The difference between Richard Nixon and John Travolta, plus other things to know about Trump, Comey and special prosecutors

With his abrupt firing of former FBI Director

Critics assert that Trump’s move was an attempt to stymie the FBI’s probe and insist the only way to ensure a full, impartial investigation is to hand the matter to a special prosecutor with no ties, or obligations, to Trump or his administration.

The president and his surrogates have adamantly insisted the Trump campaign had nothing whatever to do with Russian meddling in the presidential race and efforts to find a connection are nothing more than partisan witch-hunting.

What makes a prosecutor special? Are they faster than a speeding bullet?

Stop it.

So what is it?

A special prosecutor, or independent counsel, enjoys broad investigative power with wider-ranging authority than a typical federal prosecutor.

The law calls for appointment of a special counsel if it is determined a criminal probe is warranted, the investigation “would present a conflict of interest” for the

The “special” simply means they’ve been selected to pursue a specific matter; a kind of one-off.

Who decides whether appointment of an outside counsel is merited?

The short answer is the U.S. attorney general.

And the longer answer?

That goes back to the 1970s-era Watergate scandal, which involved a break-in at the Democratic Party headquarters by operatives connected to President Nixon’s reelection campaign. (The headquarters was housed in the Watergate office complex alongside Washington’s Potomac River, establishing “–gate” as a scandal-denoting suffix ever since.)

After the myriad abuses of the Nixon administration, which led to his resignation,

So it’s up to the attorney general or Congress?

Stick with me here.

OK.

Not anymore. Members of both parties were frustrated with the actions of past special prosecutors, including, most notably, Kenneth Starr, whose investigation of President Clinton morphed from a look into a failed Arkansas real estate deal to a tawdry probe of his extramarital affair with White House intern Monica Lewinksy.

Lawmakers were concerned that the cost and free-ranging nature of previous investigations had gotten out of hand, so they allowed the independent counsel law to lapse. In its place is a system in which only the attorney general can appoint a special prosecutor, with their investigative scope limited to criminal activities.

In this instance, however, Atty. Gen.

Rosenstein wrote the memo that urged Trump to fire Comey.

So Congress has no say?

Not when it comes to an independent counsel. Lawmakers could vote to create a high-profile House-

In the meantime, separate investigations are underway by the House and Senate intelligence committees. Graham, who leads a subcommittee with oversight of the FBI, is heading up a third probe.

You use “special prosecutor,” “independent counsel” and “special counsel” interchangeably.

That’s because they’re all the same. Some frown on the term “special prosecutor” because it has a kind of guilty-until-proven-innocent connotation.

