The ‘sheik’ of Syria’s rebellion ponders its obstacles

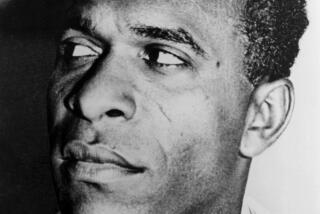

DAMASCUS, Syria — He doesn’t have a cellphone and doesn’t use regular phones. He avoids his home and mostly ventures out under cover of night, a cap pulled low on his head to conceal his identity.

“For 11 months, I have not been in a public place, not in a restaurant or a cafe,” Yassin Haj Saleh, a former political prisoner, said as he arrived at a previously agreed-upon rendezvous spot as darkness fell.

Despite his clandestine existence, Saleh is a prominent Syrian dissident, a prolific writer and columnist with a wide following both in print and on the Internet. One young opposition activist calls him the “sheik” of Syria’s yearlong rebellion.

Unlike some high-profile Syrian dissident exiles featured in opposition conferences abroad, Saleh spent 16 years imprisoned for his views and has remained in Damascus, the capital, daily risking arrest.

“He’s got total credibility: He was in prison and is part of that crowd still inside Syria, not living outside the country for 30 years,” said Joshua Landis, who directs the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma and writes an influential blog on Syria.

Syria’s opposition includes many disparate currents, among them secular liberals such as Saleh, Islamists, Kurdish nationalists, Web-savvy youths and urban and rural guerrillas. While at odds on many issues, they generally are united on one objective: the need to oust the government of President Bashar Assad.

“The worst possibility for our country is that the regime stays in power,” Saleh, 51, said in an interview at a safe house here. “Anything else is less bad.”

Still, the opposition is a fractious network riven by internal disputes. Last month, several prominent dissidents split from the best-known umbrella group, the Syrian National Council, complaining that it was a front for the exiled Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist movement viewed warily by many secular Arabs.

Saleh, who describes the Syrian National Council’s overall performance as “depressing,” has reluctantly come to accept the rebellion’s increasing militarization. But he bemoans the lack of a centralized command structure and discipline among the proliferating insurgent bands.

“None of us asked for it,” Saleh said of the Free Syrian Army and other factions that have taken up arms. “The problem is how to organize these groups.”

He believes the lack of unity and organization among armed factions and political groups are obstacles to the revolt progressing faster, as is a lack of “new” thinking.

What is most needed, he says, is fresh thinking about a dynamic, grass-roots upheaval that emerged with a vitality that shocked him and other longtime dissidents, both in Syria and outside. Too many Syrian intellectuals, he said, are still shackled to Arab nationalism and other Cold War-era ideas and political ideologies.

“It’s not a matter about living abroad and inside,” said Saleh, a dapper figure in a sweater and chinos, far from the image of the harried, bedraggled man on the run. “It’s a matter of traditional mentality that cannot deal with new facts and new generations and a new sense of life.”

Last spring, when the Syrian revolt was in its nascent, largely protest, phase, Saleh was upbeat and declared that his country was finally poised for a dramatic shift.

A year later, thousands have lost their lives in an uprising that has morphed into armed insurrection with no end in sight, dismaying many who preferred the path of peaceful revolution.

“In the first few months,” Saleh acknowledged, “it was easier to have a clear vision.”

As the death toll soars, some activists in the Syrian capital have become disillusioned, fearing a slide toward catastrophic civil war and sectarian bloodletting. Saleh, however, remains an optimist, while voicing deep fear of deepening divisions.

“After 11 months of killing, there is kind of a political refuge being taken to God and to religion,” he said.

He laments a “deep grudge” stoking sectarian enmities in Syria, long a secular state where, under the Assad leadership, minorities were tolerated even as political dissent was crushed.

While supporting continued mass protests, Saleh now thinks that demonstrations alone are unlikely to topple a president backed by a loyal security apparatus installed by his late father, Hafez Assad, a ruthless practitioner of Middle East power politics.

“There is no chance it will be like in Tunisia,” said Saleh, referring to the North African nation where the inaugural “Arab Spring” revolt chased longtime strongman Zine el Abidine ben Ali from power, with minimal bloodshed. “It will be more violent and chaotic.”

Saleh was imprisoned as a 19-year-old medical student, he says, because of his membership in a communist group viewed as a threat by Hafez Assad’s regime. He spent the last year of his imprisonment in Syria’s notorious Tadmor prison.

“Books saved me physically and mentally,” Saleh told Reason magazine in a 2005 interview. He taught himself English while in prison. “If it were not for the books, I would have most certainly been crushed. Now I live on what I learned in prison.”

He was released in 1996, when he was 35, and completed his medical studies in Aleppo, but he never worked as a physician. He opted for the life of writer and political dissident, a parlous existence in the Assads’ Syria.

Facing censorship at home, Saleh found a forum in Arabic-language media in neighboring Lebanon, always more open to freedom of expression. Nowadays, he spends much of his time reading, writing and on the Internet, where he is an avid email correspondent and Facebook commentator. He writes a regular column in Al Hayat, a leading pan-Arab newspaper.

He sees no easy resolution of his country’s crisis, especially in the face of the government’s relentless crackdown, the escalating casualty count and the deep fissures that have opened up in Syrian society.

“The longer the revolution goes on,” Saleh said, “the more divided the people become.”

Sandels is a special correspondent. Times staff writer Patrick J. McDonnell in Beirut contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.