Uncovering the untold history of civil rights at a martyred zealot’s farm

At this small town at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, there is a history that is well-known and a history that has been hidden.

The familiar history is the story of militant abolitionist John Brown, who on the night of Oct. 16, 1859, came with a party of 22 raiders to seize the United States arsenal. His objective was to provoke a slave revolt that would spread throughout the South. Instead, Brown and his compatriots were trapped inside an engine house just inside the gate of the arsenal grounds. U.S. Marines under the command of Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, the future Confederate commander, killed 10 of the raiders and took Brown prisoner. Brown was tried for treason against the state of Virginia — a dubious offense — and was hanged.

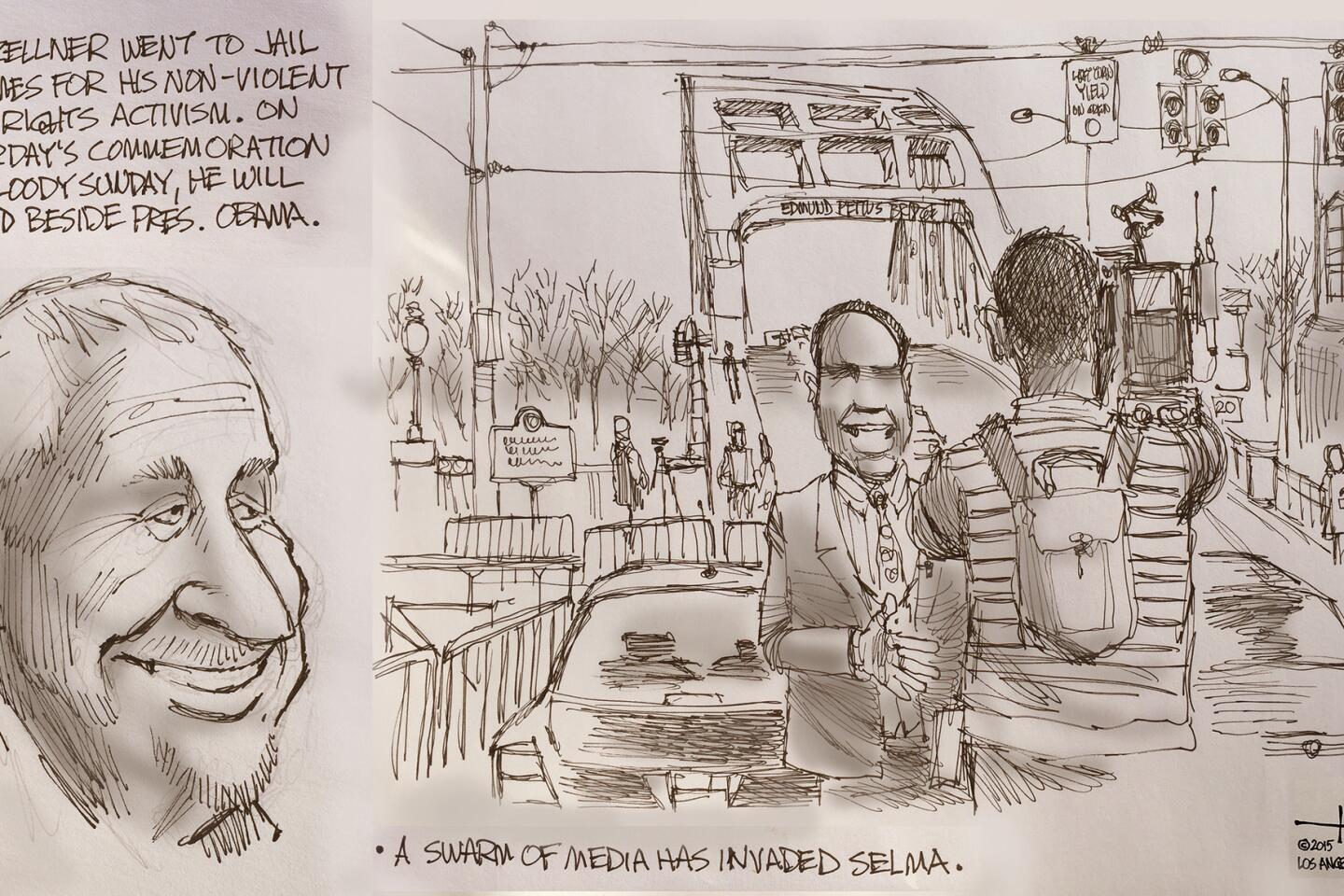

I heard this tale retold by a National Park Service guide, Jim Silvia, while sitting in the restored engine house with my fellow Project Pilgrimage sojourners. All visitors to Harper’s Ferry will hear this story, but Silvia added more to his narrative by taking us up the hill to the site of Storer College. Opened at the end of the Civil War in 1865, the publicly supported school was open to anyone. Because it served black students, though, no whites ever enrolled. Ironically, when desegregation became the law of the land, federal and state funding was withdrawn on the pretext that African Americans could now attend any college they chose, and Storer was shut down in 1955.

