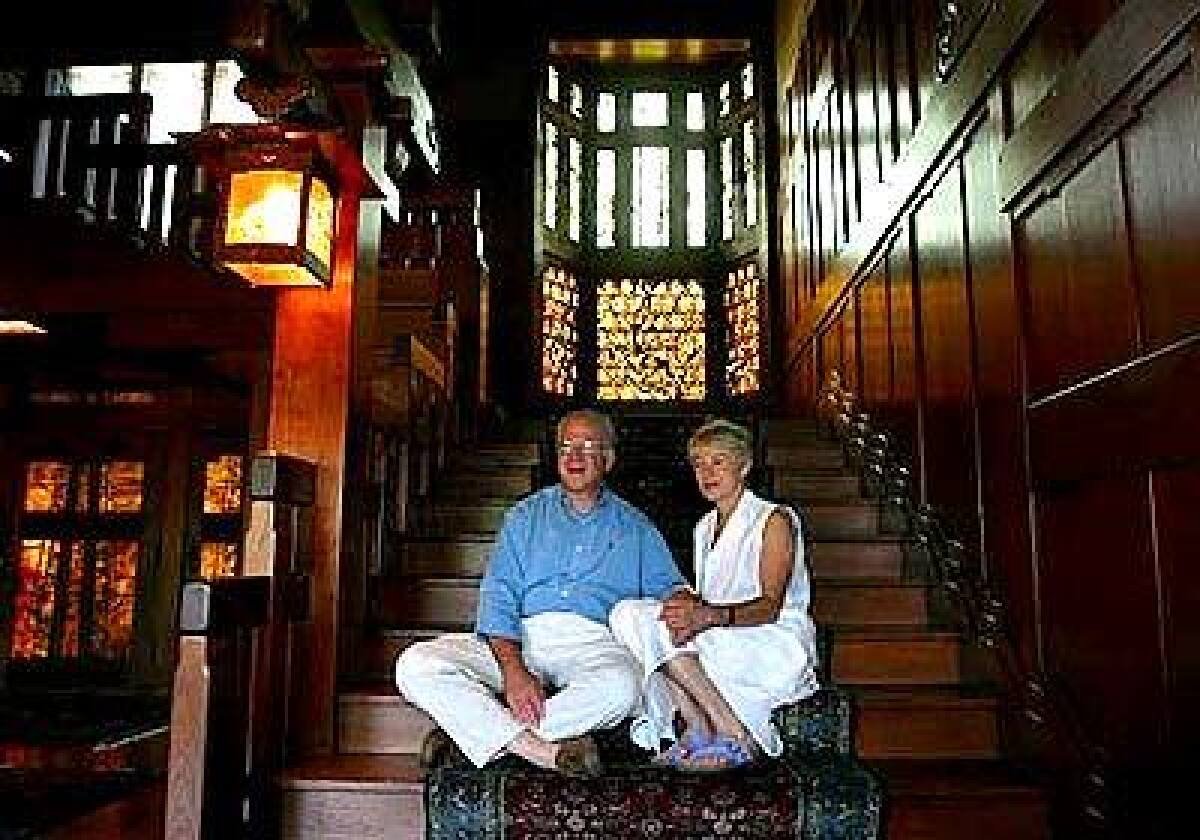

The latest owners, Ellen and Harvey Knell, have mined the Blacker’s history for clues as they fastidiously restore the once-grand house built in 1907 by renowned Arts and Crafts architects Charles and Henry Greene. They also have charged themselves with remaking items sold by previous owners out to make a buck off of architectural history.

FOR THE RECORD: Blacker House —An information box with an article about the Blacker House in last Thursday’s Home section gave the wrong phone number for an upcoming charity event. The correct number for tickets and information is (626) 685-4455.