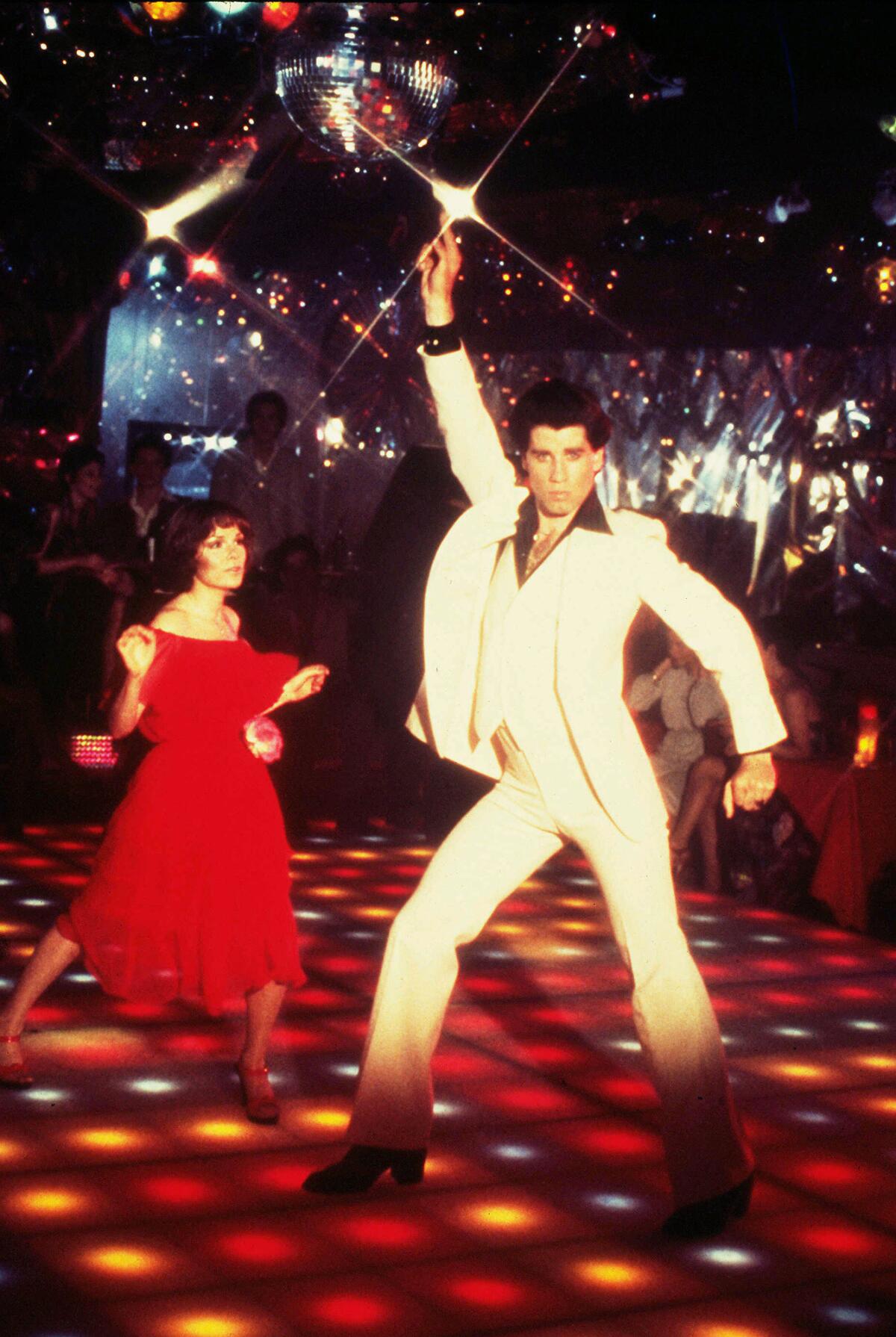

I keep hearing about the “Saturday Night Massacre.” Is that the disco movie starring John Travolta ?

No, that was “Saturday Night Fever.”

Oh.

The “Saturday Night Massacre” occurred Oct. 20, 1973. As the coils of the Watergate scandal tightened around him, President Nixon sought to fire Archibald Cox, the special prosecutor appointed to investigate the June 1972 Watergate break-in and subsequent White House cover-up.

Nixon’s attorney general, Elliot Richardson, and Richardson’s chief deputy, William D. Ruckelshaus, both resigned rather than carry out Nixon’s order.

“Saturday Night Fever” had the much better soundtrack.

Agreed.

But firing the special prosecutor. That was certainly Nixonian!

Hence, the abundant use of that adjective of late. But it also could be described as “Grant-like.”

Come again?

President Ulysses S. Grant, who presided over one of the most corrupt administrations in history, appointed the country’s first special prosecutor, Gen. John B. Henderson, in 1875. His charge was to take on the St. Louis Whiskey Ring and a kickback scheme involving taxes on distilleries in Missouri. When the probe crept too close to the White House, Grant fired Henderson and then acted to undercut the effectiveness of his replacement.

So much history! Is there precedent for Sessions’ recusal?

There is. Atty. Gen.

Do tell!

It was Ashcroft’s No. 2, Deputy Atty. Gen. James Comey.

Small world!

Indeed.

ALSO

A sudden fall for an FBI director once seen as above the fray and untouchable

Trump urged Comey to go after Clinton — and then fired him for it

Annotated letter: the Trump administration’s case for firing FBI Director James Comey

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.