War Could Pivot on U.S. Hearts and Minds

With more and more U.S. troops dying in Iraq, emotions on the American home front are increasingly conflicted.

In Crawford, Texas, a tent city of antiwar families sprung up around a mother who lost her son in the war and wants to speak to President Bush. In Washington, several prominent Republicans are demanding troop withdrawals next year.

Just as forcefully, the sister of an Ohio soldier killed recently says the U.S. must continue to fight so his death will not have been in vain. Back in Crawford, pro-Bush demonstrators are trying to outshout the antiwar contingent.

Is this a breakthrough moment, when public sentiment shifts dramatically against a conflict, as it did during the latter part of the Vietnam War? Or is it just a low point in a war that ultimately the country will be proud to have waged?

Watershed events usually are identified by scholars years after a war ends. Still, elements of the present conflict have echoes of previous wars -- and many historians believe a comparison with those moments can shed light on the American home front today.

“When Americans see the war that is being fought as somehow connected to larger purposes, that makes the war and its sacrifices more palatable,” said Andrew J. Bacevich, a Vietnam veteran and professor of international relations at Boston University.

“If Americans begin to see that a war does not connect to larger purposes, then their willingness to sacrifice and continue supporting an administration declines. In short, we want our wars to mean something.”

There were few misgivings about the need to fight World War II because America had been attacked at Pearl Harbor. Most Americans also were eager to stop Hitler’s Germany from taking over all of Europe.

The same cannot be said of the Iraq war because of the debate over whether Saddam Hussein’s regime had any link to the Sept. 11 attacks. The futile search for weapons of mass destruction also made skeptics of many on the home front.

“World War II had lots of discouraging moments, but almost everyone saw that it had to be carried out to its conclusion,” said historian Geoffrey C. Ward, whose 14 books include one on the Civil War.

“The difference here is that increasing numbers of people aren’t sure it is worth it.”

Vietnam may offer a better analogy, because the underlying argument for that conflict -- the need for the United States to fight communist expansion -- gradually gave way to a belief that the war was bogged down in a quagmire that was killing thousands of Americans a year. The public can rapidly lose faith in leaders if it does not think a conflict is winnable.

When public opinion tilted against the Vietnam War after the Tet offensive in 1968, President Johnson chose not to seek reelection.

Yet the comparison has limits.

There was a national draft during Vietnam that caused millions of parents to fear that their sons could be sent to war. That war also spawned a protest movement that seemed to aim much of its anger at U.S. forces. The Iraq war is being fought by an all-volunteer army, and most critics make a point of condemning the war, not the warriors.

Still, the same fears of a morass are slowing surfacing about Iraq, some historians say.

“I think we’re looking at a watershed moment now, because this Iraq war stands in the shadow of the Vietnam War and all the failures we associate with it,” said Robert Dallek, a biographer of Presidents Johnson and Kennedy.

“More and more people have the feeling that we’re trapped in quicksand in Iraq, just as they did in Vietnam, and I don’t see how Bush can regain enough credibility to say things aren’t that bad,” Dallek said. “He sounds like Johnson did, always saying there is light at the end of the tunnel, and the fact is people don’t believe him.”

Public opinion might swing in favor of the war if victory is in sight. Iraqis are expected to vote in October on a constitution, and Hussein’s trial may begin within several months. Both events could play a key role in building support for the war.

But, as in Vietnam, the initial American effort to fight a conventional war in Iraq has given way to the deadly unpredictability of a guerrilla war.

The Bush administration has repeatedly said that the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were necessary after the Sept. 11 attacks. Bush also has consistently maintained that sacrifices are needed to win the global war on terrorism.

Those arguments continue to persuade some Americans, said David Gergen, a public policy professor at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and a former advisor to four presidents.

“I think people are really worried that if we get out of Iraq the end result will be worse, because of the fear of terrorism,” Gergen said. “That has sustained the president.”

