Great Read: Often criticized, Serra gets a reappraisal from historians

When archaeologist Ruben Mendoza was a boy, his father was prone to fiery outbursts in the family’s mobile home on the tough west side of Fresno. One of the biggest targets of his anger, Mendoza remembers, was the Catholic Church and its California missions.

“Over and over, he claimed Catholic missions were cancers that Spain brought to the New World,” Mendoza said.

Mendoza, who is of Yaqui Indian and Mexican American heritage, was shaped by his father’s hatred.

“I became obsessed with ‘pure’ ancient Indian cultures,” he recalled.

When his fourth-grade class built models of the historic missions, he asked his teacher if he could do something else -- and got special permission to build a dinosaur instead.

Mendoza, one of the founding faculty members at Cal State Monterey Bay, grew up believing that the controversial founder of the missions, Franciscan friar Junipero Serra, now on a track for sainthood, was an imperious theologian who imposed a slave system that destroyed the Indians’ way of life.

Later, his archaeological research revealed that the real story is more complicated than the caricature.

“Dig a little deeper,” the 58-year-old likes to say, “and you’ll find evidence of a new diverse society flourishing, one that makes California and its Latino culture unique.”

But not until he uncovered the chapel where Serra celebrated the first high Masses in Monterey did Mendoza have an awakening that finally changed how he felt about the priest.

::

Mendoza is among a growing number of historians who have spurred a reappraisal of Serra, whom Pope Francis is expected to elevate to sainthood in September.

The Spaniard was 56 and asthmatic when he arrived in California, then hobbled thousands of miles on an ulcerated leg to launch a mission-building campaign that stretched from San Diego to San Francisco.

Advocates say that he defended native people against soldiers and settlers, and laid the foundations of California’s vibrant agricultural and commercial economy. But critics point to the friars’ often brutal treatment of Native Californians.

In February, a dozen people led by Olin Tezcatlipoca, director of the Mexica Movement, an indigenous-rights group, gathered outside a Sunday Mass at the downtown Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels to protest the proposed canonization of the friar whom they say was responsible for “genocide” of native peoples.

“Serra set up forced labor camps, death camps,” Tezcatlipoca said in an interview at the time.

Like many Mexican Americans, Douglas Monroy, a professor of history at Colorado College in Colorado Springs and an associate of Mendoza, has conflicted emotions of sadness, anger and reverence for Serra and the missions.

“When I think of all the death and dying,” he said, “I, like so many of the Indians who lived in [the missions], must flee because I become so angry. In God’s name, they have ruined the Indian peoples of California.”

In their new biography, “Junipero Serra: California, Indians, and the Transformation of a Missionary,” historians Rose Marie Beebe and Robert M. Senkewicz portray Serra as a man whose commitment embroiled him in frequent conflicts with California’s early governors, soldiers, settlers and other missionaries.

“Serra was not a monster,” said Senkewicz, a professor of history at Santa Clara University.

Mendoza, a practicing Roman Catholic, says that critics of Serra and other missionaries overlook what he achieved.

“Serra endured great hardships to evangelize Native Californians,” he said. “In the process, he orchestrated the development of a chain of missions that helped give birth to modern California.”

Flogging and shackling were common punishments for Indians in Serra’s missions, Mendoza said. But documentation also shows that Serra felt Indians stood a better chance of surviving depredation by Spanish soldiers and colonists if they were brought into the fold of the missions.

“The missions were not slave plantations like those of George Washington or Thomas Jefferson,” Mendoza said. “They were communes in which friars and Indians worked side by side and consumed the products of their labor.”

::

That kind of talk would have infuriated Mendoza’s father. “My father was raised Catholic but he rejected the church when I was a boy,” Mendoza recalled.

“He instilled a zealous appreciation for only one part of my ethnic identity,” Mendoza said. “It stayed with me through graduate school.”

Even after he earned a doctorate in anthropology at the University of Arizona in 1992, his attitude persisted. “If there was an old mission located next door to an ancient archaeological site I was excavating, I just ignored it as inconsequential.”

A new perception began to take hold a year later, when he was invited by the Mexican government to excavate a 16th century convent in Puebla.

“It was a transformative experience,” he recalled. “We uncovered evidence of an incredibly diverse mass of humanity” — Spanish colonial foundations, pre-Columbian floors and figurines, and Aztec ceramics.

“I realized that I would never fully understand the arc of history in such places if I exclude their Spanish cultural dynamics,” he said.

Since then, “archaeology has been a high-wire act for me,” he said. “Skeptics believe I’ve been compromised by some personal desire to honor my ancestors — all of them. When I don’t go along with the idea that the missions were concentration camps and that the Spanish brutalized every Indian they encountered, I’m seen as an adversary.”

