Hooray for Sprawlywood

THE pastime of bashing Los Angeles has gained a new urgency lately — or at least a new piquancy. According to those who love to hate L.A., we’re no longer responsible simply for our own ills. We’re doing a pretty good job of ruining the developing world too.

As Andrew Leonard (who lives in Berkeley, my hometown) wrote in Salon after taking his kids on a recent road trip to Southern California, “If the rest of the world continues to follow Los Angeles’ example, we’re all doomed.”

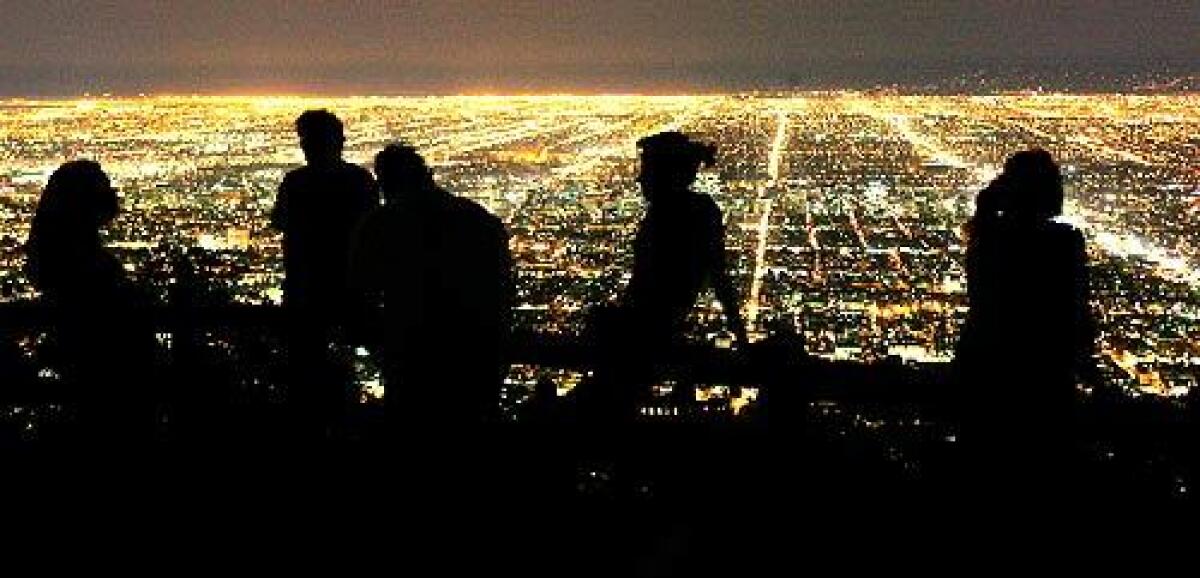

Leaders in India, China and other quickly expanding countries are, indeed, engaged in a mostly futile battle to keep the outer edges of their cities from looking too much like this one.

They unveil 10-point strategies and 15-year plans for sustainable development, but their growing middle classes continue to clamor for McMansions and shiny cars. For the most pessimistic among us, the coming end of the world may best be glimpsed not from American shores but from a gated community just outside Beijing’s sixth ring road.

Before we break out too much apocalyptic rhetoric, though, it might be helpful to consider why the urbanism we perfected in Los Angeles in the 20th century continues to exert such a powerful hold for striving classes everywhere. If there is one concept we have successfully packaged and sold to the world, it’s the idea that it is possible to build a global city out of private amenity.

Prior to the rise of Los Angeles, urban growth was inextricably linked not just to commonality but to at least a modest level of sacrifice; if you gained something significant by moving to a city, you also gave something up. But we attempted to rig the game here, creating a kind of civic casino where the house has no edge. To put it another way, sprawl in Southern California has been more than a geographical reality; it has been a state of mind. A desire, really: for the combination of opportunity, privacy and elbow room.

It was this blend that made Los Angeles so alluring; eventually, it became the basis of our civic brand. This was the place where even a middle-class family could afford a house nestled between front and back lawn, shaded by eucalyptus and palm trees and sitting at a polite remove from its neighbors on either side. The result was the first purely architectural representation of the American dream, a collective aspiration made stucco, topped with a tile roof and punched through with romantically arched windows and doors.

We think of that tableau as essentially suburban, perhaps even quintessentially so. But it was arguably invented within the Los Angeles city limits, where the modest single-family house became a fundamental building block. Where other cities began with the hard kernel of the public sphere and expanded outward, we experimented with a new kind of urban planning, fashioning a whole region almost entirely with the soft tissue of inward-looking residential development.

The amazing thing was that, for the most part, the reality measured up to the marketing pitches. In a city still linked in the public imagination with the idea of illusion, the cinematic trompe l’oeil, there really was (and is) a deep supply of well-built detached houses. There really was a chance for a longshoreman or a butcher to move here with his family and buy one, to come home after work and sit in the backyard, under a trellis sagging with bougainvillea, and sip a glass of beer while watching his kids run around on the grass.

The quiet contentment of that image has its damaging flip side, of course, with which we have increasingly begun to grapple. Because Los Angeles worked so well as a private landscape, and because the freeway system allowed us to take advantage of the ocean even if we lived in Pasadena, or of Disneyland if our house was in the Valley, there never was much of a constituency here for the development of public space.

Indeed, it turned out to be easy for families who had cultivated a private domestic world to do the same when it came to education and transportation, pulling their kids out of public schools and driving around in an automotive cocoon to match the architectural one they so enjoyed at home.

It hasn’t been lost on many pundits that the word that best describes the way Los Angeles has developed — auto-centric — can define a city that revolves around the car as well as one dedicated to the individual.

In a recent essay in the New York Review of Books, Bill McKibben argues that emphasis on the private sphere is a primary symptom of how our relationship to the natural world has fallen out of balance.

“Our sense of community is in disrepair,” he writes, “in part because the prosperity that flowed from cheap fossil fuel has allowed us all to become extremely individualized, even hyperindividualized . We Americans haven’t needed our neighbors for anything important, and hence neighborliness — local solidarity — has disappeared.”

The irony is that even as McKibben writes those words, Los Angeles is in the midst of reassessing its civic structure, a reckoning no less radical for the fact that it is unfolding rather quietly. In backyards and kitchens, in line at Trader Joe’s or the office cafeteria, we are beginning to imagine a very different and more interdependent city.

One of the things that surprised me most when I arrived here two years ago is that many of the people I met, particularly architects and urban planners, seemed to be rooting for gridlock.

If traffic keeps worsening, they reasoned, we would be increasingly restricted to a more circumscribed and pedestrian world, and thus more likely to run into our neighbors on the sidewalk or to complain to our politicians when the grass at the corner park grew patchy or there was fresh graffiti on the walls of the middle school.

Throughout the developing world, the most forward-looking officials have looked closely at the mistakes of Los Angeles, and some are now trying to leapfrog the environmentally damaging sprawl stage and move right to our denser, post-sprawl world.

In China, the government has hoped to improve the region surrounding Shanghai by building nearly a dozen satellite cities, each one meant to act as a center of civic gravity. As the People’s Daily puts it, the goal is to avoid “reckless growth.” But a funny thing happened on the way to the eco-friendly future. Developers realized that because of rising incomes, they could make more money by pitching these new developments at wealthy Shanghai residents, many of whom are just discovering the appeal of overscaled houses and air-conditioned private cars.

The result has been sprawl by other means: a series of developments, modeled mostly on European architecture, serving well-heeled residents who still work in the middle of Shanghai. Sometimes new habits die hardest of all.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com