Drawing the lines

One of the most tiresome side effects of California’s initiative process is that few political battles in this state are ever won for good. The losers always have another chance to persuade voters to reconsider their earlier decisions. That’s at work in one of November’s least persuasive ballot measures, Proposition 27, which would roll back a vote of just two years ago. What’s especially strange about this appeal to second thoughts is that the measure Proposition 27 seeks to undo hasn’t even done anything yet.

In 2008, California voters did away with the system under which members of the Assembly and state Senate draw the boundaries of their own districts. It was a close election — the same idea had failed before — but voters ultimately concluded that they did not trust the members of the Legislature to supervise this inherently self-serving process. Instead, the voters approved creation of an independent, nonpartisan citizens commission to take on the business of crafting California’s legislative districts. Advocates, including Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and this page, saw it as a promising way to begin chipping away at some of Sacramento’s calcification.

The commission is still under construction, and it has not yet begun to work. That’s because the next redistricting cannot commence until the state’s population is tallied in the 2010 census. But the losers of the 2008 vote are already attempting to eliminate the commission and return the line-drawing to the Legislature. They’re the ones behind Proposition 27.

Proponents of the proposition smugly titled it the Financial Accountability in Redistricting Act, and they argue that it will save money — that California cannot, in this hour of fiscal crisis, afford the 14-member commission and the staff required to carry out its duties. That’s fraudulent, and they know it. California’s crisis is real, but the citizens commission is an antidote, not a contributor. The real culprit is Sacramento’s self-sustaining, incumbent-protecting politics, a system in which legislators bicker about and deadlock on almost everything, with one glaring exception: Democrats prosper by drawing themselves solidly Democratic seats, and Republicans benefit equally by lines drawn to protect their elected officials. So both sides have declared a redistricting truce, leaving out only the people of the state and their interest in holding leaders accountable.

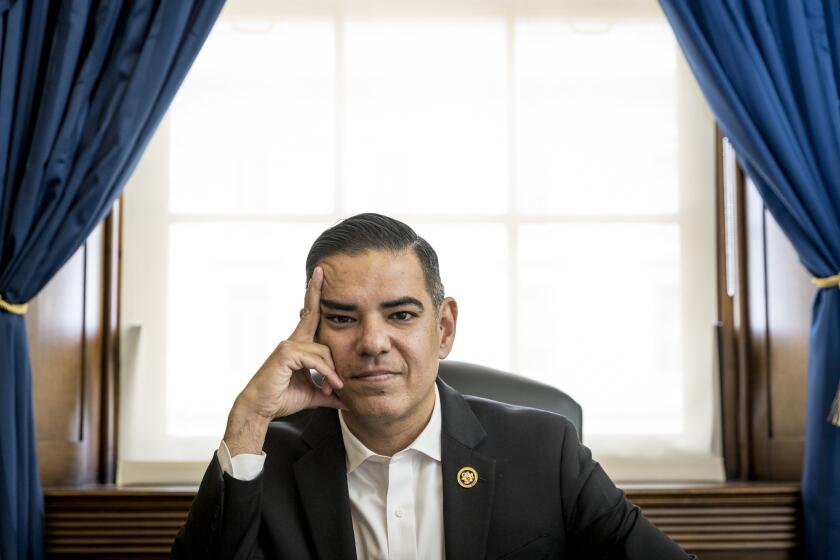

That’s the reason that big money — members of Congress, current and former leaders of the Legislature and their prosperous, connected friends — is supporting Proposition 27. Speaker John Perez (D-Los Angeles), who would supervise redistricting in the Assembly if it is put back under legislative jurisdiction, has donated $10,000; so has his predecessor, Assemblywoman Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles). Billionaire Haim Saban, a reliable friend of Democratic officeholders, has chipped in at least $2 million. That’s no surprise. Incumbents in this state are overwhelmingly Democrats, so money for the measure has overwhelmingly come from Democratic leaders, unions and liberals. Republicans, thinking they might fare better with a nonpartisan commission than with their Democratic counterparts, are largely taking a pass. But that should be of no comfort to liberals or union members. This effort is not ideological; it is self-interested. Proposition 27 protects a politics of privilege and incumbency, which is bad for everyone but those who hold office.

Proposition 20, meanwhile, is an anti-companion bill of sorts. Whereas Proposition 27 would eliminate the citizens commission, Proposition 20 would expand its authority, giving it the power to draw not just legislative lines but congressional ones as well. The argument for citizen oversight of the latter is one notch less compelling: Members of Congress do not draw the lines for their own seats, so the opportunity for self-dealing is less immediate.

But the arguments in favor of removing redistricting from elected state leaders carry over into federal offices as well. Rare is the Sacramento politician who doesn’t imagine himself or herself holding forth in the U.S. Capitol. Especially in this unfortunate era of term limits, Assembly members and state senators eye the next office soon after landing, and congressional seats are all the more inviting because they come with the potential for unlimited tenure. The ambitious legislator can use the power of redistricting to craft a seat to run for a few years down the road — the liberal Democrat from San Francisco or Los Angeles who wants a seat in Congress can draw lines that suit his demographics; the same goes for the conservative out of San Diego County or the Central Valley. Moreover, the up-and-coming politician knows better than to antagonize members of Congress, so they work together, at the expense of the public.

Proposition 20 acknowledges that reality. It deserves approval.

The proponents of Proposition 27 are the opponents of Proposition 20, and they advance two curious objections: that it wouldn’t accomplish anything, and that if it does accomplish anything, it will be to California’s detriment. Setting aside the inconsistency, one point is fair: Approving Proposition 20 won’t change California tomorrow. Political reform — including the creation of the citizens redistricting commission and the recently approved “open primary,” which will allow Californians to vote across party lines in primaries — will not yield instant results. It may, however, gradually break down some of the impediments to efficiency and deal-making that have thwarted Sacramento in recent years and that have wreaked havoc in Washington as well.

Today, California’s elected leaders represent districts handcrafted to make it easy for them to avoid challenges from the other party. With few exceptions, lines are drawn so that their constituents either are overwhelmingly Democratic or overwhelmingly Republican, and the strategy for retaining office is to avoid any move that would offend the party’s base. That discourages moderation and compromise, and that, in turn, has led to gridlock of epic proportions.

By creating a citizens redistricting commission, Californians took one step away from making that gridlock a permanent feature of our politics. By approving the open primary, Californians took another. Neither of those reforms has yet been tested in an election, so they have yet to alter the contours of our politics, but they deserve a chance to work, and they have the potential to make a difference. If not, why would so many of this state’s incumbents spend so much time fighting them?

The Times’ endorsements in the Nov. 2 election are collected at latimes.com/opinion.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.