Howard H. Baker Jr. dies at 88; respected Washington insider

Howard H. Baker Jr., the Republican senator from Tennessee who framed the question that cut to the heart of the official inquiry into the Watergate scandal, died Thursday, four days after a stroke. He was 88.

His death at his home in Huntsville, Tenn., was announced by a spokeswoman at his Memphis law firm, Baker Donelson, where he had been senior counsel.

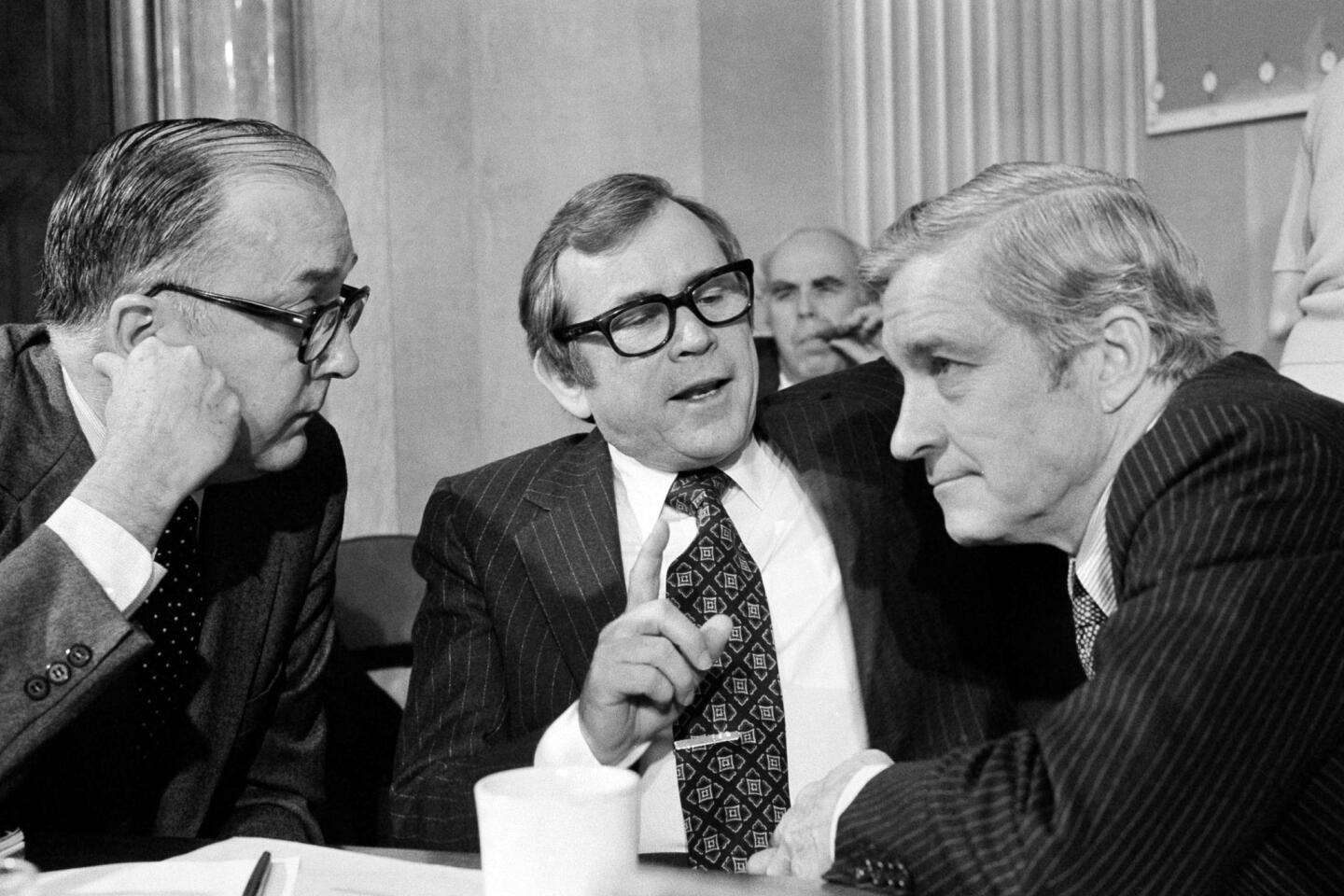

A moderate Republican with bipartisan skill, Baker played many leading roles in his long government career, including White House chief of staff for President Reagan and later U.S. ambassador to Japan. But he was most famous for the one question he asked of witnesses during the 1973 Watergate hearings: “What did the president know, and when did he know it?”

The answers doomed the presidency of Richard M. Nixon and sealed Baker’s reputation as that rare find: a thoughtful politician who, as one reporter suggested, “had nothing at heart but the interests of our country.”

Baker initially believed in Nixon’s innocence, but changed his mind as evidence accumulated of White House involvement in the June 17, 1972, break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington.

