After 150 years, Ku Klux Klan sees opportunities in U.S. political trends

Born in the ashes of the smoldering South after the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan died and was reborn before losing the fight against civil rights in the 1960s. Membership dwindled, a unified group fractured and one-time members went to prison for a string of murderous attacks against blacks. Many assumed the group was dead, a white-robed ghost of hate and violence.

Yet today, the KKK is still alive and dreams of restoring itself to what it once was: an invisible white supremacist empire spreading its tentacles throughout society. As it marks 150 years of existence, the Klan is trying to reshape itself for a new era.

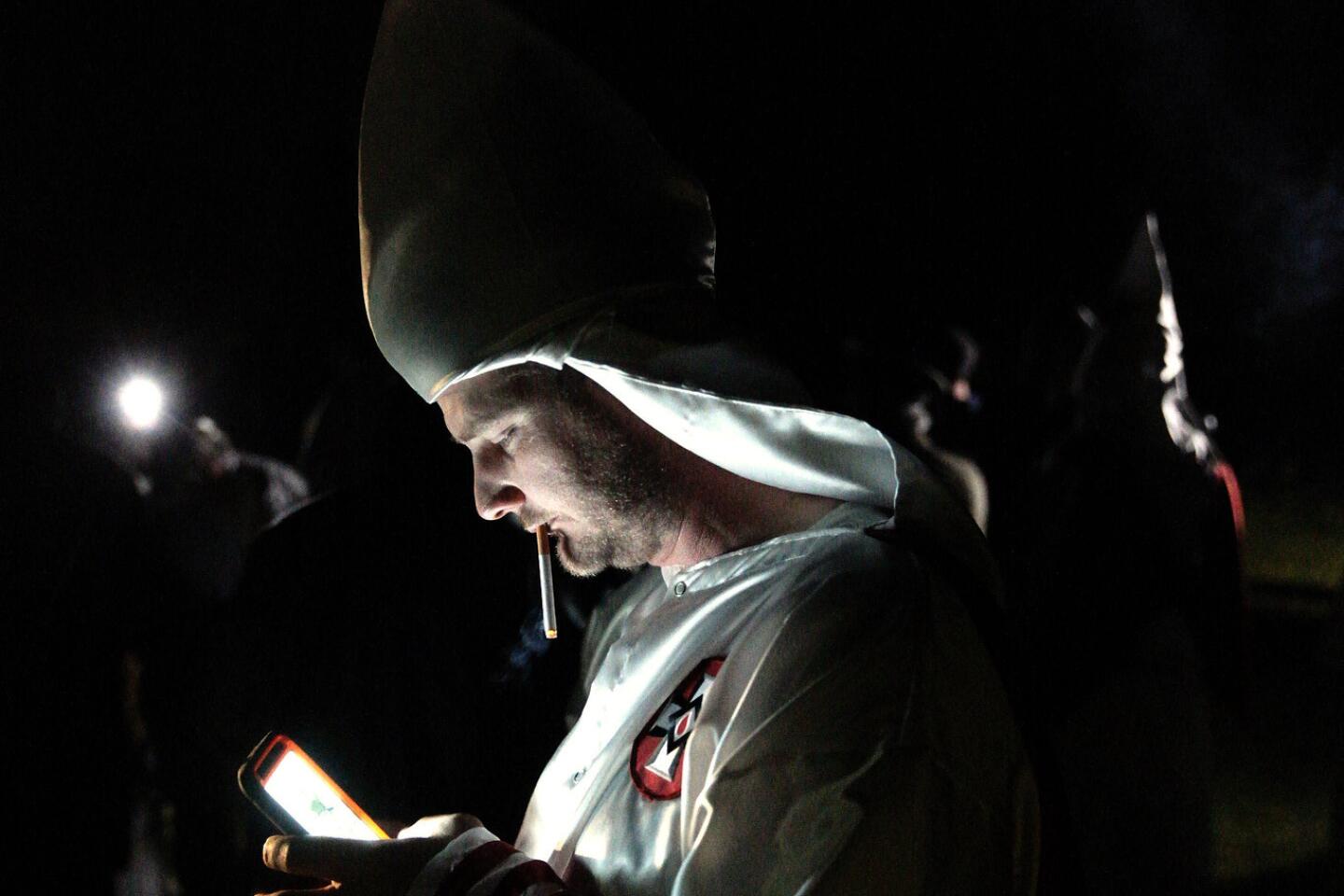

Klan members still gather by the dozens under starry Southern skies to set fire to crosses in the dead of night, and KKK leaflets have shown up in suburban neighborhoods from the Deep South to the Northeast in recent months. Perhaps most unwelcome to opponents, some independent Klan organizations say they are merging with larger groups to build strength.