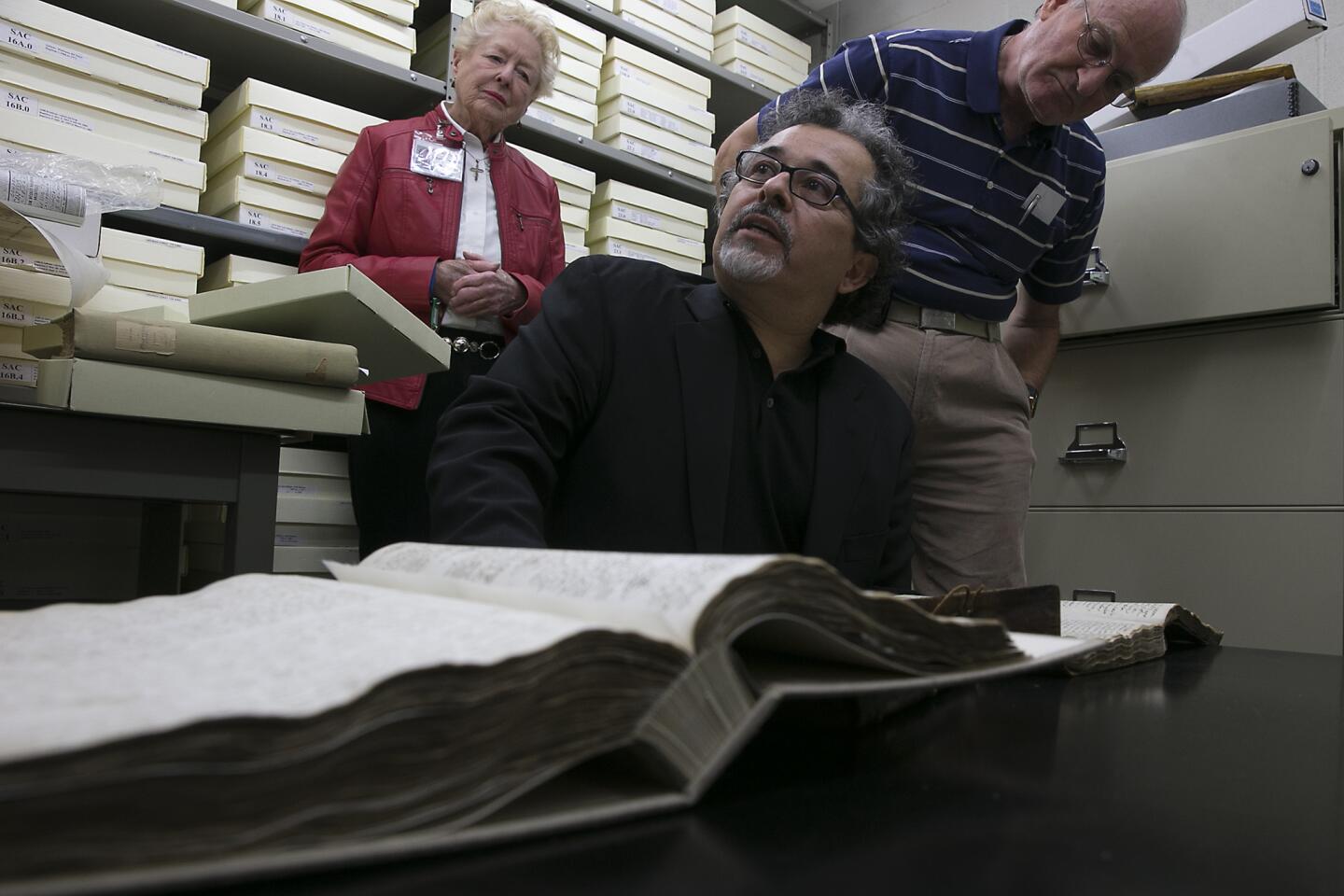

In 2006, Mendoza was recruited by the Diocese of Monterey to assess the structural integrity of San Carlos Cathedral, one of the nine missions Serra founded before his death in 1784. The next year, Mendoza noticed an unnaturally straight row of stones in a trench where new utility lines were being laid near the cathedral.

Mendoza’s observation led to further exploration and to discovery of buried chapels used by Serra in the early 1770s, a find that is shedding new light on Spanish explorers in the New World and some of the momentous “firsts” in California history.

Within those chapels about 245 years ago, friars administered the first sacrament of “exploration” to Capt. San Juan Bautista de Anza, who went on to chart San Francisco Bay. There, they conducted the first Christian baptism of a Native Californian and blessed the first cemetery in Alta California.

