Blake Edwards dies at 88; ‘Pink Panther’ director was master of slapstick comedy

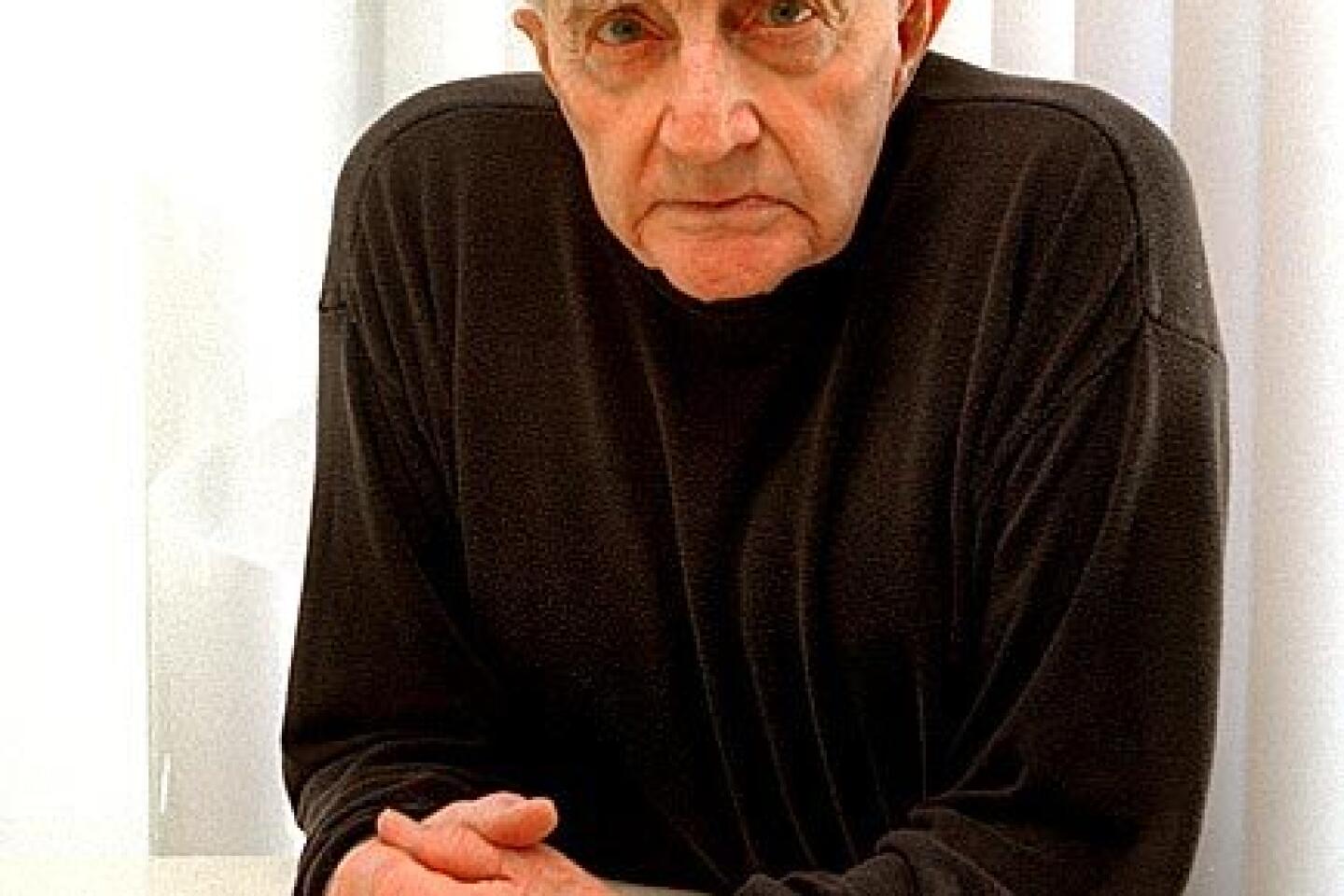

Blake Edwards, a writer-director who battled depression in his personal life yet was known as a modern master of slapstick and sophisticated wit with hit films such as the “Pink Panther” comedies, “10” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” has died. He was 88.