Twenty-nine months into the conflict, that support is faltering. In a recent USA Today/CNN/Gallup poll, 54% of respondents said the war was a mistake. The same poll showed that 57% said the war had made this country more vulnerable to terrorism. When the war began in March 2003, a CNN poll found support from 71% of Americans.

Attitudes toward the war might be different if the public saw that it was being fought with clear goals, said Stanley Karnow, author of “Vietnam: A History.”

“In a conventional war, like World War II, the Army lands in Normandy in June; it liberates Paris in August and starts marching on Berlin,” he said. “The folks at home are sticking pins in maps and they all say, ‘We’re making progress; we believe in this fight.’ ”

In Iraq, Karnow added, “there is growing dissent because we don’t know what the standard of victory is, or if we’ll ever really achieve it.”

The same confusion surfaced during Vietnam, and many critics blamed the media for fueling public dissatisfaction, especially with graphic coverage of the Tet offensive.

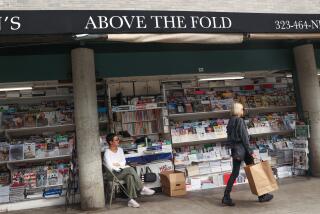

The Iraq war does not serve up as many unsettling images. But the coverage may be feeding a different kind of discontent.

By the Pentagon’s design, the public sees few pictures of dead U.S. troops. While this approach might promote a sanitized view of the war, it could undercut the Bush administration’s case for making the conflict a national crusade, said William O’Neill, a Rutgers University professor of U.S. history.

World War II newsreels showed dead U.S. troops washing up on Pacific beaches, O’Neill said. The effect was that “Americans at home understood the dramatic sacrifices that were being made for them, and why they all had to play a role in fighting the war.”

O’Neill called the Pentagon’s refusal to allow pictures of coffins “mystifying, because the public can handle this, and it promotes great sympathy.”

Others say that public sentiment has shifted against the war because the media have manipulated emotions by focusing on sad stories about individuals and their grieving families.

This would not have been possible in previous wars because the American death toll was too high, said military historian Frederick W. Kagan, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a former instructor at West Point. In Vietnam, 58,169 troops died; in Iraq, 1,862 had died as of Saturday. At some point, media coverage becomes a national Rorschach test. People with differing views of the war see what they want to see.

Attention has focused recently on an Ohio Marine battalion that has lost 47 members since March. The deaths of so many troops from a single area jarred many Americans.

That kind of carnage was commonplace in the Civil War, and newspaper coverage marshaled public support, said James Marten, author of “Civil War America: Voices From the Home Front.” The stories provided “a link between the home front and the war,” making civilians feel more connected to the combat.

Ultimately, military officials give little weight to public moods as they plan their strategies.

It is doubtful, for example, whether military leaders are keeping tabs on Cindy Sheehan, the mother who set up camp Aug. 6 near Bush’s ranch, said Tad Oelstrom, a retired Air Force general who directs the national security program at Harvard’s Kennedy School. On Thursday, Sheehan traveled to Los Angeles to be with her mother, who had suffered a stroke. Sheehan said she intended to return to Crawford soon.

“For the general in the strategy room, it is not about public opinion, and it should not be about public opinion,” Oelstrom said. He said senior military personnel were probably paying little attention to “what you would say from a media standpoint is a turning point, because they continue to see progress being made.”

History shows that military leaders ignore national morale at their peril. A public that believes in a war’s goals will put up with unimaginable suffering; a nation strongly divided over escalating deaths might not be able to sustain such an effort.

If and when the Iraq war reaches a turning point, the catalyst may be something less than a spectacular victory or an overwhelming defeat, said Michael Keane, a military tactics expert at the USC business school who was embedded with the 101st Airborne Division in Iraq.

The outcome, he said, may turn on a slow rupture of faith.

“This war is just a grind of a conflict,” Keane said. “And it is very difficult to maintain morale both in the field and at home.”

Getlin reported from New York, Mehren from Boston.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.