The Senate Select Committee to Investigate Campaign Practices — popularly known as the Ervin committee, after its chairman, Sen. Sam Ervin (D-N.C.) — was hardly a coveted assignment for politicians seeking to get ahead. Baker had admired Nixon but was placed on the panel by Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott (R-Pa.) as punishment for having challenged Scott for the leadership post.

The Watergate hearings, televised live, wound up catapulting Baker to national attention, laying the groundwork for his presidential bid in 1980. But his role also drew the distrust of right-wing Republicans, who would never forgive him for contributing to the pressure that forced Nixon’s resignation and later lobbied against his efforts to win the vice presidential spot on the Republican ticket in 1976 and 1980.

The scion of a politically powerful family in Huntsville, a hamlet about 130 miles east of Nashville, Howard Henry Baker Jr. was born Nov. 15, 1925. His grandfather was a judge, his grandmother the first female sheriff in Tennessee. His father was a U.S. representative who served Tennessee’s 2nd District from 1951 until his death in 1964, when Baker’s stepmother, Irene Bailey Baker, served out his last term.

As a child, Baker excelled at debate and photography, two interests that would follow him into adulthood. He studied electrical engineering at the University of the South and at Tulane University. As a lieutenant in the Navy, he served briefly on a PT boat in the South Pacific before World War II ended.

After the war, he returned to college, this time at the University of Tennessee. He switched to law (subsequently telling interviewers that the line for law classes was shorter than the one for engineering) and, in a precursor to his role as a conciliator in Washington, won election as student president by pledging to negotiate disputes between fraternity members and non-frat students. He graduated from the University of Tennessee Law College in 1949.

