South Carolina lawmakers to consider taking down Confederate flag

South Carolina lawmakers took their first steps Tuesday to remove the Confederate battle flag from the Statehouse grounds amid a growing controversy over whether such symbols are racist or just a celebration of heritage.

As hundreds of protesters marched and prayed outside, lawmakers in the state House and Senate approved holding a debate on the banner, whose presence has taken on new urgency since last week’s attack by a white gunman on the landmark black Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Nine African Americans were slain, including the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, who was also a state senator. His body will lie in state at the capitol on Wednesday.

Civil rights activists had wanted the Confederate battle flag removed before Pinckney’s body was in the building. But lawmakers couldn’t act that fast, despite calls to take down the flag from the governor, both of the state’s U.S. senators and most top politicians, white and black, on both sides of the aisle.

Legislative leaders have yet to decide when to call lawmakers back to debate and vote on removing the flag. State Sen. Tom Davis said that debate was not likely until late July.

“We’re captive to the rules here, and the rules require a bill to be passed,” said Davis, a Republican. “Procedurally,” he said of the voice vote that moved the process along, “that was the Senate acting at lightning speed.”

The House held a moment of silence for Pinckney, then voted 103 to 10 to debate the flag.

The South Carolina law that allows the Confederate battle flag to fly on Statehouse grounds came under intense scrutiny after the attack on the church June 17. Dylann Roof, 21, who had boasted of racist beliefs and had posed in photographs with Confederate flags and symbols, is being held on nine murder charges.

“Never again may someone use that red rag to take people’s lives,” said the Rev. Nelson B. Rivers III, a pastor and official with the National Action Network, to thunderous applause at the rally outside the Statehouse. “Make this day — this day — the day the flag comes down.”

The Confederate flag has flown on the grounds of the Statehouse for more than five decades. The state first raised the flag atop the capitol in 1961, the centennial of the beginning of the Civil War. The Legislature made the flag’s position official the next year.

Many scholars note that the reemergence of the flag in Southern states coincided with — and represented defiance against — the civil rights movement. Georgia incorporated the flag into its state flag in 1956 — two years after the U.S. Supreme Court declared, in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, that separate public schools for black and white students were unconstitutional.

“The Confederate flag symbolizes more than the Civil War and the slavery era,” James Forman Jr., a professor at Yale Law School, wrote in a journal article about the flag’s history at Southern state capitols. “The flag has been adopted knowingly and consciously by government officials seeking to assert their commitment to black subordination.”

In 2000, on the anniversary of the birth of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., more than 45,000 people marched through South Carolina’s capital, Columbia, calling for the flag’s removal. In a compromise, the flag was moved from the dome to a Confederate war memorial in front of the Statehouse, on one of Columbia’s busiest downtown streets.

As the flag was hoisted into its new position, supporters chanted, “Off the dome and in your face!” Protesters held signs reading “Shame.”

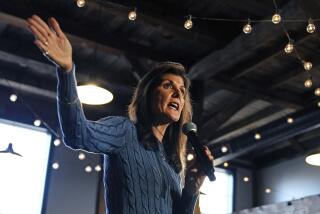

Republican Gov. Nikki Haley reversed her position on the flag Monday, calling for its removal from the Statehouse grounds.

She noted that for many South Carolinians, the flag represents noble traditions of heritage and duty. But for many others, it is a “deeply offensive symbol of a brutally oppressive past.”

“The hate-filled murderer who massacred our brothers and sisters in Charleston has a sick and twisted view of the flag. In no way does he reflect the people in our state who respect, and in many ways, revere it,” Haley said.

Both of the state’s Republican U.S. senators, Tim Scott and Lindsey Graham, joined in calling for its removal. Graham, one of the dozen announced candidates for the GOP presidential nomination, had publicly defended flying the flag as recently as last week, before national political pressure began to build from those who decried Confederate symbols as racist.

Hillary Rodham Clinton, the leading contender for the Democratic presidential nomination, called the Confederate flag “a symbol of our nation’s racist past that has no place in our present or our future.” She praised South Carolina’s leaders for taking steps to remove it from the Statehouse grounds.

“It shouldn’t fly there. It shouldn’t fly anywhere,” she said Tuesday.

Clinton made the remarks at a black church near Ferguson, Mo., where a young black man, Michael Brown, was shot dead by a white police officer in August. Brown’s death launched a national debate over race and inequities in the justice system.

Haley’s announcement led to other actions in the South.

Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, moved on Tuesday to banish the Confederate flag from one of that state’s license plates.

In Mississippi, state House Speaker Philip Gunn, a Republican, called for the Confederate emblem to be removed from that state’s flag, to which it was first added in 1894.

In Tennessee, Democrats and Republicans called for the removal of a bust of Confederate Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, an early Ku Klux Klan leader, from an alcove outside the state Senate’s chambers.

And several companies, including Sears, Amazon and EBay, moved to follow Wal-Mart, which had announced Monday that it would remove any items from its store shelves and website that featured the Confederate flag.

Even NASCAR, which attracts Confederate symbols on cars and spectators alike, entered the fray. The sport’s governing body issued a statement endorsing Haley’s decision.

Jarvie reported from Columbia and Muskal from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Kathleen Hennessey in Florissant, Mo., contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.