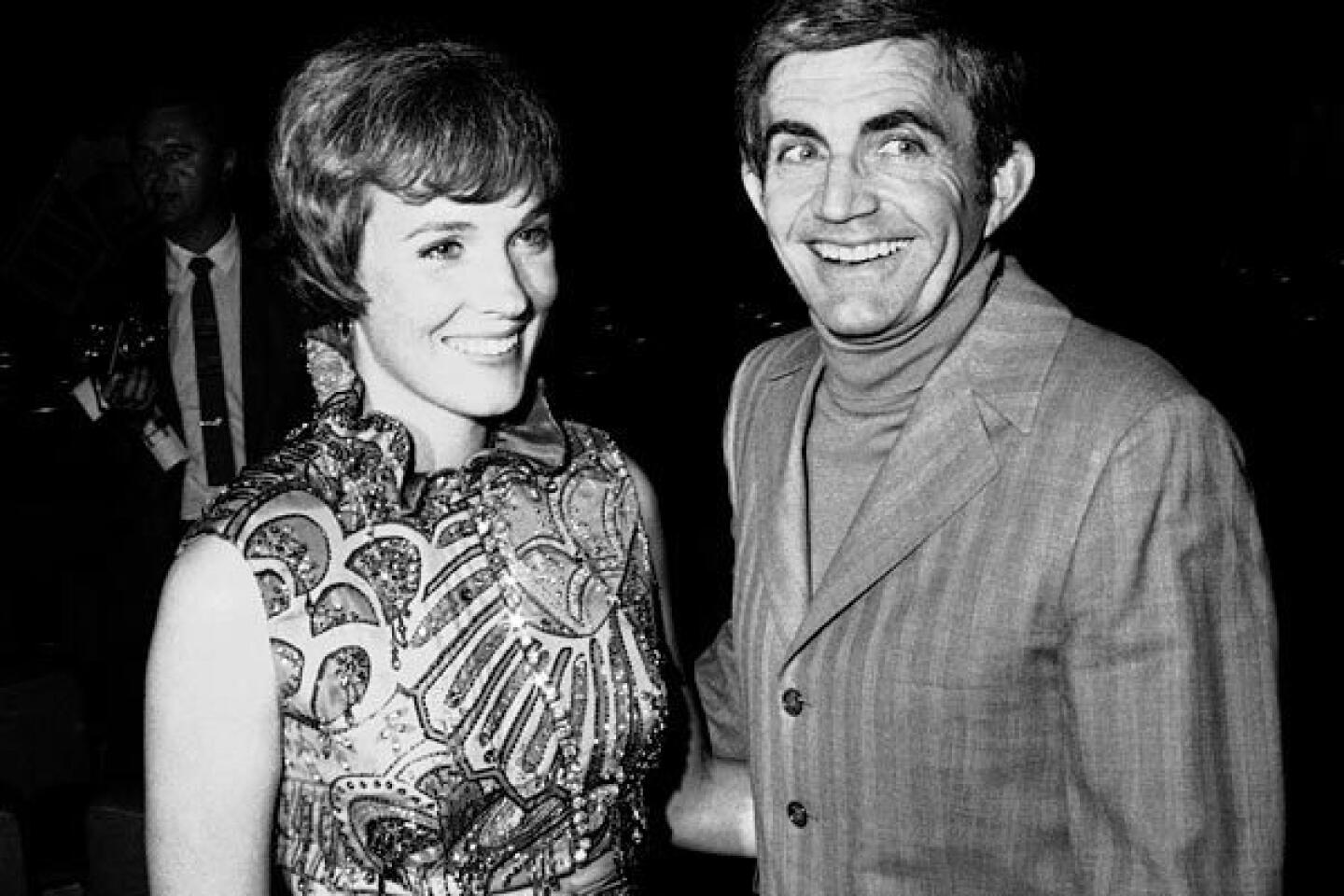

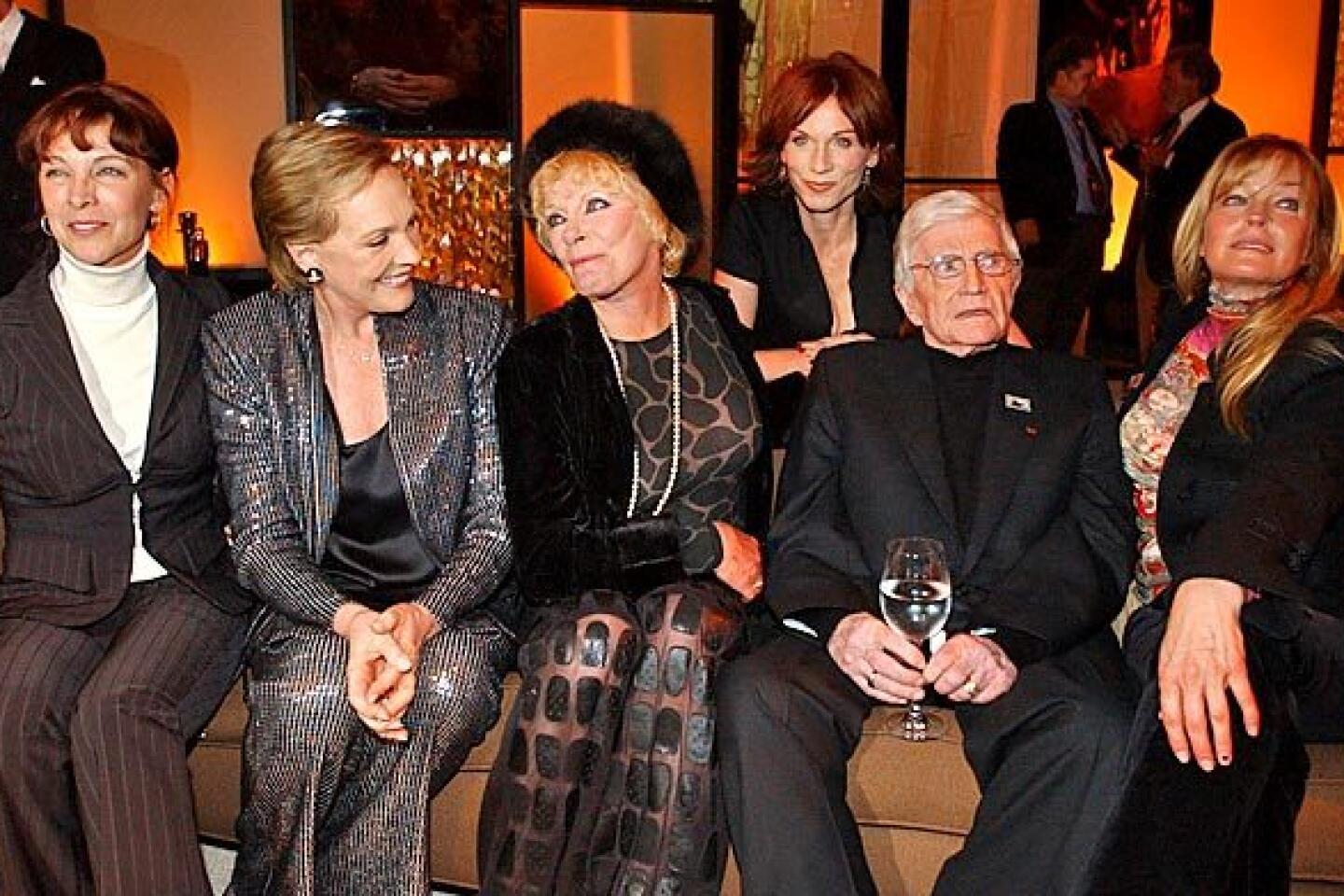

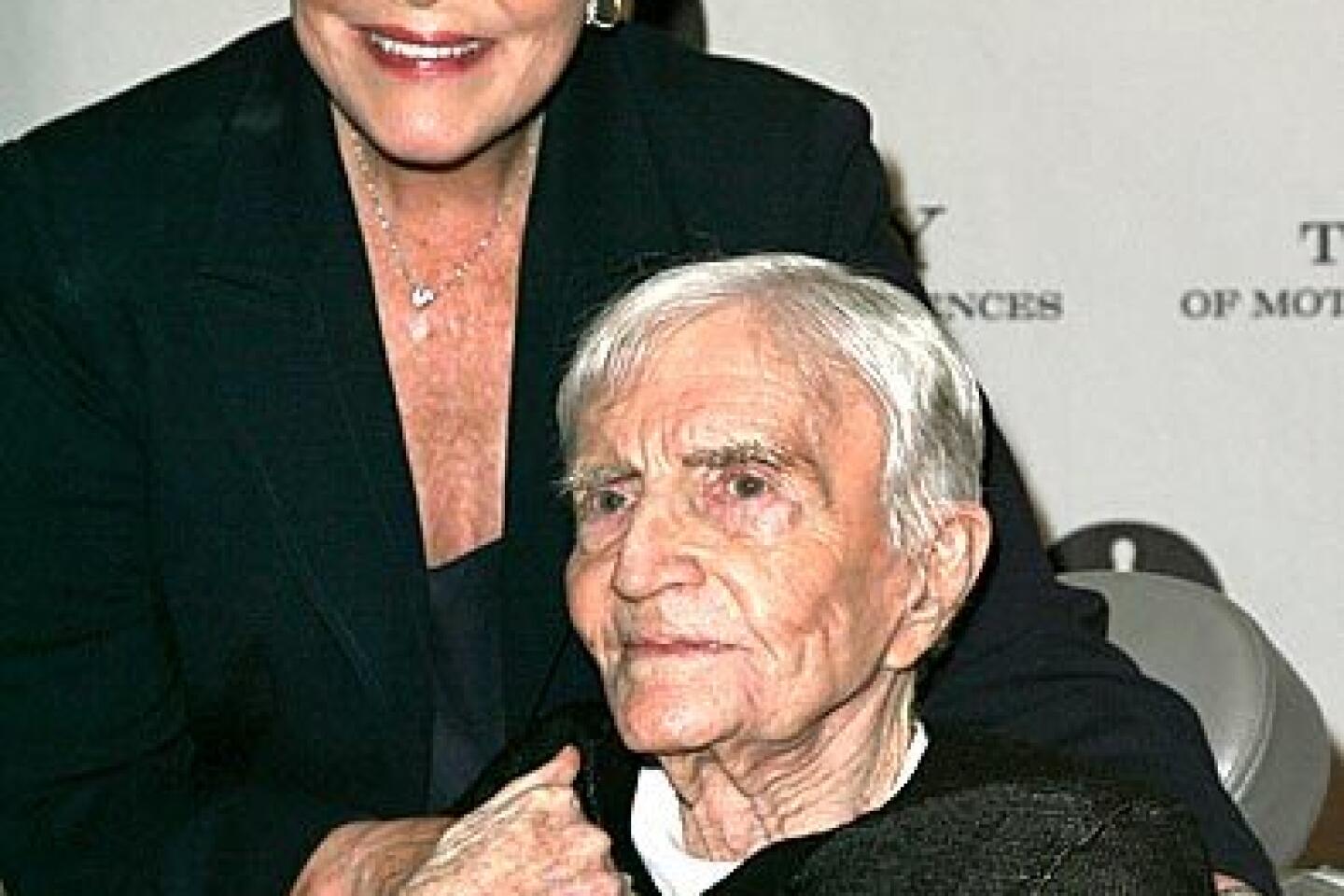

Edwards died of complications of pneumonia Wednesday evening at St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, said Gene Schwam, Edwards’ longtime publicist. His wife, Julie Andrews, and members of the immediate family were at his bedside.

“He was the most unique man I have ever known — and he was my mate,” Andrews, who collaborated with Edwards in the 1982 sex farce “Victor/Victoria” and other films, said in a statement Thursday. “He will be missed beyond words and will forever be in my heart.”

Film historian Jeanine Basinger, head of the film studies program at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., said Edwards is “at the absolute top of comedy filmmaking.”

“His movie comedies wed the American traditions of physical slapstick and sophisticated, witty dialogue,” Basinger told The Times in 2003. “But he also knows how to be funny cinematically through cutting, camera movement and framing. So he’s a consummate comedy film director.”

Edwards, who suffered from what he called “monstrous” depression throughout his life and at one point contemplated suicide, found release in making movies.

“My work has been one of the great therapies of my life,” he told GQ in 1989. “Being able to express myself and have it validated by laughter is the best of all possible worlds.”