“We will work on a unified Klan and/or alliance this summer,” said Brent Waller, imperial wizard of the United Dixie White Knights in Mississippi.

In a series of interviews with the Associated Press, Klan leaders said they feel that U.S. politics are going their way, as a nationalist, us-against-them mentality deepens across the nation. Stopping or limiting immigration — a desire of the Klan dating back to the 1920s — is more of a cause than ever. And leaders say membership has gone up at the twilight of President Obama’s second term in office, though few would provide numbers.

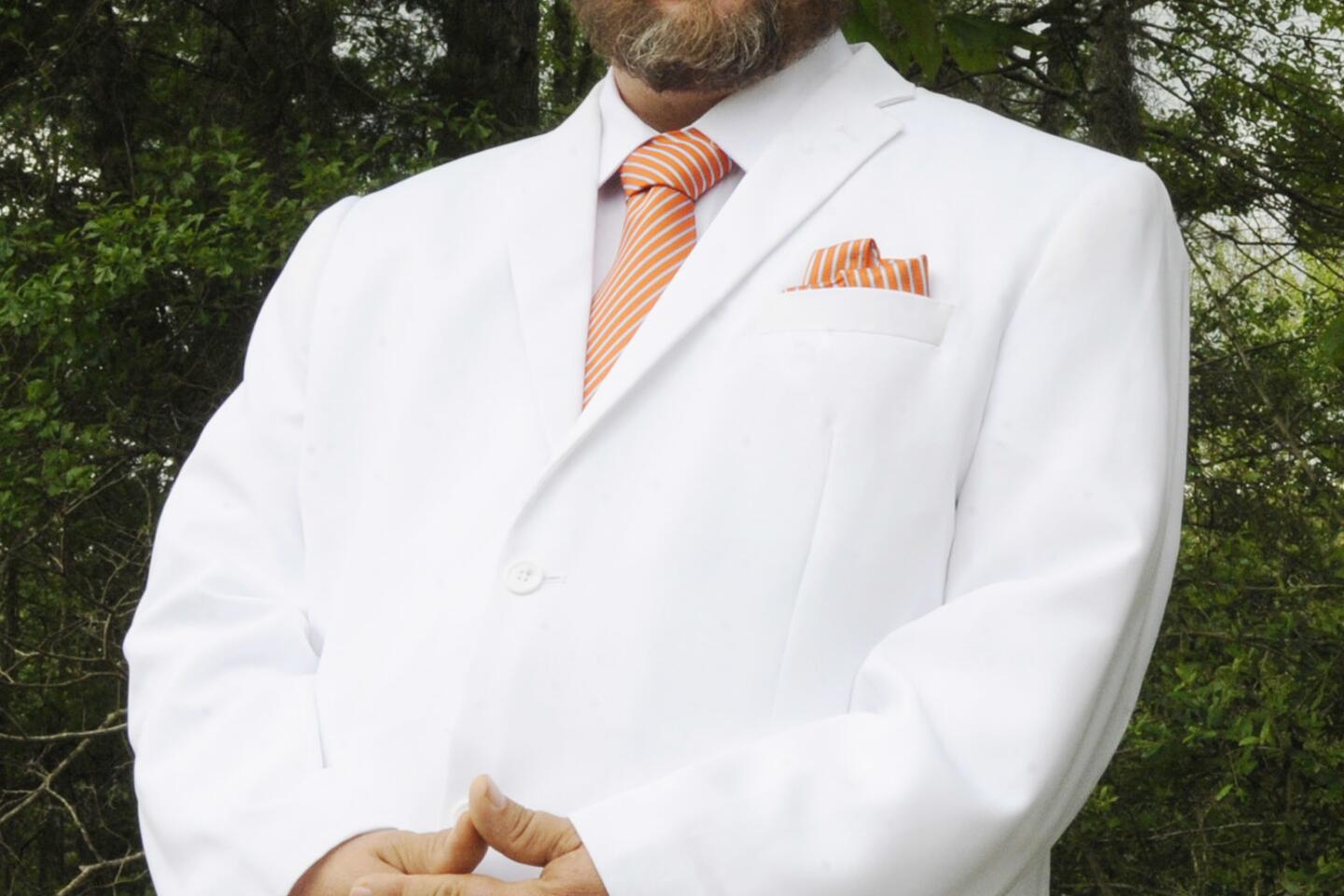

Joining the Klan is as easy as filling out an online form — provided you’re white and Christian. Members can visit an online store to buy one of the Klan’s trademark white cotton robes for $145, though many splurge on the $165 satin version.

