‘Hamilton’ gets past race by imagining Founding Fathers with black and brown faces

Imagine if Vice President Mike Pence killed President Obama’s first Treasury secretary, Timothy F. Geithner, in a gunfight. Even in the current craziness of American politics, that would be unthinkable, right? But something similar and equally startling actually happened when the United States was still a fledgling nation, suggesting that politics in this country has seldom been a dispassionate business run by flawless human beings.

In 1804, Vice President Aaron Burr fought a duel with the country’s first Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton, the man most responsible for shaping the U.S. Constitution and establishing the American economic system. Hamilton was mortally wounded in the confrontation and, for long decades afterward, he was relegated to a place of relative historical obscurity compared with his contemporaries George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson.

Now, Hamilton’s complex story has been reimagined in the hugely popular, Pulitzer-and-Tony-award-winning hip-hop musical “Hamilton,” created by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Evidence of the 37-year-old Miranda’s mastery of musical theater is the way he managed to make compelling entertainment out of Cabinet meetings, political pamphleteering and debates over banking and debt relief that took place in an era of powdered wigs and frilly bonnets.

I saw a performance of “Hamilton” at the Pantages Theater in Hollywood on Wednesday evening and found it pleasingly provocative. As important as it is for Americans to have a good understanding of the first generation of people who fought the revolution and invented our country, not everyone finds it easy to relate to the cultural formalities of the 18th-century British colonies. Miranda makes the founding story fresh by dispensing with those formalities — and with the bonnets and wigs, as well.

Like the rap and hip-hop sounds that drive the musical, the social sensibilities of the characters are very much of our time, not of a time long gone. Miranda is not trying to re-create the past; he is trying to highlight commonalities between the founding generation and today’s upcoming generations. He creates a historically accurate picture of Hamilton as a brilliant young man, born out of wedlock and orphaned at a young age, who immigrates to America with a driving ambition to make a name for himself — someone with whom young people with an immigrant background can particularly identify.

As he formulated his production, Miranda’s key decision was to make the race of the actors irrelevant. In the Pantages cast, for instance, the actors playing Hamilton, Burr, Washington and Jefferson are all African Americans. This break with factuality quickly becomes irrelevant in the context of a show that, otherwise, tries to get the major historical details right. Miranda wants his audience — especially the non-white, youthful segment of his audience — to connect with the story of America’s creation, so he gives them hip-hop instead of harpsichords and diversity instead of literal representation.

If the revisionist magic of “Hamilton” works, it will inspire young fans of the musical to dig deeper into the stories of the American revolutionaries and not be put off by the fact that they were mostly white men in waistcoats. Common principles of liberty and justice and the timeless striving of succeeding generations to reshape their world will be the important thing.

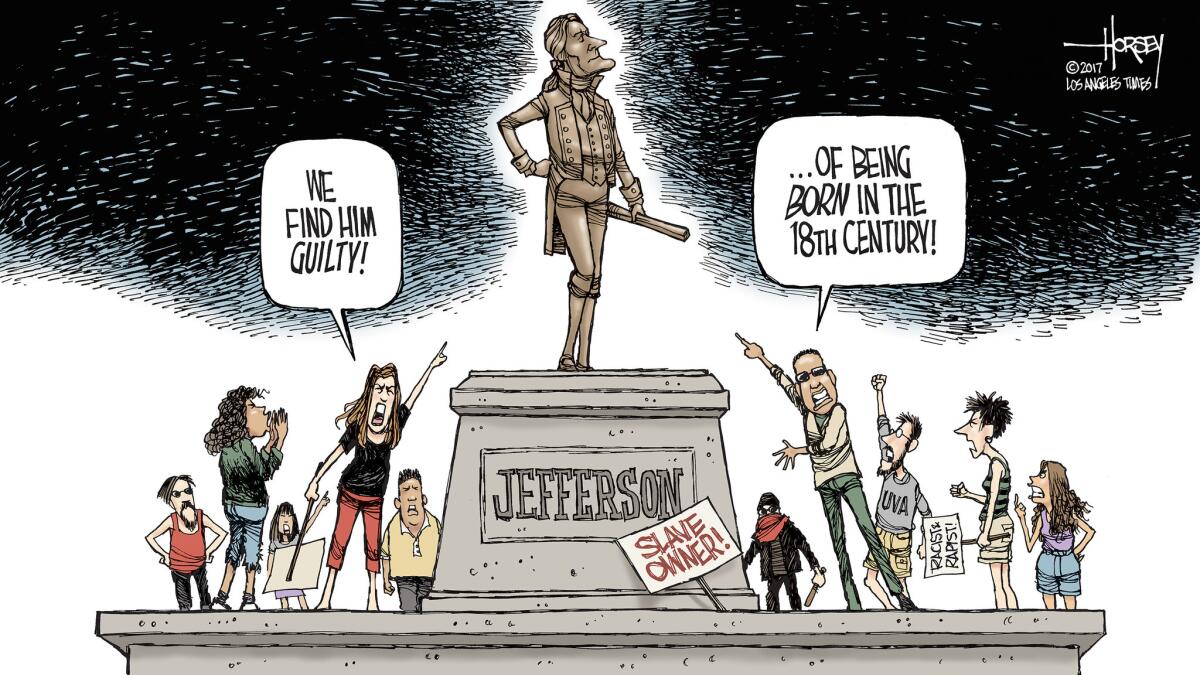

Some folks, however, may have more difficulty overlooking the fraught issue of race. These days, it is nearly impossible to talk about Washington and Jefferson without stating a caveat: They owned slaves. Last week, on the campus of the University of Virginia, protesters covered a statue of Jefferson with a black shroud and accused him of being a “racist and a rapist,” a terribly oversimplified characterization. In the musical, Jefferson is no saint — he is portrayed as a self-impressed politician dressed in a costume Prince could have worn during his “Purple Rain” phase — but, since he is being played by a black actor, his slave-owning is not a factor. For many amped-up activists, that may be taking too much artistic license.

In these fractious days, the story of America is clearly up for grabs. This is nothing new. American history is always being refined and rewritten. The reputations of the various Founding Fathers have risen and fallen and risen again over more than two centuries. In the finale of Miranda’s musical, the last words are given to Hamilton’s wife, Eliza, who lived another 50 years after her husband and worked diligently to resurrect his reputation. Eliza sings, “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?”

The founding story of the United States that Miranda tells with such bold innovation in “Hamilton” is an important one that needs to be kept alive in the consciousness of all Americans. At a moment when our politics are deeply riven, when fights are breaking out beneath statues of Confederate generals and when even the author of the Declaration of Independence is being attacked for being complicit in the sins of his own era, “Hamilton” reminds us that we are all complex and imperfect people. Whatever the color of our skin, our ambitions and longings can lead to scandalous failures, but also to glorious achievements.

That was just as true in 1776 as it is in 2017.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.