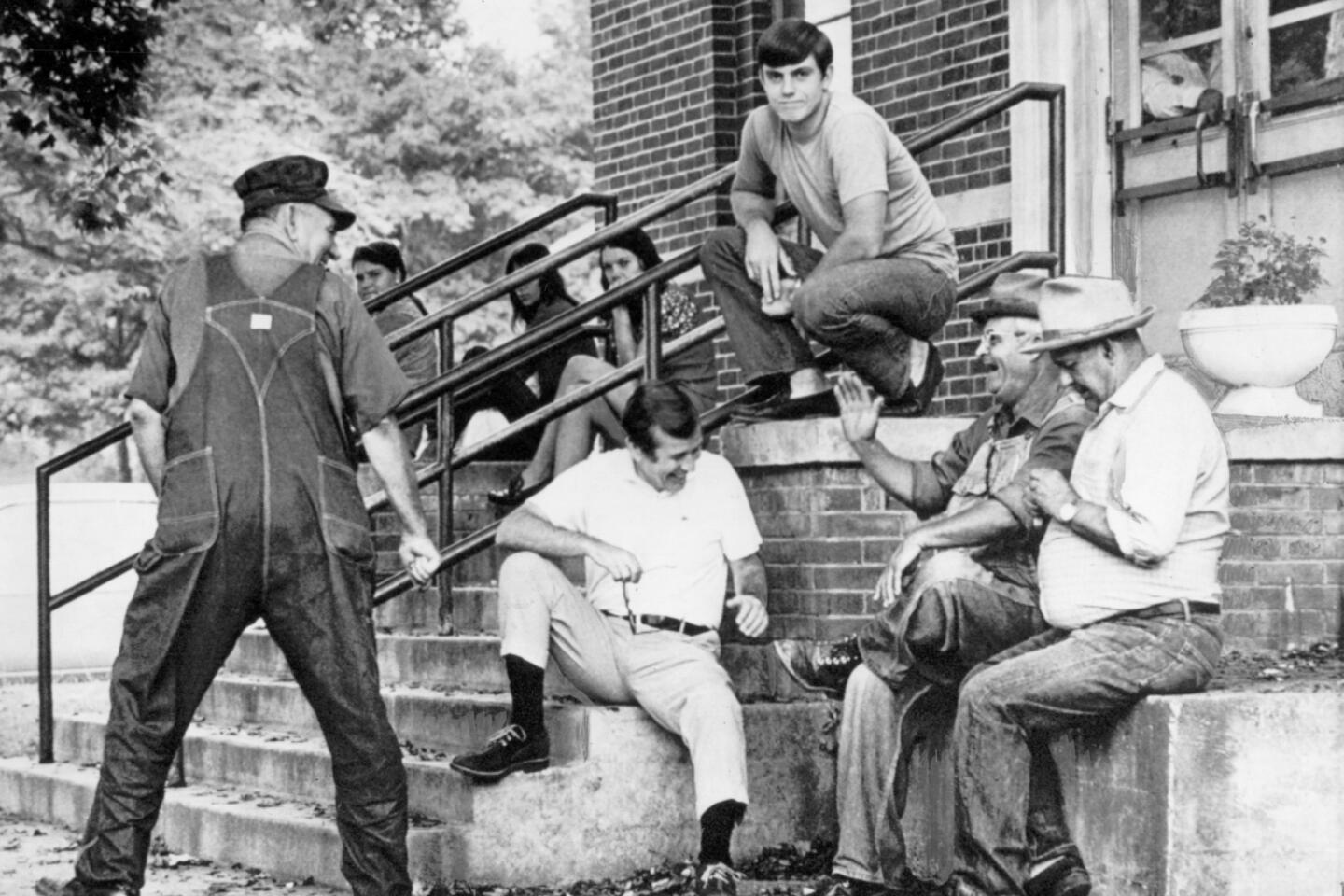

His first run for the Senate was in 1964, to fill the unexpired term of Democratic Sen. Estes Kefauver, who died in office. Baker ran a conservative campaign, promising to limit foreign aid and federal interference in local education and civil rights, and lost to a more liberal candidate. Two years later, he ran again, this time taking more moderate positions — supporting, among other policies, fair-housing laws. He won with nearly 56%, cutting into the traditional Democratic vote and winning an unprecedented 35% of the black vote, and became the first Republican popularly elected to the Senate from Tennessee.

Baker was described as a liberal on environmental issues (he helped draft anti-strip-mining legislation), a moderate on civil rights (he backed landmark voting rights legislation but opposed busing to achieve racial balance in schools, calling it “a grievous piece of mischief”) and a hawk on foreign policy (he voted against SALT II, an arms-reduction treaty with the Soviets but he supported the Panama Canal treaty that ceded control of the waterway to Panama).

For the most part, he was a compromiser and pragmatist who voted for the Equal Rights Amendment, which gave states the option to ratify a constitutional amendment conferring equal rights on women, but against extension of the ratification deadline. James A. Baker III, Reagan’s first chief of staff and later Treasury secretary who was himself a deft manipulator of political strings, once called him “the quintessential mediator, negotiator and moderator.”

In 1976, according to news accounts, the Tennessee senator had hoped to get the vice presidential spot on Gerald R. Ford’s ticket, but that went instead to Sen. Robert Dole of Kansas. Baker sought the top spot himself in 1980, finishing third behind Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush in the New Hampshire primary. Efforts to secure the vice presidential spot on the ticket were again foiled by the party’s right wing.

So Baker remained in the Senate, where his instinct for compromise was rewarded. He was elected minority leader in 1977 and majority leader after the Reagan victory in 1980 swept the GOP into control of the Senate. But acrimony soon overcame his efforts at conciliation, and Baker opted not to seek reelection in 1984. Rep. Al Gore, a Democrat from another famous Tennessee political family, won the seat.

Baker prepared for a third run for the presidency in 1988, but let the White House know he was open to other high-ranking positions. He turned down an offer to succeed the ailing William Casey as director of the Central Intelligence Agency, according to news accounts at the time.

Then the Reagan White House suffered its most significant foreign policy crisis, an arms-for-hostages scandal in which weapons were sold to Iran in an effort to free American hostages held by militants in Lebanon — with the profits diverted to support rebels in Nicaragua, known as the contras. As the Iran-contra crisis consumed the White House, chief of staff Donald Regan resigned. Reagan asked Baker to become his chief of staff, and he helped Reagan begin the process of restoring trust inside and outside the White House.

“We were both extremely grateful that he agreed to take over the role of White House chief of staff during a very challenging time in 1987,” former First Lady Nancy Reagan, who called Baker “one of Ronnie’s most valued advisors,” said in a statement Thursday.

But soon Baker was being blamed for a range of problems, as historian David Eisenhower wrote, “from inconsistent policy statements to legislative defeats to staff amateurism.” He left in July 1988 and returned to law practice in Tennessee, where his wife and his stepmother were both ailing.

Not only was Baker from a prominent political family, but both of his wives had impeccable Republican pedigrees.

In 1951, he married Joy Dirksen, daughter of Sen. Everett McKinley Dirksen of Illinois. The couple, who had met at the wedding of a mutual friend, had two children, Darek and Cynthia, known as Cissy.

Joy Baker was hospitalized for problems with alcohol in the 1970s and stopped drinking in 1975. She attributed her problems to the strains of a political life. She died in 1993 after a 10-year battle with cancer.

Three years later, in a match that surprised and delighted their friends, Baker married former Sen. Nancy Landon Kassebaum of Kansas.

The two had known each other as friends and colleagues since 1978, when she was first elected to the Senate and he was Senate Republican leader. Kassebaum asked Baker if he would administer the oath of office in Topeka, so that her ailing father, Alf Landon, the former Kansas governor who ran for president in 1936, could attend.

Baker capped his career in 2001 when he was named ambassador to Japan. He served until 2005.

Besides his wife and children, Baker is survived by four grandchildren.

Neuman is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.