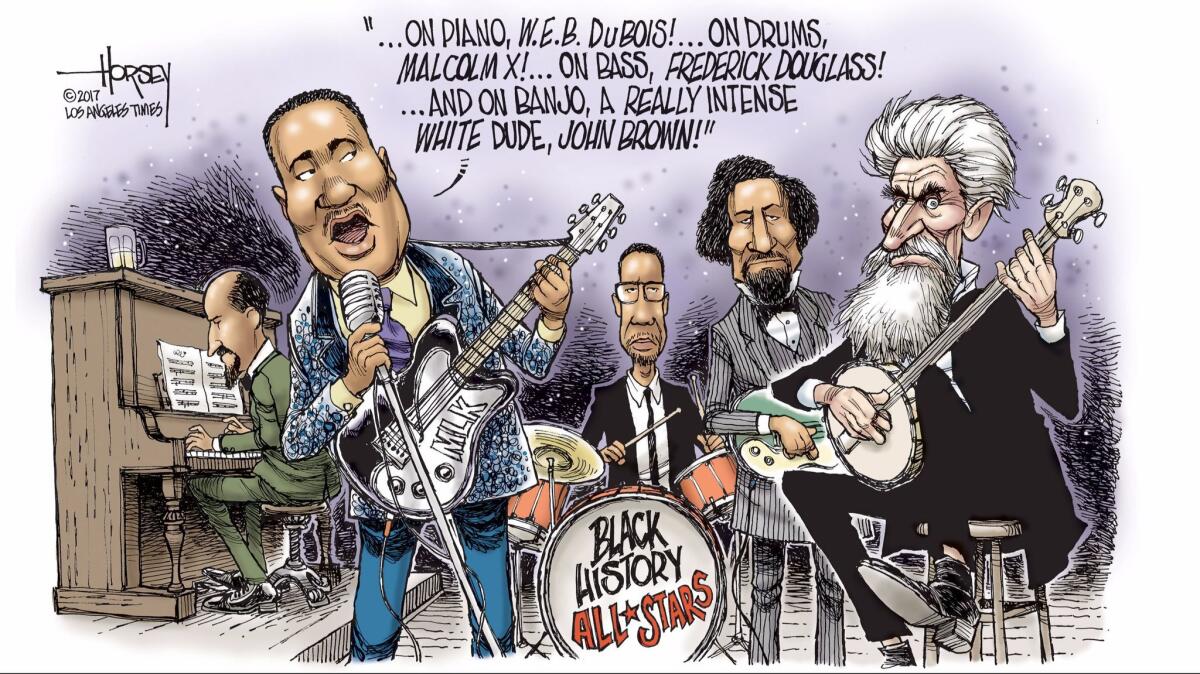

The college is, arguably, the birthplace of the civil rights movement because it was there that the precursor to the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, the Niagara Movement led by W.E.B. DuBois, held a national conference in 1906. DuBois returned to the Storer campus in 1932 with the intention of installing a plaque to memorialize John Brown, who by then had achieved saintly status among black Americans. White Southerners emphatically did not share that view, and DuBois was dissuaded from erecting the memorial. One like it was not installed on the grounds until 2004.

Brown remains a controversial figure. When the National Park Service held an event marking the 150th anniversary of the abolitionist’s raid, Silvia said, a troop of Ku Klux Klan members paraded around a book tent on the Storer grounds to express their displeasure.

Brown was a true radical. He makes today’s anti-fascist protesters and window-smashing anarchists look like children scuffling on a playground. Prior to the raid, he holed up with several of his men in a remote farmhouse four miles outside Harper’s Ferry, where they plotted and trained for revolution. Lee called Brown “a fanatic or a madman.” DuBois hailed him as a hero who “aimed at human slavery a blow that woke a guilty nation.” When we visited the restored farmhouse, we were greeted by a rather convincing wax figure of Brown seated at a table with guns ready. I contemplated the possibility that both Lee and DuBois were right.

Just a few paces up the hill from Brown’s hideout, we discovered another bit of black history that few white folks know about. In 1950, after buying the farm property to preserve as a shrine to John Brown, the African American fraternal organization known as the Black Elks built a nearby auditorium. It is now a vacated wreck, but between 1950 and 1965, it became a remote but successful stop on the Chitlin Circuit, the string of dance halls and bars stretching from Boston to Austin where black musicians performed for black audiences shut out of other venues by segregation.

African Americans would drive in from as far away as Baltimore and Washington to dance and groove with nearly every top black performer of the era — Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Little Richard, B.B. King, Etta James, Ray Charles, Chubby Checker, Fats Domino and many more. Ed Maliskas, a musician who wrote a book about the remarkable place, titled “John Brown to James Brown: The Little Farm Where Liberty Budded, Blossomed and Boogied,” guided us through the empty hall. An older black man, Al Baylor, a local who had come along with Maliskas, reminisced about the dance hall in its heyday, when he was a teenager. He remembered the necessity of buying a new suit, shirt, tie and shoes so that he would look as sharp as everyone else, and how the new clothes would be wet and limp after hours of dancing. Smiling wide, Baylor recalled standing in front of the stage mesmerized by the shimmy and shake of a young Tina Turner.

Maliskas made a good argument that music has had as much influence on changing white American attitudes toward race as any other force. The music streamed out of the Mississippi Delta and Chicago and Harlem. It caught fire in clubs and saloons in the black communities. It got put on vinyl at Motown in Detroit and at Stax Records in Memphis, Tenn. It spread into the receptive minds and tapping toes of white teenagers everywhere. It formed common bonds of culture, smashed stereotypes and subverted prejudices.

The music played and sung at John Brown’s farm created a revolution, one as big as fanatical old John Brown ever imagined in his wild, wild dreams.

This is part four of a five-part series.

Tomorrow: Finding inspiration at Gettysburg.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.