Unraveling her father’s Cold War secrets

The stranger who called my parents’ house in March posed a baffling question.

Do you know about the reunion? the man asked my mother.

What reunion? she replied.

A get-together of the guys who worked with your husband on the Corona program, the caller said.

The Corona program?

It’s been highly classified — a secret — the man told her, but now we can talk about it. That’s what the reunion is about, he said.

My mother, Jean Cart, listened for a little longer, thanked him and hung up.

Growing up, we never knew exactly what my father did when he left for work. All we knew was that he worked long hours and was sometimes gone for days, leaving my mother with the cryptic salutation: I can’t tell you where I’m going, what I will be doing, who I’ll be with or when I’ll be back. Love you.

A half-century later, a phone call flung open a door to the past. Here at last was a way to find answers to years of questions that a curious little girl had thrown at her father — and kept wondering about to this day.

I started researching Corona. It turned out that quite a bit of information was available. My father and men like him had a hand in creating the world’s first photo reconnaissance satellite during the Cold War and, without the use of sophisticated computers, ginned up a remarkable orbiting tool to gather intelligence on Communist countries, especially China and the Soviet Union.

Although details of Corona were declassified in 1995, the men who worked on it and two subsequent programs — Gambit and Hexagon — were still bound by their 50-year pledge of secrecy until the U.S. government freed them to talk several months ago.

But permission to speak came too late for my father, Hugh Cart. He is 81 and in the last stage ofAlzheimer’s disease. He can’t tell us about his sacrifices or triumphs, or whom he worked with, or what he thought about all those years. He is bedridden and wouldn’t be going to that reunion.

I knew I had to go.

My father attended Louisiana State University on an ROTC scholarship, the first from his bayou family to make it past high school. At 16, he set out for Baton Rouge wearing a white shirt and dark suit sewn by his mother. He carried with him a small suitcase and the heavy expectations of his extended Cajun family.

After he graduated in 1953 with the intention of becoming a teacher, he was expected to return to his home parish, buy a hurricane-resistant brick house, find a French-speaking wife and settle into the humid embrace of south Louisiana. But his life veered another way.

He married a vivacious beauty from Mississippi and together they embarked on an unexpected adventure. He fulfilled his military obligation in the Air Force and was sent to work with guided rockets and special weapons. In the coming decades, the military dictated our family’s movements as my father helped meet America’s urgent need for high-altitude spying.

In those years, intelligence gathering on Soviet military capabilities was primitive.

“Each year on May Day, the Soviet military would drive around Red Square with large missiles on the back of trucks,” said Ingard Clausen, who helped organize the reunion. “American reporters used to count them. The Russians would fly planes and they’d count them too.

“We never knew that most of the missiles were fakes and the Russians just kept flying the same few bombers in a loop over Red Square,” said Clausen, a high-level manager in the Corona program who pioneered the design of the spy satellite’s reentry vehicle. “Over time it became conventional wisdom that the Soviet Union had enough firepower to wipe us out.”

By the 1950s, America’s former wartime ally had become a rival, building a nuclear weapon and regularly spying on U.S. military installations. What intelligence officials thought they knew about Soviet strength was frightening. But it was the fear of what they didn’t know that drove them to action.

In late 1959, President Eisenhower fast-tracked a secret program to gather information about the Communist threats. Named after a Cuban cigar, Corona was an audacious undertaking that went from planning to production in 16 months.

It was a black op, requiring a high-level security clearance. Only about 1,000 people in the country knew it existed, including the engineers from General Electric, Lockheed Douglas Aircraft and Eastman Kodak, and the Air Force and CIA employees who managed it.

The idea was to launch a satellite equipped with a camera 100 nautical miles into space. After the specially built camera took photos, the film would re-enter Earth’s atmosphere tucked inside a shiny, gold-colored capsule. At 55,000 feet, a parachute deployed, slowing the descending capsule, allowing the crew of a C-119 Flying Boxcar to snag it with grappling hooks and winch it aboard.

Corona got off to a dismal start. The first 12 launch attempts failed. An early launch was aborted, Corona veterans said, because a cargo of mice urinated and shorted the electrical power. The mice were on board — ostensibly as a bio-medical experiment — to provide a cover story for the spy mission.

Another capsule landed where no one was looking, near a remote Andean village in Venezuela. TheU.S. Army attache in Caracas rushed to recover the device, which he knew was stamped with “United States” and “Secret.”