There too, Mendoza came to terms with his conflicted ethnic identity.

Mendoza felt a surprising kinship with Serra as he and a team of archaeology students uncovered the charred postholes and decomposed granite foundations of the chapels where, according to historical accounts, Serra had celebrated the first high Masses in Monterey.

As the excavated site was being reburied in 2008 during a ceremony, Mendoza was suddenly overwhelmed by a sense of admiration of Serra’s frontier evangelism, a view at odds with what he had been taught by historians, teachers and his father: Indians were brutally coerced into acculturation by overzealous Franciscans.

Mendoza discreetly positioned himself over what would have been the altar of one of the chapels, then dropped to his knees and made the sign of the cross.

“After years of rejecting the California mission era, I felt a powerful personal connection with it,” Mendoza said. “I’m Iberian, indigenous and Mexican. It took years to reconcile those differences. But I was born here.”

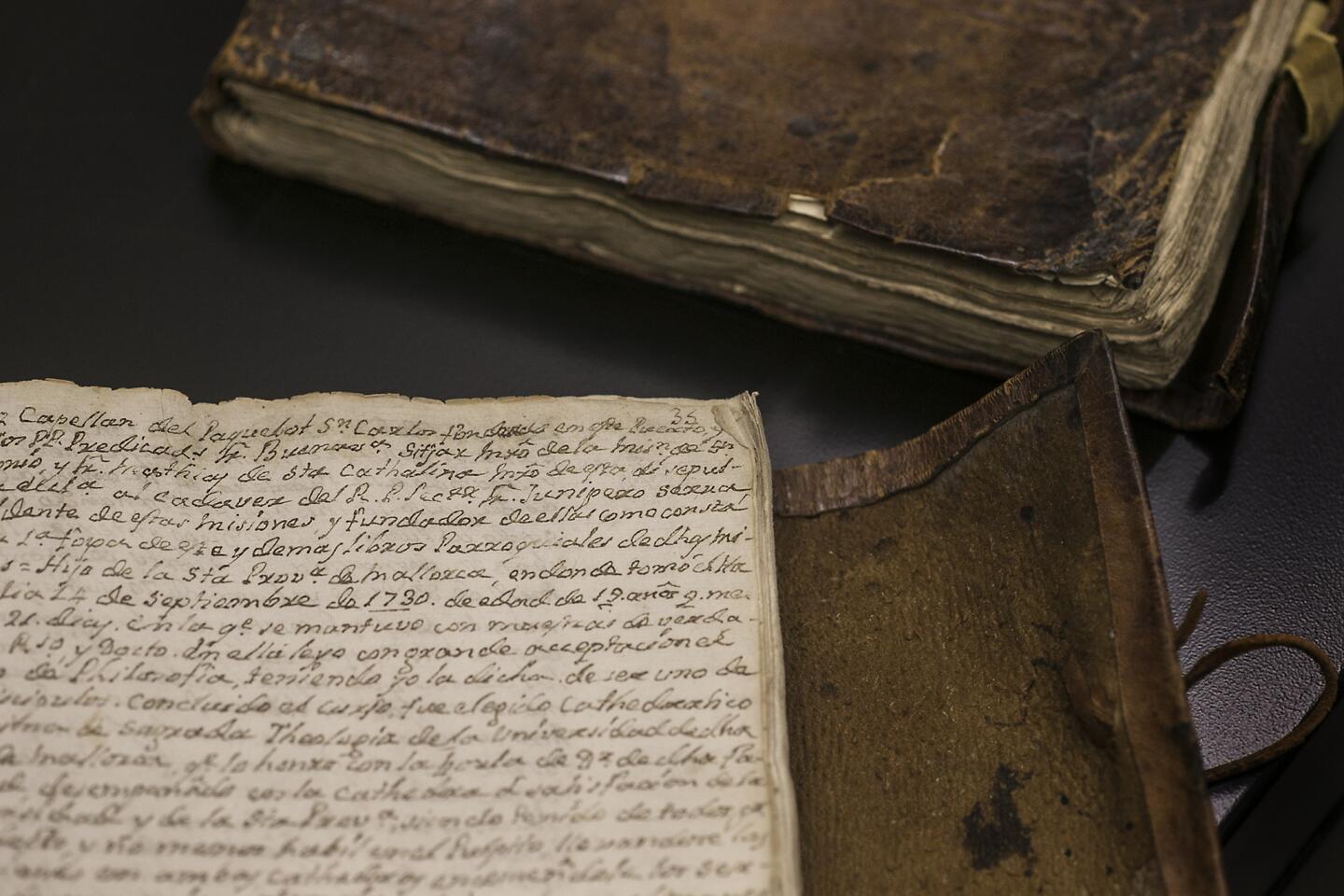

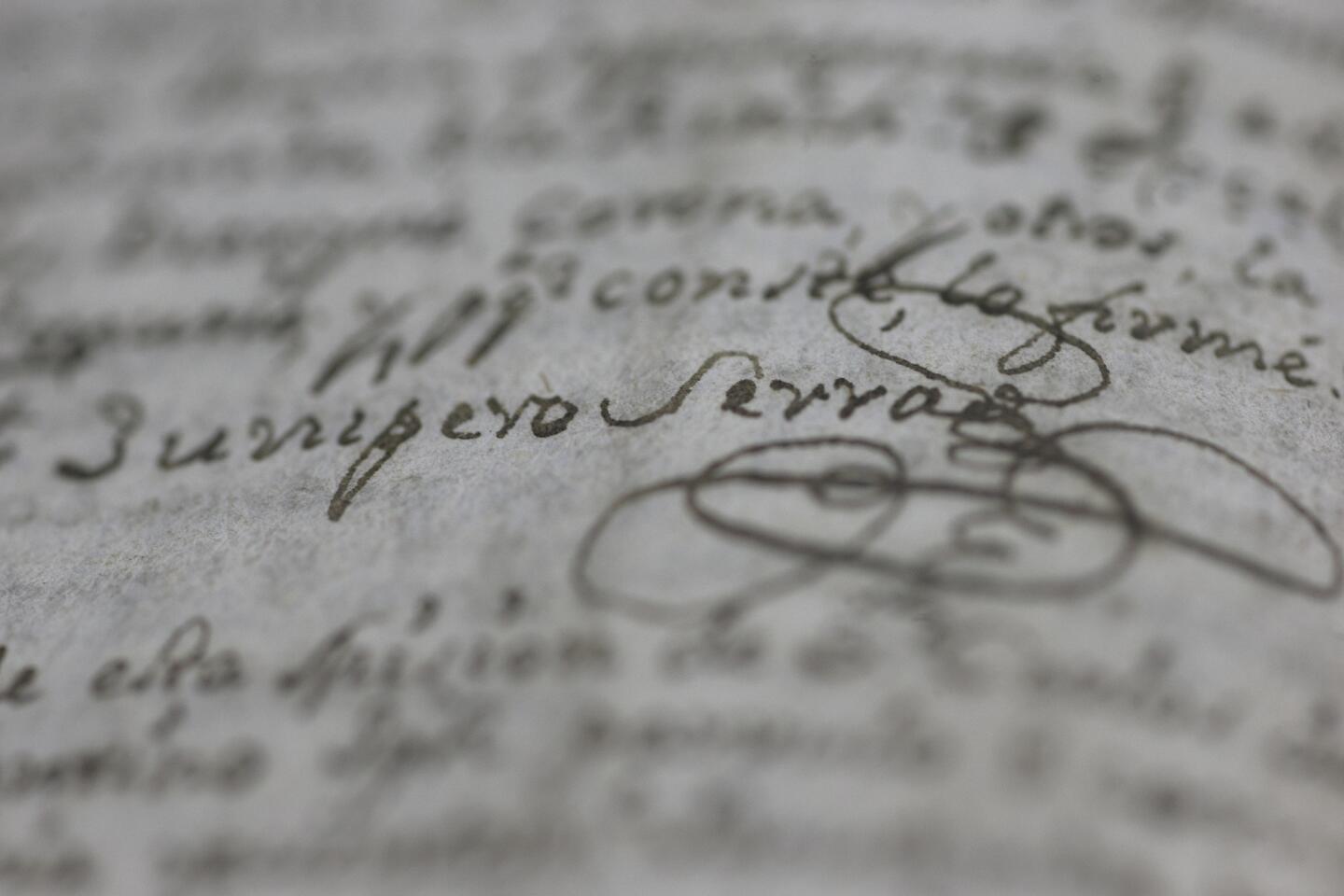

On a recent day, inside a temperature-controlled cathedral vault, Mendoza held up one of Serra’s tattered leather-bound marriage and baptism ledgers.

On the first page, Serra recorded the first Christian baptism of a Native Californian, 5-year-old Bernardino de Jesus, on Dec. 26, 1770. In florid handwriting, he said he reminded Royal Presidio of Monterey Commander Don Pedro Fages of his obligation as baptismal godfather to ensure that the boy would be raised in the Christian tradition.

“Serra was far from perfect,” said Mendoza, whose pickup truck bears the bumper sticker “I Dig Missions.” “Yet we are beneficiaries of this man who believed that poverty, chastity and obedience would open the gates of the kingdom of heaven to Native Californians.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.