Barbara Adams dies at 77; caretaker of handmade Lloyd Wright house

Barbara Adams viewed herself as a caretaker of a “little part of Valley history” -- 676 square feet, to be exact.

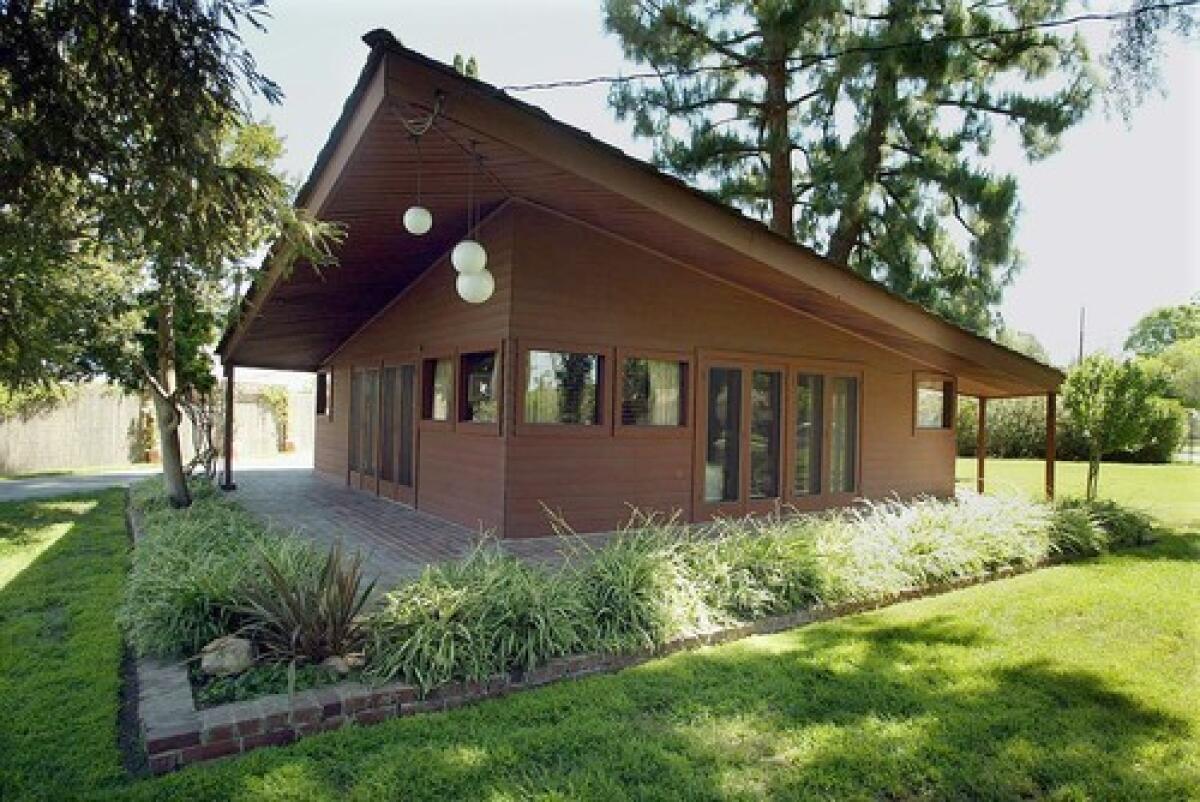

That was the size of her Reseda home, designed in 1939 for her husband’s family by architect Lloyd Wright, reportedly with input from his famous father, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Months after her husband, Bob, died in 1995, Adams felt a responsibility to preserve the building and its story and successfully campaigned to have the house designated a historic-cultural landmark.

Adams, 77, died of cancer Jan. 23 at the Reseda home, which she had lived in since 1986, said her daughter, Kerry Scott.

Architect Eric Lloyd Wright, who as a child visited the site with his father, Lloyd, during construction, called it “such a simple little house, unpretentious. Yet it has a lot of character, and she recognized that. It was wonderful how she took care of the house.”

Adams’ father-in-law, Bill, was a machinist familiar with Frank Lloyd Wright’s philosophy that “every working man should have a home he can build himself,” she told The Times in 2003. So he wrote to the architect and effectively dared Wright to design an economical and practical house that he and his college-age son, Bob, could build with their own labor.

According to family lore, Frank Lloyd Wright responded that he was too busy but had sent some ideas to his son, Lloyd, who lived in Los Angeles and would go on to design the Wayfarers Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes.

Attracted to the idea of designing something simple that could be built on a budget by the owner, Lloyd took the job, Eric Lloyd Wright said. Plans were drawn for a square house, 26 feet wide, with a roof angled to provide relief from the San Fernando Valley’s intense summer heat.

The Adamses took four years to build the two-bedroom home on a half-acre lot at what is now Valerio Street and Tampa Avenue, which was then a single-lane dirt road.

Architect and family ended up parting ways over what Lloyd Wright had dubbed the Mat House -- for the thatch-like roof he’d proposed -- when the Adamses nailed down cedar shakes instead. The architect collected only $50 of his $125 fee. The home was built for $1,351, or nearly $17,000 in today’s dollars.

“She loved living in the house,” Scott said of her mother, a civic activist who also “loved educating people about this little gem that was hidden in the Valley.”

A Los Angeles native, Barbara Adams was born Barbara Lorraine Kerr on Dec. 29, 1931. Her family ran Kerr Travel agency on Wilshire Boulevard.

After attending UCLA, she settled in the Valley with her first husband and had two children. Divorced after about a decade, she pursued a career in public relations and had a brief second marriage.

Friends reintroduced her to Bob Adams, who had been her neighbor. His parents moved to a retirement home shortly before their deaths in the late 1980s, and she and Bob moved into the Wright house around the time they married.

Many of the home’s features “are better seen than described,” including “the influence of a bottle of vodka on the building of the fireplace,” Barbara Adams wrote in “Background Tales,” a history that she handed out to architecture students and others who periodically toured the house.

Because her in-laws had been reclusive, the couple found “many neighbors had questions about this unusual home,” Adams wrote, noting that Bob wanted to place a marker out front “as a memorial to his parents and to inform the curious.”

A plaque was finally installed after she urged the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission to designate the building a historical-cultural landmark.

The status, granted in 1996, means the house cannot be torn down or significantly changed without city permission.

“The little house has survived without much change, but as a witness to many surrounding changes,” Adams wrote. “The residents have changed, but their shelter has not.”

The family is considering selling the home or donating it to an organization that would preserve it.

In addition to her daughter, Adams is survived by a stepdaughter, Karen Thrasher; a stepson, Phillip Adams; six grandchildren; and a number of great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.