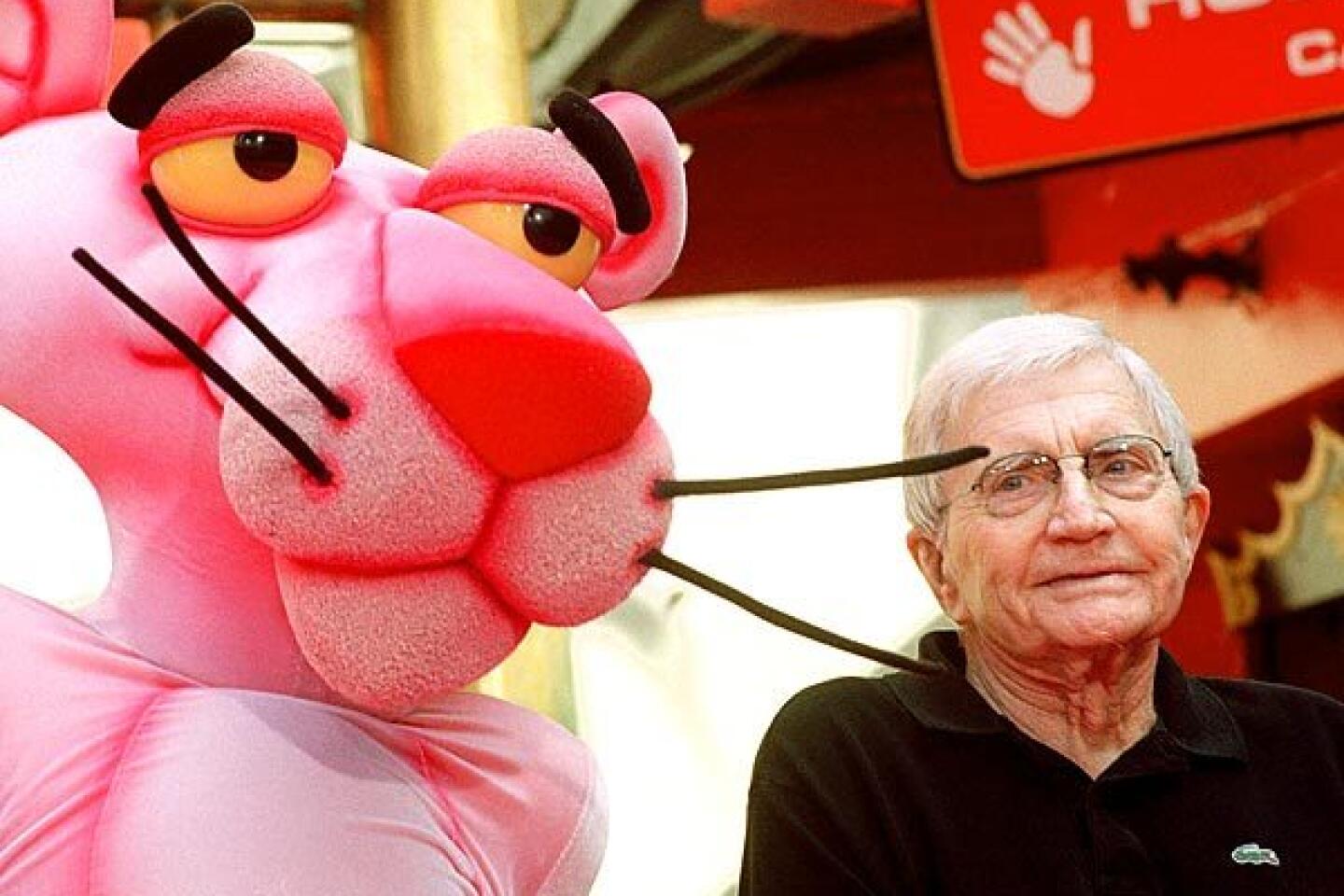

During a more than five-decade career, it was as co-writer and director of “The Pink Panther” and “A Shot in the Dark” (both released in 1964), starring Peter Sellers as the bumbling French police inspector, Clouseau, that Edwards earned his reputation for bringing slapstick and sight gags into the modern era.

