Louisiana Senate runoff may be last stand for Mary Landrieu, Democrats

After Mary L. Landrieu had finished, after Louisiana’s beleaguered U.S. senator was done touting her work bringing disaster relief and high-speed Internet service and street lamps and drainage pipes and defense dollars and so much more to her hard-pressed state, there was just one more thing.

“I think we need some prayer,” Landrieu said.

With that she joined more than a dozen ministers — hands clasped, heads bowed — offering their silent entreaties before a largely black audience in the squat brick community center of this small university town.

At this point, divine intervention may be the only thing that can save Landrieu, 59, who faces a runoff Saturday that just about everyone — save, perhaps, the senator herself — fully expects her to lose.

A defeat would not just put a grim punctuation mark on a dismal year for Democrats, who have already surrendered eight seats along with control of the U.S. Senate. Landrieu’s ouster also would mark an epochal moment in the nation’s politics, removing the last Democratic senator from the Deep South, which once served as a foundation of the national party.

A victory by Republican Bill Cassidy, 57, an unsung three-term congressman from Baton Rouge, would serve as well to underscore another important shift in today’s politics, as ideology and party identity grow more important than parochial interests and the acquisition of federal dollars, which Landrieu has emphasized in her desperate last stand — titled, hopefully, her “Louisiana First Victory Tour.”

Simply put, the Democratic label has become toxic across the South, and it may be too much for even Landrieu, a part of Louisiana political royalty, to overcome.

Not that she isn’t trying. In a brief interview after a stop this week at a black church in Shreveport, Landrieu strove to separate herself from the national party and the pounding Democrats took last month, from Maine to Florida to Alaska. Louisiana, she insisted, is different.

“People, I think, will go to the polls and say, ‘You know what? We might have been mad at the Democratic Party nationally and we might be mad at this or that, but we’re not mad at Mary and she’s done a good job,’” said Landrieu. “So that’s what we’re fighting for.”

National Democrats and their allies spent more than $10 million trying to help Landrieu win the Nov. 4 election. When that failed — she finished with 42% support, well shy of the majority needed to avoid a runoff and just a percentage point ahead of Cassidy — the party’s Senate campaign committee effectively gave up, pulling its TV advertising and leaving the incumbent to largely fend for herself.

(Some of Landrieu’s fellow senators have emailed supporters asking that they chip in to save their embattled colleague, and a few party luminaries have visited, including New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker.)

In a sense, Landrieu suffered twin defeats last month: the failure to win outright and a second blow when Democrats lost control of the Senate.

Gone was the incentive for the debt-ridden national committee to invest any further in this increasingly Republican state. Gone, too, was one of the chief arguments Landrieu had made for another term: her clout as head of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, an important perch given Louisiana’s vital oil and gas industry. Win or lose, she will now surrender the chairmanship when the GOP takes control in January.

To a great extent, though, Landrieu is not fighting Cassidy so much as larger, more powerful forces.

The shift in Southern political allegiances began just about 50 years ago, spurred in good part by the civil rights movement of the 1960s. The white exodus from the Democratic Party hastened in the 1980s under Ronald Reagan, who lured traditional Democrats to the GOP with his message of lower taxes, social conservatism and a muscular national defense.

That helped overcome resistance among Southern whites accustomed to voting for Democrats out of habit or ancestral loyalty more than any affinity for the party or its national candidates, who were seen as increasingly beholden to the party’s left-wing constituencies.

“They came to realize their views were best represented by Republicans,” said Brian Brox, who teaches political science at New Orleans’ Tulane University. “The Democratic Party now stands for the liberal party and Republicans for the conservative party, and whites are increasingly voting Republican to match their conservative values.”

Landrieu, who first won election to the Senate in 1996, has survived through a combination of good fortune and nimbleness. She gives a feisty, fist-shaking stump speech and this week was greeted with warm hugs at every stop, in big cities and small towns, which spoke to both her familiarity and attentiveness to local concerns.

Landrieu was born into a political dynasty — her father, Moon, was a former New Orleans mayor, a job her younger brother, Mitch, now holds — and she was repeatedly blessed with a series of less-than-top-flight opponents.

Even so, Landrieu has never broken 52% in any of her three Senate races, including in 2008, when President Obama drew a large and enthusiastic African American turnout.

Moreover, the positions that stood her in good stead at home, including opposition to late-term abortion and skepticism toward environmental regulation, alienated many of the national interest groups that have become an increasingly crucial source of money and manpower for Democratic candidates.

“I don’t represent people all over the country,” she said crisply after rallying black supporters at Shreveport’s Mount Canaan Baptist Church. “I represent the people of Louisiana.”

