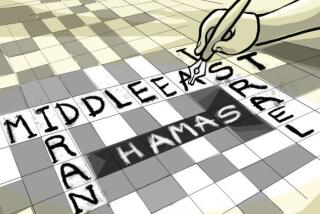

Cairo is not Tehran

Doomsayers are already warning that we’re seeing a remake of Iran’s Islamic revolution in Cairo. And on the surface, there are certainly parallels.

Then, as now, a popular uprising caused the United States to nudge a longtime ally, and autocratic leader, toward the exit. And then, as now, the White House searched for a way to hold the country together.

In Iran’s 1979 version, Islamic radicals were waiting in the wings and installed a virulently anti-American religious dictatorship.

Is that what will happen in Egypt in 2011? And is President Obama another Jimmy Carter, fecklessly abandoning a loyal ally despite mortal dangers ahead?

Not likely. Egypt isn’t Iran; Obama isn’t Carter. In some respects, Obama has steered a very different course from Carter’s a generation ago. Carter stood by Iran’s doomed shah for months before scrambling to look for alternatives; Obama bluntly told Mubarak his time was up after only a week of demonstrations in Tahrir Square. And unlike Carter, Obama has a strategy; he’s placing his bets on Egypt’s military command to oversee a peaceful change of power.

For all these reasons, Obama has a far better chance of seeing a benign outcome in Cairo than Carter did in Tehran. Still, no matter how well the Obama administration plays its hand, there are plenty of ways the situation in Egypt can go bad. And if it does, the president almost certainly will be blamed.

Having covered the Iranian revolution in 1979, I see more differences than similarities between Egypt today and Iran then. Egypt’s revolution has many leaders, not a domineering religious figure like Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Its military hasn’t gunned down demonstrators in the streets, so its armed forces still enjoy popular respect. Perhaps most important, its military commanders appear to be embracing the mission of managing peaceful change in the political system, unlike the shah’s generals, who were divided and uncertain.

“These revolutionaries in Egypt don’t remind me very much of Iran in 1979,” said Abbas Milani, who marched in Tehran a generation ago. (Now a scholar at Stanford University, he just published a biography of the shah.) “They seem more like the Green Revolution in Tehran in 2009: they are peaceful, they have no cohesive leadership, and they have no program besides getting the dictator out.”

Obama’s relatively quick decision to encourage Mubarak to leave power is in sharp contrast with Carter’s actions in 1979. “That’s the big difference,” said Gary Sick, who was Carter’s top NSC expert on Iran at the time of the revolution. “In the case of the shah, we spent a lot of time trying to help him save himself.”

And the Obama administration has sent clear messages to Cairo, without any apparent internal divisions; the Carter administration was divided, and sent conflicting signals to Tehran. “Even the shah wasn’t sure what the U.S. position was,” Milani noted.

Now, Sick says, the important thing will be for the Obama administration to keep up the pressure on Egyptian Vice President Omar Suleiman and other military leaders to bring about real change, without allowing the revolution to spin out of control — no easy task.

“The longer this drags out, the more likely that radical groups will rise up and assert themselves,” he said.

That’s one reason the administration has been so insistent on warning the military against firing on unarmed demonstrators. If the military commits a massacre, the armed forces could fracture, depriving the United States of its main avenue of influence.

It’s clear, as Obama administration officials have noted, that the United States can’t control the outcome in Egypt.

“What the administration would like is an orderly transition; they’re not going to get that,” said Martin Indyk of the Brookings Institution, a former assistant secretary of State. So now the administration is aiming merely for a peaceful transition, he said. “Beyond that, there’s not a lot we can do about where this goes, except to hope and pray that it comes out OK.”

The best-case outcome looks like a year of instability in which Egypt evolves toward something like Turkey: a democracy with powerful Islamic parties kept in check by a powerful military. Egypt is likely to remain a U.S. ally, but a more prickly one.

The worst-case outcome? Depending on the power and militancy of its Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt could yet move in the direction of religious autocracy, although most experts consider that unlikely. In any case, it won’t be a carbon copy of Iran; Egypt’s Sunni form of Islam is very different from Iran’s Shiite sect.

This wasn’t the issue on which Obama wanted to spend his days and nights this spring. The plan was to spend the next few weeks selling his proposals for rejuvenating the U.S. economy and creating jobs, defending his budget and jousting with Republicans over federal budget cuts.

Instead, he’s perilously close to a no-win situation. He’s presided over swift and orderly decisions on a strategy in Egypt, but the story could still come out wrong.

Even the best-case scenario comes with plenty of discomfort. A cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy has crumbled, and Obama will collect some of the blame.

He’s no Jimmy Carter. But thanks to the hazards of the Middle East, there may be days when he feels almost as beleaguered.

doyle.mcmanus@latimes.com

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.