Writer Maurice Richlin approached Edwards with the idea for a French inspector of police trying to catch a notorious jewel thief, and they collaborated on the script for “The Pink Panther.”

A reviewer for Variety called the film “intensely funny” and praised Sellers as Clouseau, saying he was “perfectly suited as a clumsy cop who can hardly move a foot without smashing a vase or open a door without hitting himself on the head.”

Sam Wasson, author of the 2009 book “A Splurch in the Kisser: The Movies of Blake Edwards,” said Edwards “has as many films that are respected as films that are reviled.”

“He hasn’t quite made it into the pantheon of great directors,” Wasson said. “People don’t really know where to place Blake Edwards because so much of his material is outwardly goofy, even though it’s sophisticated.”

And although Edwards had as many flops as hits, Wasson said, “I position him along the line of Hollywood’s greatest directors of comedy, beginning with [ Charlie] Chaplin and continuing with [ Ernst] Lubitsch, [ Preston] Sturges and [ Billy] Wilder.

“He was certainly the last great writer-director of mainstream Hollywood comedy.”

A onetime minor movie actor who began writing for films and radio in the late 1940s and a decade later created the TV series “Peter Gunn” and “Mr. Lucky,” Edwards launched his big-screen directing career in 1955.

He scored his first box-office hit with “Operation Petticoat,” a 1959 comedy about a World War II submarine crew starring Cary Grant and Tony Curtis. But a turning point in Edwards’ film career came in 1961 with “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

The sophisticated romantic comedy- drama based on the Truman Capote novella earned Audrey Hepburn an Academy Award nomination for best actress. Composer Henry Mancini also won an Oscar for his score, and he and Johnny Mercer won Oscars for their memorable song “Moon River.”

Edwards tackled darker fare in 1962 by directing the thriller “Experiment in Terror” and “Days of Wine and Roses,” a grim drama about a young couple ( Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick) battling alcoholism. But in the ‘60s he also directed such comedies as “The Great Race,” “What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?” and “The Party.”

As a director, Edwards had a career marked by his share of box-office failures, including “Darling Lili,” the notoriously over-budget 1970 musical World War I spy film that marked his first collaboration with Andrews, whom he had married in 1969.

Indeed, as much as he is known for the physical comedy in many of his movies and for exploring changing relationships between men and women throughout his career, Edwards is also known for fighting major battles over studio interference on his films — with Paramount’s Robert Evans over “Darling Lili” and with MGM’s James Aubrey over “Wild Rovers” (1971) and “The Carey Treatment” (1972).

His legendary disputes with studio chiefs inspired Edwards’ scathing 1981 Hollywood satire “S.O.B.”

“He’s always been admired and respected for the way in which he has fought for creative integrity and control for himself as a director,” Peter Lehman, director of the Center for Film, Media and Popular Culture at Arizona State University and coauthor of two books on Edwards’ films, told The Times in 2003.

Lehman said Edwards also went to bat for Mancini — with whom he had worked for decades beginning with the TV detective-drama “Peter Gunn” in 1958 — so that Mancini could retain the rights to his music. This set a precedent for other composers as well, Lehman said.