While the Klan has terrorized minorities during much of the past century, its leaders now present a public front that is more virulent than violent. Leaders from several Klan groups all said they have rules against violence, aside from self-defense, and even opponents agree the KKK has toned itself down after a string of members went to prison years after the fact for deadly arson attacks, beatings, bombings and shootings.

The idea of unifying the Klan like it was in the ’20s is a persistent dream of the Klan, but it’s not happening.

— Mark Potok, Southern Poverty Law Center

“While today’s Klan has still been involved in atrocities, there is no way it is as violent as the Klan of the ’60s,” said Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center, an advocacy group that tracks activity by groups it considers extremist. “That does not mean it is some benign group that does not engage in political violence,” he added.

Historian David Cunningham, author of “Klansville, U.S.A.: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan,” notes that while the Klan generally doesn’t openly advocate violence, “I do think we have the sort of ‘other’ model of violence, which is creating a culture that supports the commission of violence in the name of these ideas.”

Klan leaders told the AP that most of today’s groups remain small and operate independently, kept apart by disagreements over such issues as whether to associate with neo-Nazis, hold public rallies or wear the KKK’s trademark robes in colors other than white.

So-called “traditional” Klan groups avoid public displays and practice rituals dating back a century; others post Web videos dedicated to preaching against racial diversity and warning of a coming “white genocide.” Women are voting members in some groups, but not in others. Some leaders will not speak openly with the media, but others do, articulating ambitious plans that include quietly building political strength.

Some groups hold annual conventions, just like civic clubs. Members gather in meeting rooms to discuss strategies that include electing Klan members to local political offices and recruiting new blood through the Internet.

It’s impossible to say how many members the Klan counts today because groups don’t reveal that information, but leaders claim adherents in the thousands among scores of local groups called Klaverns. Waller said his group is growing, as did Chris Barker, imperial wizard of the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Eden, N.C.

“Most Klan groups I talk to could hold a meeting in the bathroom in McDonald’s,” Barker said. As for his Klavern, he said, “Right now, I’m close to 3,800 members in my group alone.”

The Anti-Defamation League, the Jewish protection group that monitors Klan activity, describes Barker’s Loyal White Knights as the most active Klan group today but estimates it has no more than 200 members total. The ADL puts total Klan membership nationwide at around 3,000.

The Alabama-based Southern Poverty Law Center says there’s no evidence the Klan is returning to the strength of its heyday. It estimates the Klan has about 190 chapters nationally with no more than 6,000 members total, which would be a mere shadow of its estimated 2 million to 5 million members in the 1920s.

“The idea of unifying the Klan like it was in the ’20s is a persistent dream of the Klan, but it’s not happening,” Potok said.

Formed just months after the end of the Civil War by six former Confederate officers in Pulaski, Tenn., the Klan originally seemed more like a college fraternity, with ceremonial robes and odd titles for its officers. But soon, freed blacks were being terrorized, and the Klan was blamed. Hundreds of people were assaulted or killed within the span of a few years as whites tried to regain control of the defeated Confederacy. Congress effectively outlawed the Klan in 1871, leading to martial law in some places and thousands of arrests, and the group died.

The Klan seemed relegated to history until World War I, when it was resurrected. It grew as waves of immigrants arrived aboard ships from Europe and elsewhere, and it grew further as the NAACP challenged Jim Crow laws in the South in the 1920s. Millions joined, including community leaders such as bankers and lawyers.

That momentum declined, however, and best estimates place Klan membership at about 40,000 by the mid-’60s, the height of the civil rights movement. Klan members were convicted of using murder as a weapon against equality in states including Mississippi and Alabama, where one Klansman remains imprisoned for planting the bomb that killed four black girls in a Birmingham church in 1963.

Cunningham, the historian, said the Klan dwindled to nearly nothing during the 1970s and ’80s, when the Southern Poverty Law Center sued the Alabama-based United Klans of America over the 1981 murder of Michael Donald, a black man whose beaten, slashed body was hanged from a tree. In an odd twist, Donald’s mother wound up with the title to the Klan’s headquarters near Tuscaloosa, Ala., because the group didn’t have the money to pay the $7 million judgment awarded in the lawsuit.

Associated Press writer Ryan Phillips in Stone Mountain, Ga., and AP photographer Mike Stewart in Rome, Ga., contributed to this report.

ALSO

5 KKK members released from jail after brawl in Anaheim

Criticism of Anaheim police response to KKK rally mounts, hunt for assault suspect continues

Bay Area school threatened after teacher clashes with neo-Nazis at state Capitol

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.