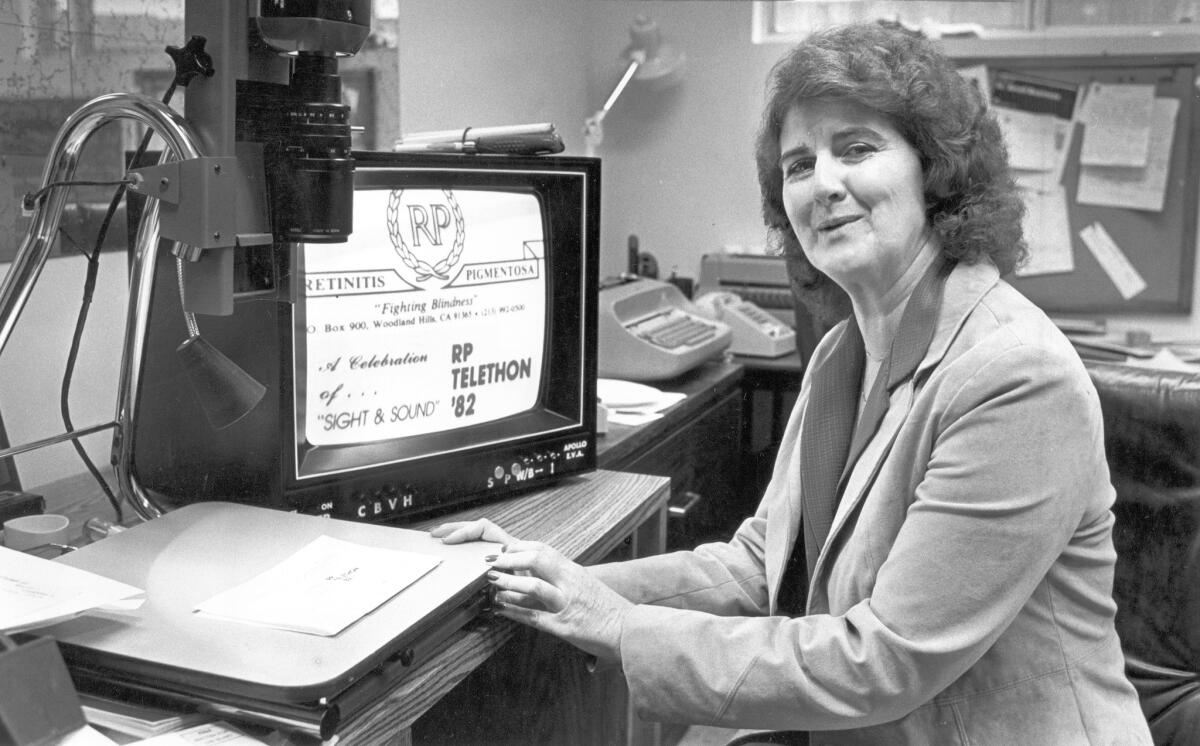

Helen Harris dies at 78; enlisted celebrities to fight eye disease

As a wedding party nervously went through its paces, the event planner managed to ask one of the worst questions in the history of wedding rehearsals: “What shall we do about the blind woman? Will she be able to light the candle?”

The “blind woman” was Helen Harris, an activist who was raising millions of dollars for research into eye diseases and developing ways to make movies more accommodating to visually impaired viewers. With her white cane, she moved confidently among the Hollywood elite and she wasn’t about to be patronized at her son’s wedding rehearsal.

“At the top of my lungs, louder than I am happy to admit, I shouted, `If you’re talking to me, you’d better come down here and talk to my face!’ ” she recalled. And yes, she told the stunned planner, she would light the candle, and “it will be done the same way it is for every other normal human being on the planet.”

Harris, a tenacious organizer who held glitzy, black-tie benefits and persuaded numerous stars and former President George H.W. Bush to narrate “descriptive audio” for blind people watching films, died on Christmas Eve at her Woodland Hills home. She was 78.

She had been battling aggressive metastatic breast cancer for eight years, her son Bob Harris said.