Even before closing escrow a decade ago, the Knells began planning the resurrection of the approximately 12,000-square-foot house, intending to reproduce — or recover — the original art glass, lights and furniture that had been removed by various owners. They also hoped to reacquire the rest of the land that once made up the original 5.1-acre estate in Pasadena’s Oak Knoll neighborhood.

A decade later, they’re still on the case. “We’re really just taking it piece by piece,” said Harvey

Knell, president of a capital management company.

Master craftsman Jim Ipekjian became their chief investigator. He traveled to museums and the homes of private collectors across the nation to study, then replicate, fixtures and furniture that once belonged to the Blacker House.

The end result: except for a few remaining pieces of furniture, a fully restored house that shows little evidence of its six decades of neglect and mistreatment.

Meanwhile, renovation continues on the pergola and carriage house, which the couple persuaded neighbors to sell in October. Using photocopies of original blueprints and Blacker family photographs, the Knells are re-creating the palm-dotted back vista, which once had an allée of trees, a fountain and a pond. “This is the granddaddy of all restorations,” said Randell Makinson, a USC architecture professor emeritus and authority on Greene & Greene architecture.

Santa Barbara landscape architect Isabelle Greene, granddaughter of Henry Greene, is designing the garden, soon to feature a rambling lawn, roses and large flowerbeds. Ipekjian and his two sons will spend the summer rebuilding the pergola. Painter and colorist Brian Miller, who also worked on the Gamble House, is set to finish the carriage house by fall.

“The Blacker House is really the ultimate Greene & Greene,” said Claire Bogaard, who helped start Pasadena Heritage, the city’s historic preservation group, in the late 1970s. “It really is a treasure. Houses like this one bring value to the entire community.”

Makinson had doubted whether the Blacker House would ever be saved. “The house was going downhill faster than you could believe. I figured there would never be anyone with the integrity, intelligence and the funds to pull it all back together,” he said. “And then Harvey and Ellen came along.”

The Knells had admired the house since the early ‘80s, but didn’t stand in line to buy it until 1994, when they bought it for an undisclosed sum.

“We bought it with a lick and a prayer,” Ellen Knell said.

One thing quickly became clear: The house had been respected in its early years, with no structural alterations.

Robert R. Blacker, a Michigan lumber magnate who retired to Pasadena, commissioned the 18-room structure early in the 20th century. He had a keen appreciation for the imagination of the Greene brothers and embraced the organic, handcrafted Craftsman look.

For the Greenes, decorative arts were a natural extension of their architectural design. With the help of a dedicated team of master craftsmen, they filled their houses with warm woods, art glass, earth-toned lights, simple metalwork and custom wood furniture.

The Blacker House was one of seven “ultimate bungalows,” rambling, wooden homes that the Greenes built between 1907 and 1909. The masterpieces include the Thorsen House in Berkeley and the Gamble House in Pasadena. Although each house was uniquely handcrafted, the Blacker was the largest — and some believe the most beautiful — of the Greenes’ “wooden wonders.”

“They took the international Arts and Crafts movement to new heights,” said Makinson, who has written several books on the Greene brothers’ work.

Henry Greene, who became the house’s caretaker after Robert Blacker’s death in 1931, urged Blacker’s widow, Nellie, to ensure that the house would be properly cared for after her death.

A little more than a year after Nellie’s death in 1946, five businessmen banded together to purchase the estate and subdivide the land into seven parcels. One by one, the properties were sold, along with much of the Charles Greene-designed furniture by the first Blacker House buyer — at a giant yard sale.

Over the years, many of the Blacker’s owners either neglected it or imposed one stylistic change after another on it. Then, in 1985, Barton English — a.k.a. “Black Bart” — bought the house for $1.2 million, less than the cumulative worth of the art glass and fixtures if sold on the open market. English had a final request during escrow, Makinson says: The curtains must be left on the windows.

In the dark of night, preservationists say, his crew carted off the front door, a half-dozen stained-glass windows and 53 light fixtures.

