As a new pope is chosen, Latin America hopes for more sway

MEXICO CITY — They represent the region with more Roman Catholics than any other. And their to-do list for the next pope is a long one.

Next month, 19 cardinals from Latin America will be among the 117 from around the world expected to be eligible to participate in the secret meetings to choose a replacement for Pope Benedict XVI.

And though the chances for a Latin American pope being elected are a long shot, regional leaders are hoping to have more influence than before both in the selection process and in addressing many of the major problems facing the church in general and Latin America specifically.

Among them: the growing secularism and corruption of faith that Benedict so frequently complained of and the church’s sex abuse scandals, involving clerics in Mexico, Chile and Brazil.

Issues of particular concern for Latin America include the evangelical religious faith that has been rapidly siphoning off church members and the lack of fervor for the current pope.

“Latin Americans have for a very long time felt they should get more say in choices and policy decisions; they feel that because of their size, they should have more influence at the Vatican,” said Margaret E. Crahan, an expert on the church at Columbia University’s Institute of Latin American Studies. “But the Europeans still dominate.”

Many Latin American Catholics never warmed completely to Benedict, in part because of his terse style and in some cases because of his conservative ideology. He remained a distant, rigid figure to many, despite two high-profile visits to the region, and they speak now of hope for a new pope who would be more personable and accessible.

The next pope “will have to take the church from this image of paralysis … and find a clear, agile way to preach the Gospel,” said Hugo Valdemar, spokesman for the Archdiocese of Mexico City, the world’s largest.

Contrary to popular opinion, and perhaps wishful thinking, cardinals who gather in the Sistine Chapel for the pope-choosing conclave are not believed to generally vote in geographic blocs. Latin American cardinals, like their counterparts the world over, tend to seek guidance from members of their same order, peers worldwide who are friends, and, especially, cardinals based in Rome who are most familiar with the workings of the Vatican and in the best position to promote or thwart contenders.

In the last conclave, in 2005, the Latin American delegation failed to rally behind a single candidate. Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani of Peru probably looked to the only other Opus Dei cardinal, Julian Herranz of Spain. There were reports of a last-minute surge by Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina, a Jesuit who also had strong conservative credentials and who would have drawn support from two groups that at times are at odds, but not in the numbers needed.

The church hierarchy in Latin America has also become much more conservative in recent decades. Benedict and his predecessor, John Paul II, left a distinct mark on the church in this region, cracking down on dissent and replacing liberal prelates with conservatives. Much of that policy was aimed at stemming the pro-left liberation theology movement that began to spread in Latin America in the 1960s and ‘70s and at bringing the clergy and laity back into line with orthodox teaching.

The result today for many Catholic worshipers in Latin America — though certainly not all — is a church hierarchy out of step with their pressing daily problems. Some still hanker for the more progressive activism that was nurtured by liberation theologists. Moreover, despite their overall moral and theological conservatism, the “princes” of the church do not speak in one voice, depending on the internal dynamics of each country; for some, issues of social justice do remain a priority, while others must deal with violence or other overarching challenges.

The reputation of the church in Latin America was badly hurt by sex abuse scandals, mostly notoriously the case of the late Father Marcial Maciel, the once-revered Mexican founder of an ultra-conservative religious congregation known as the Legion of Christ. Maciel was a favorite of the Vatican and especially of John Paul before it was revealed that he had sexually abused seminarians for decades, fathered at least three children by two or more women and was a drug addict. Benedict finally removed him from duties in 2006 shortly before his death and ordered the organization overhauled.

The Maciel case cast a pall over Benedict’s pilgrimage to central Mexico last year, when abuse victims and their supporters staged competing events and demanded a meeting with the pontiff. Although Benedict has conferred with sexual abuse victims in some of his voyages, he did not do so in Mexico. It is not clear whether the conservative local church hierarchy, some of whose senior members had also protected Maciel for years, made the petition known to the Holy See.

