Free Iraq Forces Hope to Fill Vacuum

They’re butchers, bakers and fast-food makers with Russian rifles and mismatched uniforms. They hail from Arizona, Syria and Norway and they’re here to forge a new Iraq.

As the long-feared armies and security tentacles of the Saddam Hussein government disintegrate or melt away, the U.S.-funded Free Iraq Forces hope to fill the vacuum and become the rump of the nation’s new army.

They have a ways to go.

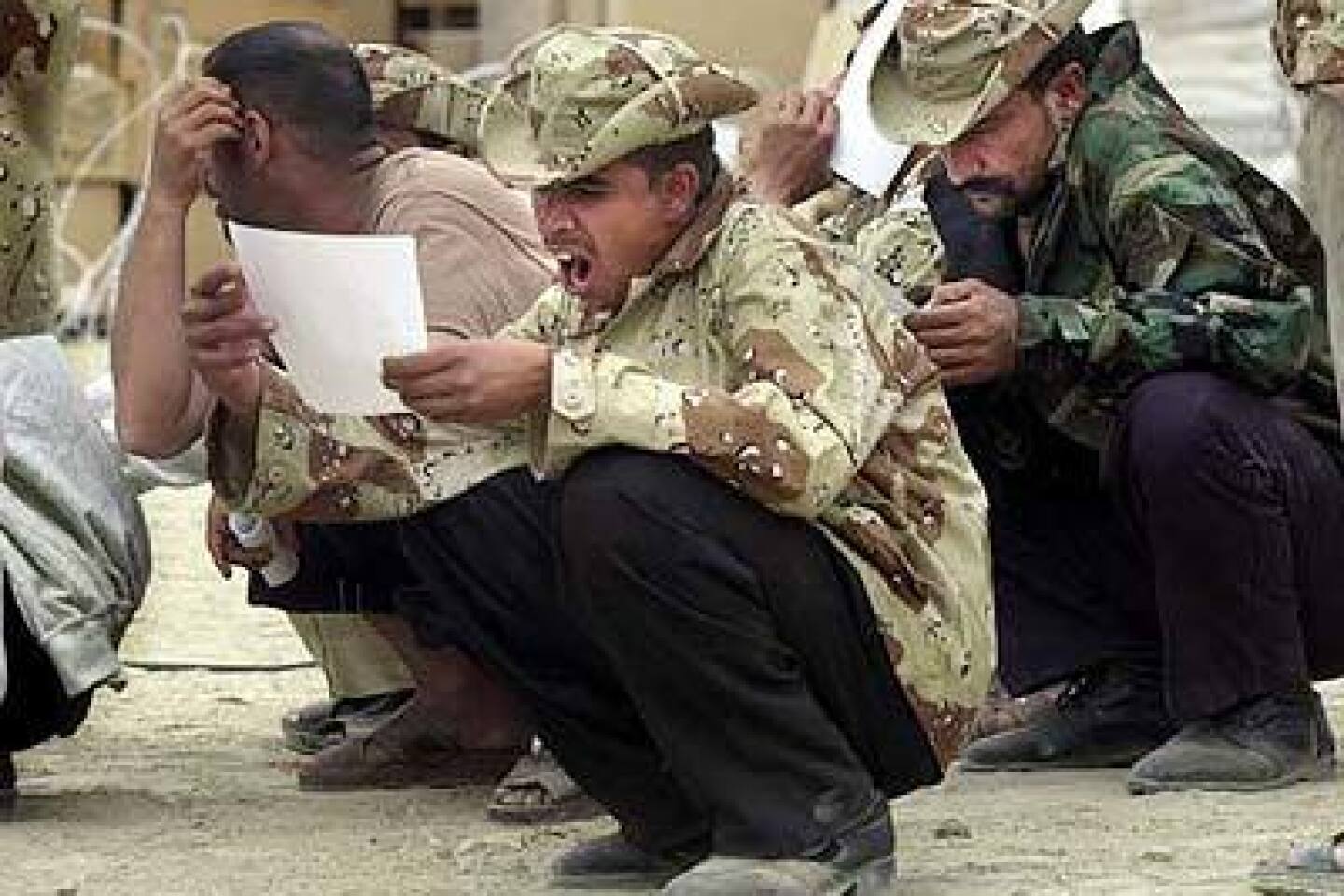

At the Air Base 71 Imam Ali Camp outside Nasiriyah, several hundred men line up for morning roll call after their commander barks at them three times to get a move on. Some have guns raided from the Iraqi military, others don’t. Many of their pants don’t match their brown “chocolate chip” camouflage shirts. Several wear sandals in shades of black, blue and bright orange and virtually all chat away happily in their wavy lines.

“They’re not the Wermacht,” said Zaab Sethna, advisor to Iraqi National Congress head Ahmed Chalabi, who is camping out in one of the base’s partially destroyed buildings to show his support for the troops. “But their motivation is very high.”

The 700 Free Iraq troops in Nasiriyah are growing steadily as volunteers besiege the gate. Abdul Hammid Husona, a 36-year-old local dignitary, waits at the gate claiming to represent 50,000 villagers interested in signing up.

Most already in the ranks say they’re motivated by freedom, patriotism and a desire to vanquish Saddam Hussein. But the clothes, U.S.-packaged meal rations and promise of $150 a month represent tempting targets in a devastated economy.

