Spain’s Basque Country bouncing back quickly from recession

BEASAIN, Spain — The Spanish countryside is littered with unfinished condos, stillborn reminders of the country’s disastrous construction boom gone bust. But the verdant valleys and Atlantic cliffs of the northern Basque Country are virtually free of that blight.

Why? For decades, terrorist attacks by the Basque separatist group ETA meant no one wanted to build here.

Now with a cease-fire that’s held for two years, the region is casting off its reputation for terrorism and garnering one for something else: Economic growth unseen in the rest of Spain.

“With the threat of terrorism, this was not a very attractive place for people to come,” said Jose Luis Curbelo, general manager of the Basque Institute for Competitiveness. “So housing was an activity to house people, rather than to speculate. The real estate sector here was a normal activity. It was not totally overgrown like in the rest of the country.”

That’s helped the Basque Country bounce back from recession quicker than the rest of Spain, which now lies at the heart of Europe’s debt crisis. Spain is struggling to erase bloated budget deficits and avoid an international bailout that could destabilize the entire Eurozone.

Because jobs weren’t clustered in one industry gone bust, the Basque unemployment rate is less than half that of the nation’s 25%. Spain’s economy is forecast to shrink by nearly 2% next year, but the Basque Country hopes to register growth in 2013. And though its 2.2 million residents make up only 4.5% of Spain’s population, they contribute nearly 10% of its exports.

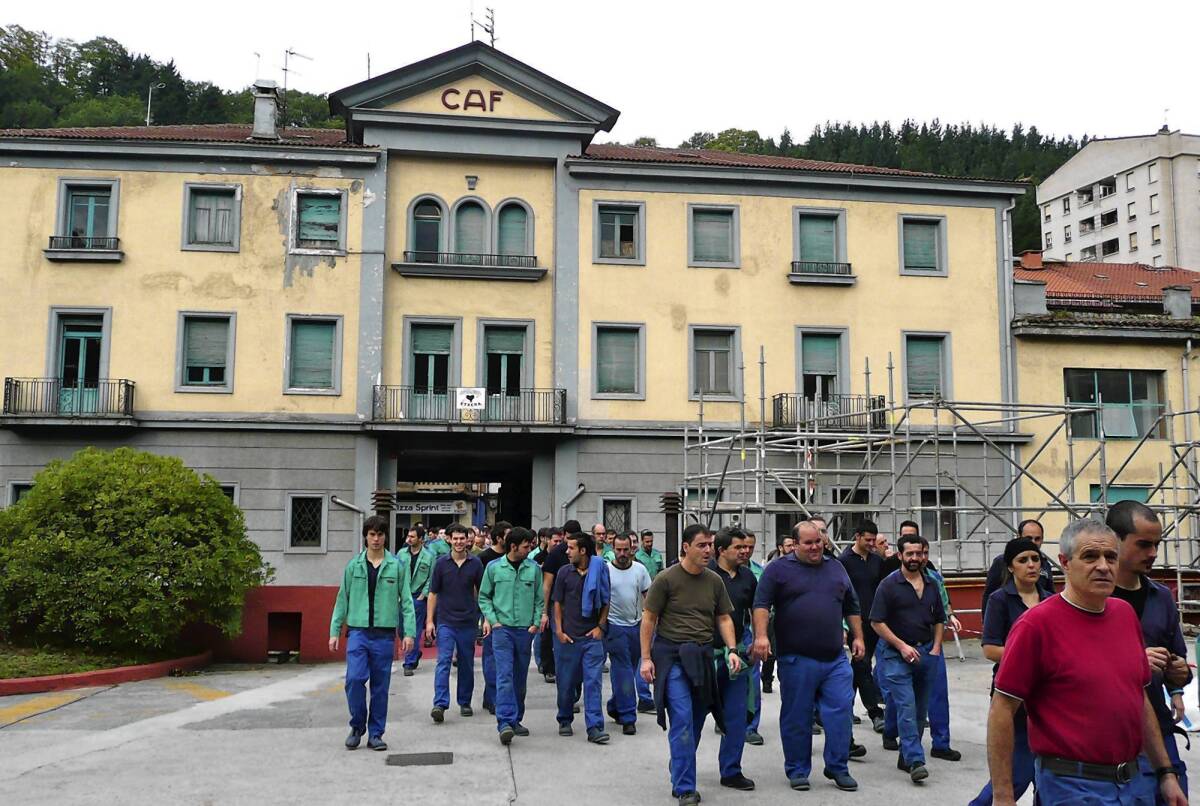

Take the railway manufacturer CAF, a nearly 100-year-old company headquartered in this Basque-speaking mountain village near Spain’s north coast.

More than three-quarters of CAF’s sales are abroad, unfettered by Spain’s economic crisis, and the company has posted operating profits of 10% or more for the last five years. It makes train cars for Amtrak, the Washington metro and light rail systems in Sacramento, Houston and Pittsburgh, plus projects in Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Hong Kong and Mexico, among others.

It may be lucky happenstance that CAF’s business was diversified abroad when Spain’s debt crisis hit. But its geography, and its history, didn’t hurt.

The Basque Country is rich in natural resources, particularly coal and iron ore, that at one point in the 19th century made it one of the world’s largest steel producers. And for centuries, it was easier for Basque traders to sail directly north to Britain than to travel by horseback over nearly 9,000-foot mountains that separate the region from the Spanish capital, Madrid.

“They had mines there. There was steel, and there was coal. And they were very close to England,” said Fernando Fernandez, an economist at Madrid’s IE Business School. “So they were exposed to the Industrial Revolution, with all that entails, much earlier than other regions of Spain — much earlier.”

At CAF’s Beasain headquarters, factory workers in jumpsuits file through a stone archway each morning, lunch pails in hand, in a scene reminiscent of the hilly industrial north of England in the 1950s, before much of the industry there moved abroad. In the Basque Country, it has stayed.

That can be attributed in part to a vocational education system that was largely tossed out in the rest of Spain, because some associated it with the administration of Francisco Franco, the dictator who ruled Spain for nearly 40 years until his death in 1975. The Basque Country kept the system, and has flourished under it.

“You had a company, a factory, and nearby the factory was a school — a vocational school — to train workers. And that was from the 19th century on,” Curbelo said. “Vocational education is something that has always been highly valued by the [Basque] population, by the society. And the companies had always relied on the workers they were training nearby.”

In the 1980s, as Spain’s wealth grew, “there was this crazy idea that to be modern, you need to have a university degree, and there was like a negative perception if you didn’t have one,” Curbelo said. “But in the Basque Country, probably because the blue-collar workers had good salaries and living standards, there was no negative attribute to not having a university degree.”

A majority of Spaniards go to university, which is heavily subsidized by the state. But the jobless rate for young graduates tops 52%.

Companies such as CAF reap the benefits of Basque vocational training, which includes apprenticeships similar to those in Germany, Europe’s largest and strongest economy. The German unemployment rate is just above 5%.

“In the Basque Country in general, it’s not very difficult to find a person with the profile you need for a particular job. I would say that almost all the time, you can find somebody ready to come into the company and start working the next day,” said Aitor Galarza, CAF’s director of quality and strategic planning. “It doesn’t happen that easily with our factories in the south of Spain.”

Galarza has another theory about the Basque Country’s productivity: The region gets more than 200 days of rain a year.

“So when you’re working at your factory, you never think of going to the beach in the afternoon, or just having fun,” he said, laughing. “That also moves your mind to the work you are doing.”

Frayer is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.