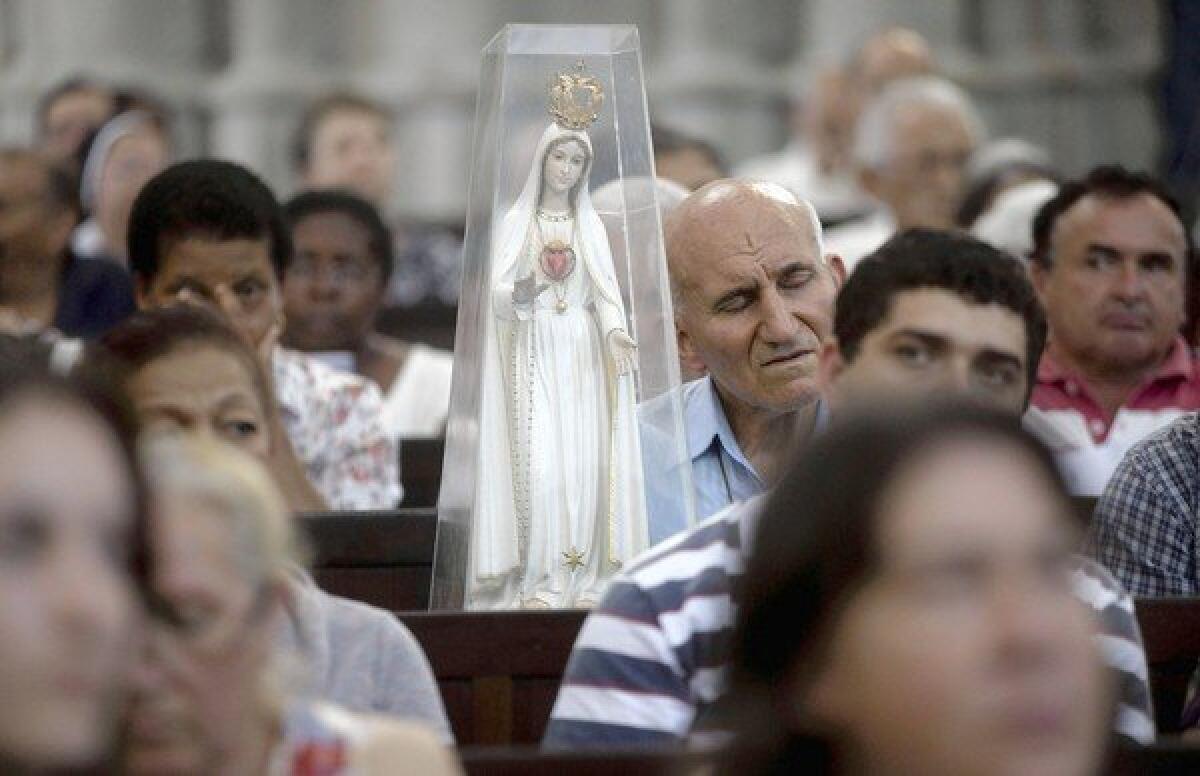

In Mexico and Brazil, two of the three Latin American countries where Benedict has set foot — the other was Cuba — the mood last weekend seemed to overwhelmingly favor a different kind of pope.

“The church needs renewal,” Edson Jose de Souza, 43, who runs a glass business, said outside the Nossa Senhora de Fatima e Santo Amaro church in the Brazilian beach town of Guaruja. Mass was packed, with worshipers in surf wear and older couples fanning themselves, all spilling out into the street from the chapel.

“Over the last few decades we’ve suffered huge losses of the faithful to other religions, especially the evangelical churches. We need to rescue them,” said De Souza, who is a member of the Catholic Charismatic Renovation movement, a lively current that has arisen in Brazil to challenge the appeal of the raucous evangelical services.

On the western outskirts of Mexico City, at the Santa Rosa de Lima church in a working-class parish, many of the faithful expressed similar misgivings.

“With all the problems the church has, if they don’t do something it will seriously decline,” said Refugio Bonilla, a 39-year-old teacher. “We believers will always be here, because we have faith and that’s how we were taught. But the new generations, they are losing interest.”

At the upscale San Agustin Church (where the son of the world’s richest man got married two years ago), in Mexico City’s affluent Polanco neighborhood, Alexia Alvarez, 26, was joining a steady parade of worshipers filing in for Mass. She wore surgical scrubs from the hospital where she works as a gynecologist.

“The other one [Pope Benedict] wasn’t bad, just very old,” she said. “It is time for other priorities, to look here to the poor countries and speak to them.”

Benedict had an especially hard act to follow in Mexico, which hosted the much-beloved John Paul five times. In the gift shop at San Agustin, picture cards of most every saint and Catholic icon imaginable were on sale, including John Paul. But there was not a single one of Benedict. “The people don’t ask for Benedict,” the sales clerk confided.

At next month’s conclave, the number of Latin American cardinals who will vote is one fewer than the 20 electors who participated in choosing Benedict nearly eight years ago. By contrast, there were also 20 Italians in 2005 but 28 this time around.

Jennifer Scheper Hughes, a history professor at UC Riverside, said the voice of Latin American bishops in Rome has weakened considerably since its heyday during the Second Vatican Council period of reforms in the 1960s. As they look to the selection of a new pope, she said, the faithful in Latin America today “are longing for something else more pastoral, but they are also more cynical and less hopeful that things will change.”

Some analysts think Latin American prelates still manage to wield significant influence; in the curia today, for example, Argentina’s Cardinal Leonardo Sandri (born to Italian parents) is considered a talented diplomat, is in charge of the Congregation for the Oriental Churches and is often mentioned as a potential pope, and Cardinal Joao Braz de Aviz of Brazil is the prefect in the curial department that oversees institutions dedicated to consecrated life. Although Braz de Aviz is not usually listed as a papal candidate, his countryman Cardinal Odilo Pedro Scherer, archbishop of Sao Paulo, does make some wish lists.

“There has been an effort to try to involve voices in the curia” even if the diversity of the College of Cardinals has diminished compared with 2005, said Matthew Bunson, editor of the U.S.-published Catholic Almanac. This conclave “is probably the most wide open of recent memory.”

Although a Latin American pope would be a surprise, the prospect certainly fires the imagination and appeals to many in the region as a nod to the church’s size here, as well as its problems, hopes and potential.

“Latin America clearly has the gift of the largest number of Catholics, and we are obliged to live up to that faith,” Venezuela’s Cardinal Jorge Urosa Savino told a Caracas newspaper. “If we were to be blessed with a pope from Latin America, well, how marvelous! But it is not necessary for the future of the church.”

Cecilia Sanchez, a news assistant in The Times’ Mexico City bureau, and special correspondent Vincent Bevins in Guaruja contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.