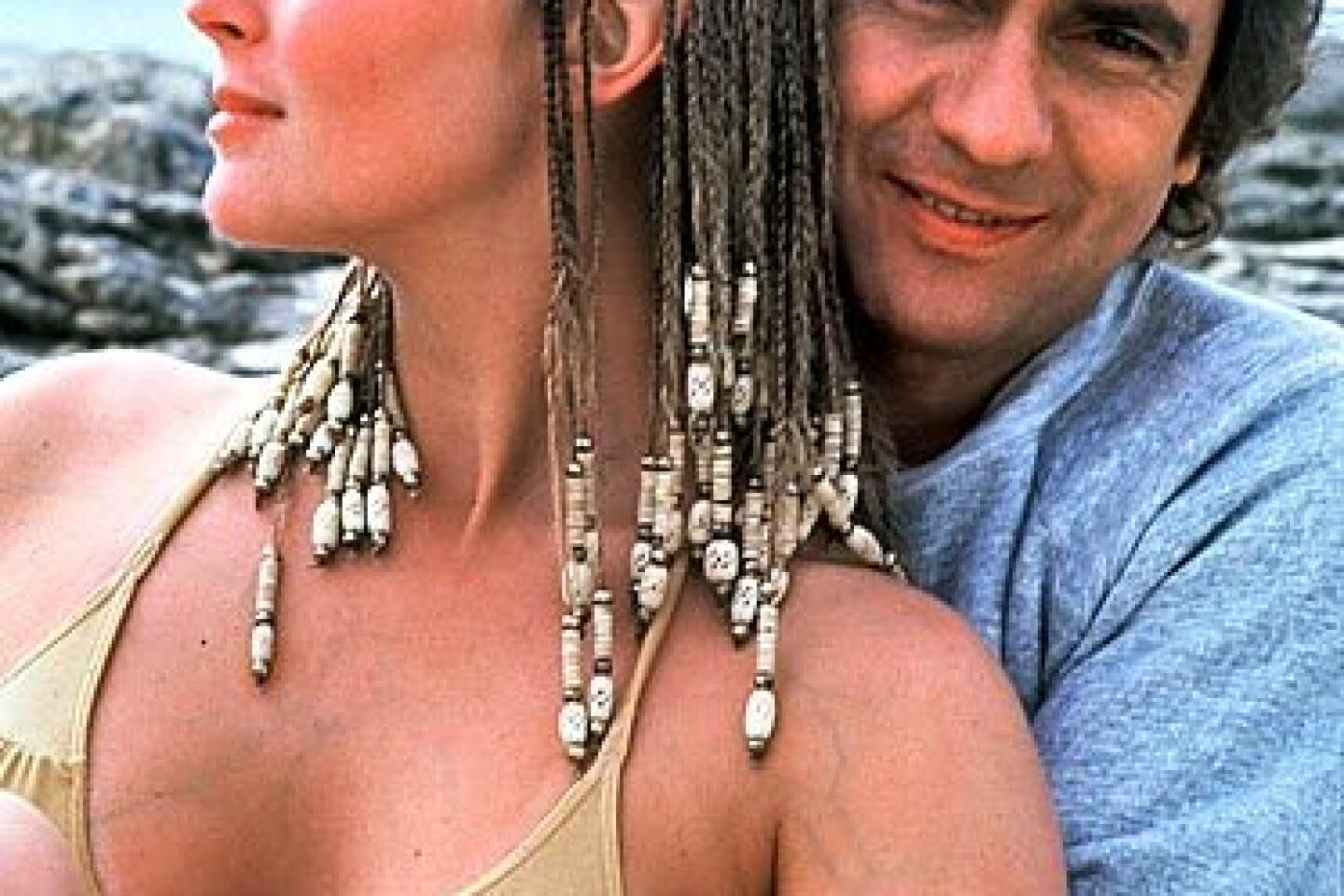

Basinger added that Edwards’ comedies such as “10” have “given us icons in our culture.”

“ Bo Derek with her corn rows coming out of the water is one of the great iconographic images of that decade,” Basinger said, adding that the 1979 film “put into the language the rating of a woman as a ’10.’ ”

Those who helped Edwards bring laughter to movie audiences praised his flair for comedy.

While making “10,” Derek told The Times on Thursday, she would “watch him, see this wicked, mischievous expression had come across his face and know that he had thought of something hilarious. It was a very nurturing environment, and I’ve never had that since.”

Burt Reynolds, who starred in Edwards’ “The Man Who Loved Women,” said in a statement Thursday that Edwards “was the most wonderful director that I ever worked with.”

“He had a brilliant sense of humor with a great eye and ear for comedy,” Reynolds said. “He will be greatly missed and is irreplaceable.”

Jack Lemmon, who appeared in three films directed by Edwards, once called him a “gutsy SOB” and a consummate “picture-maker.”

“Some people are wonderful directors,” Lemmon told GQ magazine in 1989, “but they’re not picture-makers. By that I mean they can direct an individual scene and it’ll be a real pearl. But when they string the scenes together, the effect isn’t worth much.

“With Blake, when he’s on his stick, you get a strand of pearls that’s just beautiful.”

Edwards was born William Blake Crump in Tulsa, Okla., on July 26, 1922. His biological father, Donald Crump, left Edwards’ mother before their son was born and she reportedly turned Blake over to an aunt and uncle to raise.