At auction, some lamps fetched $100,000; two dining room chandeliers went for a half-million dollars each. Though his actions were in no way illegal, they drew the wrath of preservationists, who as a result pushed for laws to monitor future changes in historic sites. Up until this point, the home’s various owners had violated no laws or historical society’s edicts.

Bogaard, who forced the city to stop English from ripping out the house’s wood-paneling — keeping vigil outside to make sure he followed orders — vowed that the community would never again suffer such a monumental loss.

When they finally got their chance to restore the house, the Knells assembled a team of artisans, scholars and craftsmen, including Ipekjian, who had produced pieces for Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House and worked other Greene & Greene homes.

First, the Knells wanted him to focus on the exterior — untreated redwood that had been installed two decades earlier had turned black. As the crews removed the rotted wood, Ipekjian saw a green spot a little bigger than a pinhead on one of the shakes. He became certain that the dark speck was, in fact, green stain. After more analysis, the Knells made the final call: The shakes would be a deep shade of moss green instead of black.

Exterior timbers, rafters and trim were also returned to their original color — medium-dark brown. Windows and doors were coated with a light natural finish. After more than a year, the outside was finished.

According to Makinson, the attention to detail meant that for the first time in more than 50 years the exterior of a Green & Greene house could be seen as it was originally built.

Ellen Knell networked with museums, antiques dealers, auctioneers and gallery owners around the country to purchase or replicate the art glass and furniture that had disappeared. She put together a list: The stained-glass front doors were in the Dallas Museum of Art, some furniture was in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and one of six living room chandeliers was found at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Many other items were in the hands of private collectors.

The Knells bought back a several of the missing windows from private collectors. Everything else would have to be remade. Over seven years, Ipekjian and his team of craftsmen re-created all 53 of the missing lights and 25 pieces of furniture. His reproductions of Charles Greene’s pieces are so exact that he needed to sign and date them so they wouldn’t be confused with the originals.

Ipekjian uncovered the plans for the structure at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural Library three years ago. Recently, Harvey Knell took a copy of the original blueprint to the city of Pasadena, to obtain a permit to rebuild the pergola. At first, a city official questioned whether such old plans would meet new standards. Knell told him to recheck the code books. “We fall under the historic code,” he said. The man signed off on the project.

Says Ipekjian with a laugh: “How can you argue with Greene & Greene?”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Step inside

Harvey and Ellen Knell often open the Blacker House for charity events. The next gathering, at 4 p.m. Sept 19, will benefit the Southwest Chamber Music ensemble. Tickets, which cost $50 and include a CD, should be purchased before Aug. 19. (626) 685-4455.

*

A family connection

The landscape architect who is restoring the gardens at the Blacker House has the right last name, and lineage, for the job.

Isabelle Greene recalls walking along the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains with her grandfather, famed Craftsman architect Henry Greene.

“He was an old man, and I was a teenager,” said Isabelle, now 70. “His architecture career was way, way past. We didn’t talk about that.”

Instead, they conversed about another mutual love: nature.

Those early discussions along the rugged, flower-covered hillsides inspired Isabelle to pursue a career in landscape architecture, which she has practiced for nearly four decades.

She is faced with a hugely sentimental task: re-creating the long-ago destroyed gardens at the largest Craftsman built by her grandfather and his brother, Charles Greene.

The latest owners of the house had met her through mutual friends at the Gamble House, another Greene project. Isabelle went to work in January drawing up landscape plans based on old photographs of the yard before the property was subdivided in the 1940s.

The Santa Barbara-based professional is also doing a little improvising by choosing old-fashioned flowers — foxgloves, yucca plants and lilies — in honor of her grandfather, who often drew inspiration from the outdoors when designing post-and-beam homes.

“He was a wonderful, wonderful person,” Isabelle said. “He was gentle and good-humored and very supportive . If I’m ever feeling overawed, I ask myself, ‘What would my grandfather like?’ Then I’m off and running.”

— Tina Daunt