At the same time, she was still active in RP International, a nonprofit she founded in 1974 after learning that two of her three young sons had retinitis pigmentosa, an eye disease that can lead to total blindness. RP had taken most of Harris’ sight and when her son Jim came home bruised after a Halloween night fall in 1972, she suspected the worst. After all, she too had spent her childhood stumbling in the dark.

“The doctors tell me there’s no cure and no treatment,” she told her sister Doris after her sons’ diagnosis, “and that we might as well just go home and decide that we’re going to be blind.”

Harris herself was diagnosed in her early 20s. As her vision grew worse, she took up oil painting, a small act of defiance against the encroaching darkness.

“I looked at my kids’ faces very closely, all the hair lines, the tips of their ears, the width of their shoulders,” she told The Times in 1999. “When they got out of the pool, I’d look at their footprints as they dried in the concrete.”

After starting RP International, she packed away her paints and relentlessly nagged celebrities for their support.

“Nobody was safe from Mom’s reach,” her son Bob said in an interview this week. “There was nowhere you could hide, nowhere you could go.”

After Bob Hope brushed her off again and again, Helen Harris left dozens of balloons for him in a hospital where he was having surgery. He agreed to host an RP telethon, Harris’ son said.

When Harris was about to hold her first major fundraising dinner, she received the standard polite regrets from the staff of then-L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley. She finally showed up at a City Hall meet-and-greet, grabbed Bradley’s arm and said: “I am going blind and so are my children. I need you to move a mountain for me. This is a dinner invitation.”

He attended.

When Harris started the audio service called TheatreVision in 1994, she enlisted a host of big names as volunteer readers. As limited-vision viewers plugged in their earpieces at special screenings of “Forrest Gump,” they heard Dodgers announcer Vin Scully give a play-by-play between bits of dialogue:

“Still pursued by the pickup truck, Forrest runs at top speed through a chain-link gate on to the school athletic field. In the stands is legendary Alabama football coach Bear Bryant, wearing his trademark plaid hat. Bryant and the high school coach watch as Forrest runs past the team … and keeps running.”

While TheatreVision did not originate descriptive audio, it became a major player in the field, applying the technique to hundreds of movies and TV shows. Working with writers, Harris contributed to the descriptions herself.

“I sit with someone and say, `What kind of car was that? Her dress must be beautiful--what does it look like?’ I teach them about the blank spaces that a blind person hears,” she told The Times.

Harris snagged James Cameron, Angie Dickinson, Katharine Hepburn and many other stars as narrators, but her greatest coup may have been from outside Hollywood.

Every Christmas since 2002, a familiar voice has described bucolic Bedford Falls, nasty Mr. Potter and the goings-on in the 1946 Frank Capra classic “It’s A Wonderful Life.”

“Hello, I’m George Bush,” the voice says. “I’m proud and happy to be the first president to describe a film for the visually challenged.”

Harris wangled a quick meeting with Bush shortly after he became president in 1990.

Born to Irish immigrants in Philadelphia on Sept. 17, 1936, Helen Josephine O’Malley first noticed trouble seeing when she was 8. However, she wrote, tests at the time failed to pick it up because they did not measure her declining peripheral vision.

“At the time, family teachers, friends and even our doctors thought my resultant stumbling and fumbling were simply signs of ‘clumsiness,’ ” she wrote in her 2011 book, “How to Survive Losing Vision.”

“Of course I believed them,” she wrote. “I changed from a vivacious little girl into a teenage wallflower.”

Her true condition became known accidentally. She accompanied her cousin, who was scheduled for brain surgery, to a medical appointment and nonchalantly told the doctor that she too kept falling down stairs and getting into accidents.

The doctor checked her eyes and re-examined her cousin. Both women had RP. The surgery was canceled.

In 1958, Helen married Robert Harris, a boy she had known in high school who became a petrochemical engineer for Atlantic Richfield. After a job transfer, they moved to Woodland Hills in 1972.

Since founding RP International, Harris sponsored the annual Vision Awards dinner in Los Angeles for more than 40 years, raising funds and honoring a host of luminaries.

Harris’ husband died in 1999.

In addition to her son Bob, her survivors include sons Jim and Richard; and three grandchildren.

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.