According to “The Corona Story,” a declassified history of the program written for the government, two farm workers found the battered capsule and reported it to their employer, who took it home and put it up for sale.

The capsule was hacked into pieces that were pounded into household tools and children’s toys. The radio transmitter was salvaged for parts. A farmer refashioned the parachute’s lines into a harness for his horse.

Corona did eventually succeed, with 144 missions, greatly expanding the nation’s ability to gather intelligence. The first successful flight photographed 1.6 million square miles of the Soviet Union in 1960, providing more overhead photographic footage than all the U-2 spy plane flights up to that time.

Over time, the images revealed that the Soviets were vastly overstating their nuclear arsenal, a discovery that gave U.S. officials the confidence to sign treaties that put limits on the production of nuclear weapons.

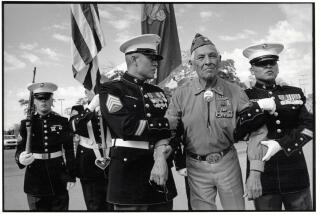

The reunion at a Crowne Plaza Hotel last April was meant to honor those who built Corona. Officials flew in from Washington to thank them for their service to the country. The men milling around the hotel ballroom in King of Prussia, a Philadelphia suburb, may have shuffled behind walkers or leaned on canes, but they had bright eyes and bone-crushing handshakes.

Though they were Cold War heroes who never got parades or medals, they said, without exception, that their work on Corona was the highlight of their lives.

“I’ve pinched myself many, many times,” said Bill Bridwell, my father’s best friend who also worked in the program. “I come from the potash mines in Carlsbad, New Mexico. All the guys at Vandenberg, they were all the same way. They come from dairy farms and ranches. It was just a fairy tale.”

For almost all of my father’s professional life, his work was classified. He was an atomic weapons officer flying out of Maine’s Loring Air Force Base on B-52s loaded with warheads, Bridwell said. When we lived in the desert, he worked on missile fusing mechanisms for General Electric. For the spy satellite program, Bridwell said, my father supervised pre-launch tests and worked on teams assigned to recover the capsule.

In addition to northern Maine and California’s high desert, my father’s work took us to Hawaii, and the outskirts of Albuquerque, N.M., and Yuma, Ariz. Pull out a U.S. map, locate a missile range or a “Danger Live Ordnance!” skull and crossbones, and chances are the Cart family home was nearby.

We moved so much that it is still not uncommon to find green or yellow Bekins inventory tags on the underside of furniture in my parents’ house.

The work was intense and relentless, but the world-class engineers found a way to have fun while staying within the rules. At the Yuma Test Site, they set up bleachers for their children to watch classified missile firings, telling us that they were very large firecrackers. At Vandenberg Air Force Base, the launch day tradition was for the classified team to wear red vests.

After enduring the stress of a launch, the men went drinking at bars in Lompoc or the Vandenberg Inn to celebrate. Their wives knew the drill. By dawn the next day, station wagons driven by yawning women in hairnets would queue up outside the regular haunts, waiting to ferry their Cold War warriors home.

Ed Bryce, 80, was a logistics supervisor at General Electric and responsible for transferring the capsule after GE had done its work. The handoff always took place around 2 a.m. at a restricted military area at Philadelphia’s airport.

The capsule was “a 5-foot cube on wheels,” he said. “Steel containers with combination locks and stamped lead security seals.

“We established fake names and paid everything in cash,” Bryce said, explaining that the money came from a secret account.

Bryce, who has been married 56 years, said his wife understood that he could never explain why he left for work in the middle of the night. “She trusted me,” he said.

It was difficult not to be able to share the struggles and triumphs with their families, the men said. It was Bridwell who told me how good my father was at his job.

“Hugh was highly respected,” he said. “He was project manager in almost every project he was on. He was educated, he was smart, he worked well with people. He got along with everybody. He was a workaholic. That was his problem, that was all our problem. He was a no-nonsense guy but a hell of a lot of fun to work with.”

Bridwell and my father have always had a special camaraderie and still live near each other in Scottsdale, Ariz. “I never had to look behind me — Hugh had my back,” Bridwell said.

When I visited my parents after the reunion, I sat by my father’s bed and held his hand and told him that the endlessly curious daughter who wanted to know everything had been researching his life.

I told him: We know now what you did all those years. No more questions, dad.

VIDEO: Cold War warriors tell their stories

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.