Around the time Edwards was 3, his mother remarried and he joined her in Hollywood, where her husband, Jack McEdward, the man Edwards always considered his father, was a studio production manager. McEdward was the son of film pioneer J. Gordon Edwards, who directed silent-screen star Theda Bara in the 1917 version of “Cleopatra.”

As an only child of parents who “didn’t know how” to love and who had trouble communicating not only with him but with each other, Edwards found escape at the movies.

“I naturally embraced the Laurel and Hardys, the Keatons and the great comics,” he told The Times in 1991. “I laughed and made my hours there happy. I could take a certain residual of that home with me.”

While growing up, Edwards also spent a lot of time on film sets and earned spending money working as an extra. After graduating from Beverly Hills High School, he landed a bit part in the 1942 film “Ten Gentlemen from West Point.” A couple dozen, mostly un-credited, minor film roles followed over the decade.

During World War II, Edwards served in the Coast Guard for 18 months. His last five months were spent at Long Beach Naval Hospital after he was seriously injured in a diving accident in a Beverly Hills swimming pool.

After the service, Edwards teamed with his friend John Champion to co-write and co-produce “Panhandle,” a 1948 western that Champion financed with money from his trust fund. The low-budget film starred Rod Cameron, and Edwards played the small part of a gunslinger.

“I was an actor and perhaps I perceive myself as continuing to be one, but I know I wasn’t that serious,” Edwards said in a 1993 interview for the Directors Guild of America’s publication DGA News. “I wasn’t that dedicated and I certainly wasn’t that successful. And success was important to me.”

After teaming with Champion, with whom he also wrote and produced the 1949 western “Stampede,” Edwards said he “suddenly realized that there was another world out there where I could be successful, not only by reputation and money. Writing really is the thing that turned me on.”

As a writer in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, Edwards created and wrote for the radio series “Richard Diamond, Private Detective,” starring Dick Powell; he also directed some of the episodes and wrote for “Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar” and “The Lineup.”

At Columbia Pictures from the early ‘50s to the early ‘60s, Edwards frequently worked as a writer with writer-director Richard Quine, including on the films “My Sister Eileen” (1955), “Operation Mad Ball” (1957) and “The Notorious Landlady” (1962). Edwards and Quine also worked together on “The Mickey Rooney Show: Hey, Mulligan,” a 1954-55 TV situation comedy.

The heavy workload of writing for films by day and for radio at night in the early ‘50s landed Edwards in therapy, but the self-analysis proved to be rewarding.

“For the first time, I began to see that I had more at stake in writing than just making money — that there was some sort of passion involved,” Edwards told GQ in 1989. “Also, I think I saw that for someone who had a need for control of one’s life, directing had great appeal.”

When Quine was promoted from Columbia’s B-film unit to larger-budget features, Edwards, who already had done some directing in television and radio, was given his first chance to direct a film: “Bring Your Smile Along,” a 1955 light musical comedy starring Frankie Laine and co-written by Edwards and Quine.

Over the next four decades, Edwards directed several dozen films, the majority of which he wrote or co-wrote and produced. Among them: “The Great Race,” “What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?” “The Party,” “Blind Date,” “Sunset,” “That’s Life!” and “The Man Who Loved Women.”

Depressed over his battles with Evans and Aubrey in the early 1970s — “I thought I was going to have a nervous breakdown,” he later told Time magazine — Edwards retreated to Switzerland for five years. Bolstered by his three hit “Pink Panther” sequels with Sellers, however, he returned to Hollywood to make “10.”

Edwards’ only Academy Award nomination was for the screenplay adaptation of “Victor/Victoria,” but in 2004 he received an honorary Oscar for “extraordinary distinction in lifetime achievement.”

He collaborated with Andrews on seven movies, a short-lived TV series and a Broadway musical adaptation of “Victor/Victoria.”

In addition to his wife, Edwards is survived by his daughter and son from his first marriage, Jennifer and Geoffrey; two adopted Vietnamese daughters, Amy and Joanna; a stepdaughter, Emma; seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

A public memorial is planned for January.

Times staff writer Valerie J. Nelson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.