As for Obama, he is deeply unpopular in the state, save in the African American community, which offered Cassidy a simple, straightforward strategy, pursued with great success by Republicans across the country: tying Landrieu to the president at every turn. Cassidy’s TV ads, running virtually uncontested from dawn to well past dark, remind voters that Landrieu backed the president in 97% of the votes taken by the Senate.

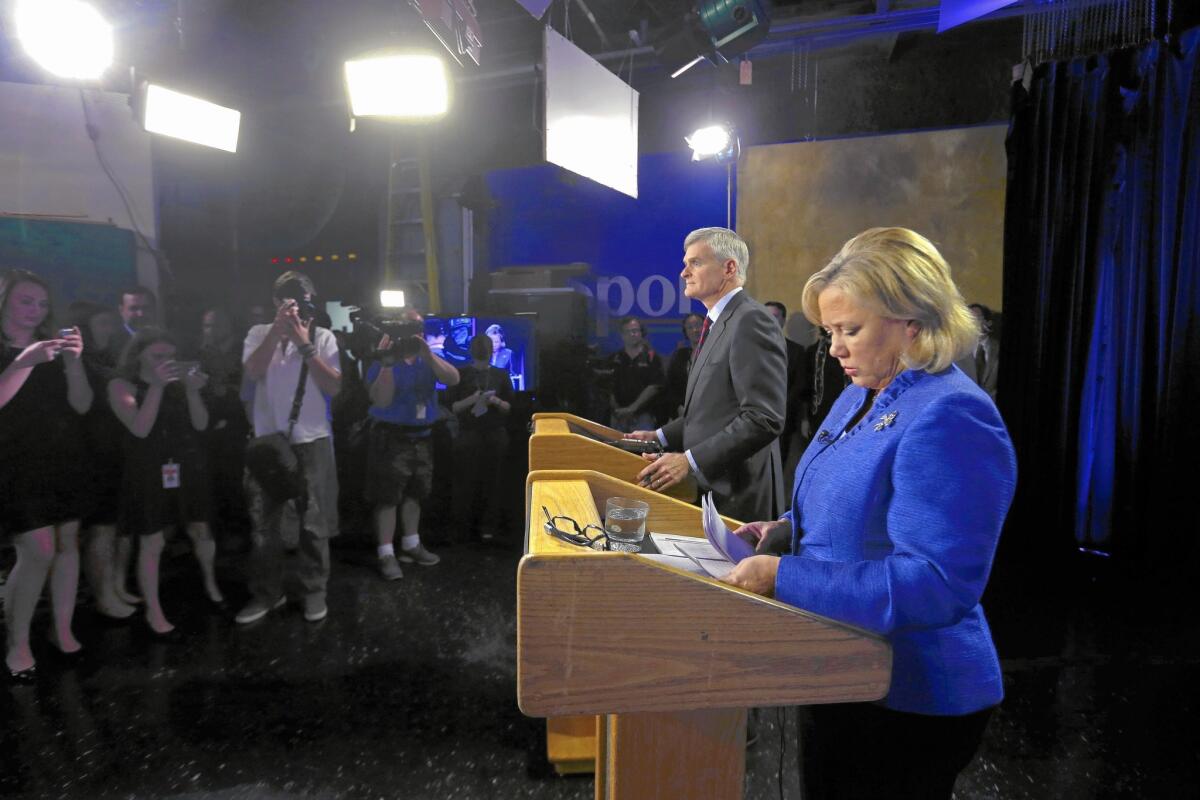

Landrieu has faced a far more difficult task distancing herself from Obama, as she did in the candidates’ lone debate Monday night — “He shut down oil and gas drilling. We are all for it” — at the same time she assailed Cassidy for “disrespecting the president of the United States,” as she has done repeatedly to nods and murmurs of assent from sympathetic black audiences.

Her last-gasp reelection hopes rest on a late-breaking controversy over $20,000 in annual pay that Cassidy, a doctor, has drawn from Louisiana State University’s medical school, on top of his congressional salary. Landrieu cited the absence of time sheets and called Cassidy’s work fraudulent and improper double-dipping at taxpayer expense; her GOP opponent called the allegations “absolutely false.”

In the closing days, Landrieu — orphaned from her national party, voice scratchy from overuse — repeatedly cited her first Senate run, when she came from behind in a runoff and eked out victory by 5,788 votes, or an average of 1 per precinct.

“That’s gonna happen again on Saturday,” she said to applause from a small crowd gathered on the steps of the colonnaded courthouse in rural Minden.

If so, it will be a stunner — and entirely her own doing.

Twitter: @markzbarabak

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.