“We want justice and freedom,” said Majid Hussani, 33, an Iraqi exile who recently returned from Syria, before adding: “Until now, they haven’t paid us anything and we’re not very happy about that. They told us they’d pay us.”

Funded under the Iraq Liberation Act passed by Congress in 1998, the fighters are overseen by 200 U.S. special forces and other troops who drive them around, feed and cloth them, train them and confer with them on which patrols to take.

As trucks entered the camp today, a rumor spread that new AK-47 automatic weapons and RPGs had arrived from the U.S. Some of the commanders weren’t sure that was such a good idea, however.

“We’re all familiar with Kalishnakovs,” said Abdul Hamid Salman, recently of Phoenix, Ariz. “Every Iraqi knows how to use them. They’re simple, reliable and all over Iraq. Anything else could make people confused.”

The Free Iraqi troops have mounted patrols into neighboring villages since their arrival from northern Iraq aboard U.S. C-17 aircraft a week ago. As they left the camp Saturday, they waved their rifles in the air and chanted “My Home Iraq!”

American soldiers are training them to set up and man checkpoints, although the front gate of their own base is rather porous as children, religious figures, donkeys and the curious wander in and out.

Just outside the camp -- which was badly bombed by allied forces during the Gulf War and neglected since 1991 by Iraq because it’s in the no-fly zone -- taxis, job-seekers, supplicants and those attracted by the whiff of power gather to chat and meet Chalabi. Inside the barbed-wire fence, old vehicles from bygone battles sit without their doors, wheels, wires or pride after years of neglect and harsh weather.

The fighters are nothing if not excited and self-confident. Several of the recruits -- ranging in age from 18 to their mid-50s -- said they didn’t need training given past experience.

“There was training, but I couldn’t spare the time from my business,” said Salman, 51, a taxi driver in Phoenix. “Plus, I was in the Iraqi army from 1970 to 1972.”

Lines of authority are similarly a work in progress.

“Everyone has the same rank,” said Abdul Salam Kubisi, who joined three months ago. “It’s not like the army. It’s more like brothers, which is much better.”

A U.S. special forces soldier watches the Iraqis line up from an all-terrain vehicle. “The problem is, they really don’t have platoon commanders,” he said. “There are a few officers, but they’re only giving orders over very big groups.”

Many of the uniforms worn by the Iraqi forces were shipped from Hungary, where some of the Iraqi exiles underwent training exercises shortly before the war, and include winter coats, wool gloves and forest-green pants that stand out in the desert.

“My boss gave me these,” said Mohamed Tilb, 29, gesturing to his gloves in the 90-degree heat. “Maybe sometime later I’ll need them.”

The men come filled with the hope that they’re part of the new Iraq and post-Hussein era, having left day jobs as taxi drivers, security guards, shipmates, small shop owners and kaseb -- a catch-all phrase meaning “wheeler-dealers.”

The ragtag group arrived too late to fight much of the war, having been dropped into Nasiriyah from Kurdistan after the U.S. juggernaut had blown through.

“We tried to get involved earlier, but the U.S. ignored us,” said Col. Ahmed Izzet, 38, a former Iraqi soldier. “Then when they find they need us, they let us come. That’s always American policy.”

But they hope to win the peace with their linguistic and cultural ties to local villages. On a patrol to the nearby town of Shatra, children ran out to greet the newly minted Iraqi troops, who carried them on their shoulders and lifted them up onto the Humvees, to the consternation of the security-minded special forces.

There, they met with village tribal leaders, told farmers in this well-armed country to keep their weapons hidden, and instructed locals on how to proceed through checkpoints, the site of several civilian injuries and deaths when locals didn’t stop and Americans opened fire fearing for their lives.

“If we’d been involved in the war from the beginning, we could have avoided more casualties,” Izzet said. “We could talk to people, even Fedayeen, and say don’t be stupid by playing a losing card.”

Each of the soldiers has a story. Roughly half are Iraqis returning home, others never left, while still others arrived recently from Iran, the U.S., Jordan, Syria, Britain, Norway, Canada and Jordan, among other places.

“I came because I heard about it on the radio,” said Haider Mohamed Zaidi, 35, an Iraqi military deserter. “I came by taxi with 14 other people.”

Tilb left Iraq in 1998, having escaped from prison after running into trouble with the Baath Party, then spent the next several years in Syria, Egypt, Nigeria and Cyprus, stowed away on an oil freighter, lived in South Africa for two and a half years, then was jailed in Lebanon for visa violation before answering the home call.

Abu Zaman, 38, a Shiite who arrived here from St. Louis, where he owned a small shop, was forced to flee Iraq because of his involvement in the Shiia uprising of 1991. He had been married all of three hours when Saddam Hussein’s troops roared into the Basra area to crush the rebellion. Afraid he’d be arrested and possibly executed, he left his new bride and escaped through northern Iraq.

Weeks turned into months and eventually years until, in 1994, he got a letter from his sister that the Baath Party had forced his wife to remarry.

“I had a wife for three hours,” he said. “The government divorced her for me and she married someone else.”

Inevitably, a decade of living outside Iraq has altered many people’s lives and outlooks. While most of the soldiers say they are keen to rebuild their lives in Iraq, others have grown too comfortable living in the U.S. or Britain to reverse course and help build the nation up from scratch and dust.

“I don’t want to have my daughter grow up here,” Salman said. “Iraqis have many ideas, but they can’t express themselves. There’s no democracy in Iraq.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.