The Supreme Court rules out some -- but not all -- gene patents

This post has been corrected, as noted below.

When it took up the issue of patents on human genes, the Supreme Court seemed torn by two conflicting interests: the long-standing principle that products of nature can’t be patented, and the commercial reality that companies won’t invest in crucial but risky R&D; efforts unless they have a chance to patent what they develop.

The justices tried to serve both ends Thursday. Their unanimous ruling in Association for Molecular Pathology rejected the patents that Myriad Genetics had on two gene sequences isolated from humans, but upheld the ones over synthesized versions of those sequences that differ from the ones found in the body -- a concession that’s important to the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. The court also made clear that it wasn’t closing off other sorts of patents that could be sought by companies that isolate human genes.

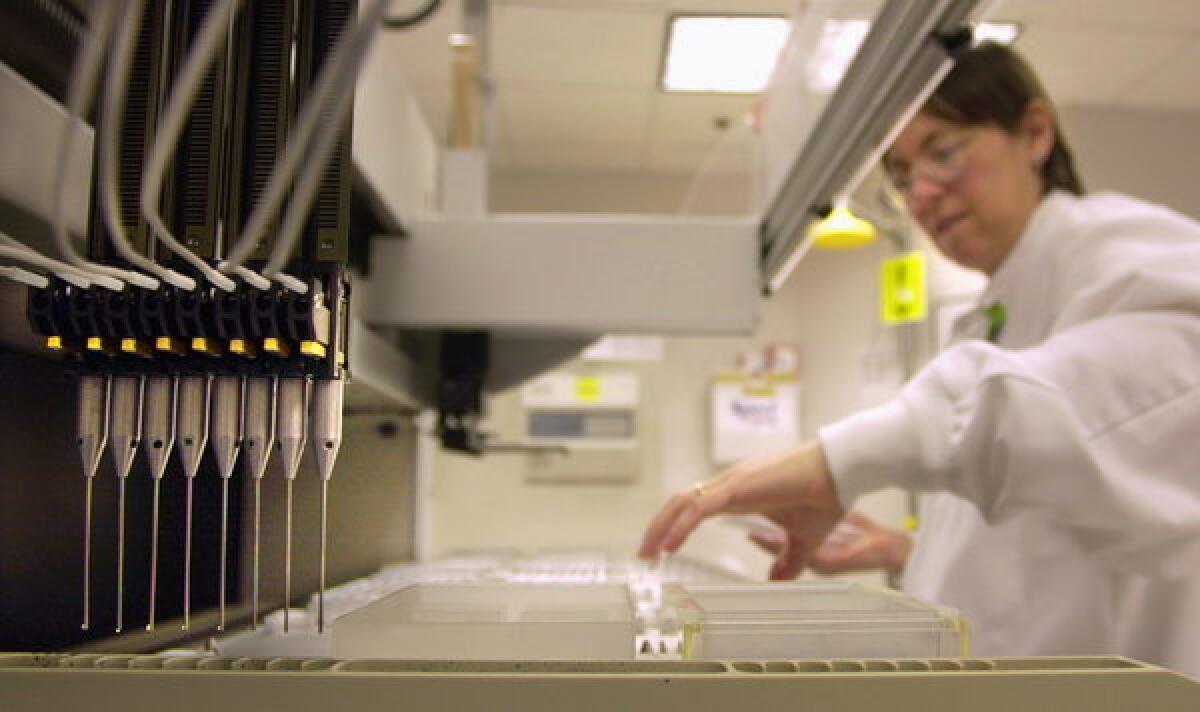

The patented sequences, BRCA1 and BRCA2, are genes that suppress tumors. Certain mutations of those genes are so strongly associated with breast and ovarian cancer, some women (such as actress Angelina Jolie) with those mutations choose to have healthy breasts and ovaries removed as a preventive measure. But Myriad’s patents over those sequences effectively gave the company control over which labs could perform the tests, how much the tests costs, and what variations and mutations the tests sought to identify.

The plaintiffs in the case, which included academics, doctors and individual women, sought to break Myriad’s hold over research and testing related to the genes. They claimed victory Thursday, saying the court’s ruling will enable more doctors and labs conducting tests. That competition, in turn, will lead to higher quality results and lower prices, they said.

They also contended that labs will be able to create and conduct more types of tests, such as specialized tests for specific populations, making it easier to find women who are at risk. The same should be true for other diagnostic tests that have been monopolized through gene patents, they said.

Plaintiff Harry Ostrer, a professor of Pediatrics, Pathology and Genetics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and Montefiore, said there are about 4,000 patents over isolated human genes. According to Ostrer and Roger Klein of the Association for Molecular Pathology, the tests affected by gene patents include those for spinal muscular atrophy, a deadly congenital heart problem known as long QT syndrome, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Perhaps more important, some researchers say, the ruling should encourage more work on issues connected to BRCA1, BRCA2 and other gene sequences covered by patents because it reduces the fear of legal liability.

As definitive as the ruling seems, analysts say it won’t necessarily have a major impact on Myriad or other companies holding patents to genetic tests. By allowing patents on cDNA, among other claims related to human gene sequences, the justices left intact a potential thicket of patents surrounding a genetic test.

That’s certainly Myriad’s view; the company argued that the ruling still leaves it with “strong intellectual property protection for our BRACAnalysis test moving forward.”

Said James F. Mullen III, an attorney and patent specialist at Morrison Foerster in San Diego, “It’s not like this decision is going to cut the head off gene claims all together.” In fact, he said, companies will probably still be able to corner at least some aspect of the testing market. “Bottom line, [the] Myriad [ruling] did not close the door on diagnostic claims,” Mullen said.

Michael J. Shuster, an attorney at Fenwick & West in San Francisco who specializes in life sciences, agreed that “there’s a lot of space left by the decision” to obtain patents over diagnostic and therapeutic inventions, even ones that involved such natural substances as proteins. But he worried that the ruling might limit patents over molecules that are identical to ones produced biologically -- an emerging field in drug development.

“That’s where the law of unintended consequences comes into play,” Shuster said. Companies may be able to avoid that trap by subtly altering the molecules they isolate, he said, but that would be “a stupid, ridiculous hurdle that the court has created, perhaps unknowingly.”

Sandra Park, an ACLU attorney who helped challenge Myriad’s patents, said she didn’t think that was a likely development. There’s a difference between merely isolating something that exists in nature, Park said, and extracting, purifying and concentrating it so that it can be put to a new use.

[For the record, 3:44 p.m. June 13: The original version of this post misspelled the name of Roger Klein of the Association for Molecular Pathology, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit.]

ALSO:

A smarter way to deal with China

McManus: Head-in-the-sand Congress

Belviq, the new miracle diet drug? Fat chance.

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.