Nevada Supreme Court hears arguments for using untested paralytic drug in death penalty case

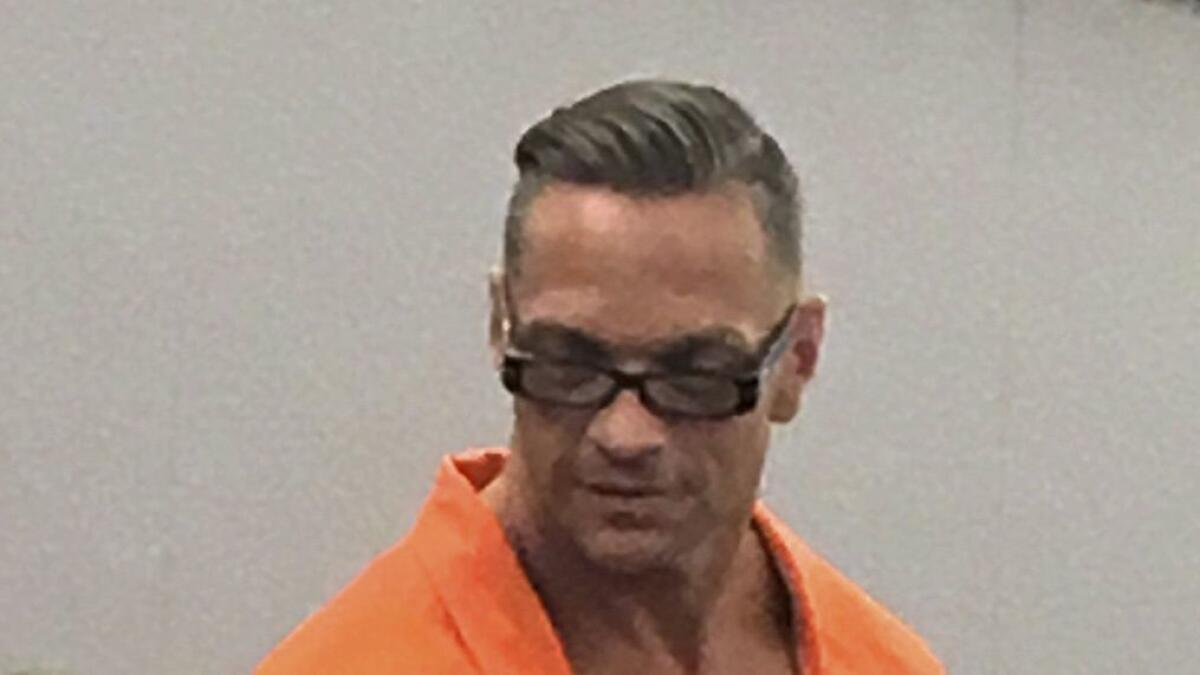

Scott Dozier wants to die. The state of Nevada wants to kill him.

Which left Dozier’s attorney arguing before the Nevada Supreme Court on Tuesday not about whether he would be executed but how.

For the record:

10:40 a.m. May 9, 2018An earlier version of this article incorrectly said some of the state’s supply of fentanyl had expired. It was some of the state’s supply of cisatracurium that had expired.

David Anthony, a federal public defender, told the seven justices that the state’s proposed addition of the paralytic drug cisatracurium to a lethal execution regimen is unnecessary and would simply mask any mistakes made while administering two other drugs, fentanyl and diazepam.

“Their protocol has no upside and unlimited downside,” Anthony said.

But Assistant Solicitor Gen. Jordan Smith, arguing for the Nevada Department of Corrections, said the case was bigger than Dozier and that his lawyers were using it to prevent the use of the death penalty for other convicts. He called the Dozier case “a de-facto ban on the death penalty” in Nevada.

“The arguments being made here are an attack on the death penalty itself,” Smith said.

Dozier, 47, was convicted in 2007 of murdering and dismembering 22-year-old Jeremiah Miller five years earlier at a Las Vegas motel. He also was convicted in Arizona 13 years ago for the 2001 murder of 26-year-old Jasen Green.

He has steadfastly expressed his desire to die and has refused to allow his attorneys to file for a stay of execution. More than a year ago, he waived his appeals.

He did, however, allow his legal team to press ahead in arguing against the use of the paralytic drug on the grounds that it is inhumane and could cause unneeded pain and suffering to future inmates facing execution.

Anthony’s arguments leaned heavily on testimony made by Dr. David Waisel, a Boston-based anesthesiologist, who testified last year in Clark County District Court that the state’s lack of practice in administering the new combination of drugs makes the protocol ripe for error.

“It is a dramatically unfamiliar situation and location for the individuals performing the injections,” Waisel wrote in a brief. “Even for experienced individuals this increases risk; it is increased even more for the inexperienced, especially without high-quality practice.”

The state is in a bind, however.

There is no protocol for executions using only the two drugs, which means a new procedure would have to be developed and prison staff would need to be trained. And the state’s supply of diazepam expired May 1 — a point hammered by Justice James Hardesty.

“Doesn’t that make this matter moot?” he asked the lawyers.

Smith said the state would try to obtain more diazepam. He also told the court that Dozier’s legal team has dragged out the proceedings — knowing the state’s supply of the drug was about to expire.

Some of its cisatracurium supply has expired, but Smith said enough was still on hand to carry out the execution.

Other states have struggled to replenish their supplies of execution drugs.

Fordham University law professor Deborah Denno said in an interview that because many of the drugs used for executions are manufactured in European countries that oppose the death penalty, there has been a reluctance to sell to states for that purpose. Even U.S. pharmaceutical companies don’t want their drugs to be associated with executions, she said.

Last year, McKesson Medical-Surgical sued Arkansas after it discovered the state was using one of its drugs in an attempt to execute 10 men in eight days. The company said the state had mislead the drug company by saying the purchased drugs were being used for other medical reasons.

Lethal injection has been used in executions since 1977, and a three-drug protocol of sodium thiopental, pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride was the standard until 2009.

But as states began having difficulty acquiring drugs, they were forced to adapt. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, eight states now have carried out executions using a single drug — and anesthetic — and six others plan to do so if necessary.

Nevada has executed a total of 12 people since 1976 — most recently in 2006. Dozier’s lawyers argued that Nevada doesn’t frequently apply the death penalty and that infrequency makes the state more at risk to make a mistake.

Anthony said the use of a new, untried three-drug protocol compounded that problem and argued that is why District Court Judge Jennifer Togliatti ruled in November against the state’s use of the three drugs. The state, which had planned to execute Dozier that month, appealed her ruling.

Smith said the risk of a mistake is not a reason to not use the procedure.

“There will always be the chance of human error, no matter how many safeguards are in place,” Smith said. “That there might be a bungle is not an argument against it.”

During about 90 minutes of oral arguments, the justices peppered the lawyers with questions about the procedures of the execution and why Dozier was arguing against it when he clearly wanted to die.

Justice Michael Cherry asked Anthony for “a bottom-line” answer.

“Will he withdraw his request to die?” Cherry asked.

“No,” Anthony said.

“He will die whether we approve a three-drug protocol or a two-drug protocol?”

“Yes,” the attorney said. “Regardless of how the court rules, as I far as I know, Mr. Dozier’s wishes are to proceed with an execution.”

It’s unclear when the Nevada Supreme Court will issue a ruling.

Twitter: @davemontero

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.