Capitalizing on Che Guevara’s image

IF THIS were a photo session, you couldn’t have asked for more. The model, long-haired with steely gaze and wispy guerrillero beard. Jacket zipped to the chin. Collar up and hair uncombed. Jaw set in anger. Beret at a perfect, rakish tilt. There’s tension even in his pose: his shoulders turning one way, his face another. And those eyes, mournful but defiant, staring up and to the right as if at some distant vision of the future, or a giant, slow-approaching foe.

Snapped in March 1960, Alberto Korda’s iconic image of Ernesto “Che” Guevara is possibly -- who’s counting? -- the most-reproduced photograph in the world. Some version of it has been painted, printed, digitized, embroidered, tattooed, silk-screened, sculpted or sketched on nearly every surface imaginable. Brick and mortar city walls. Poster board waved high above a crowd. Gisele Bündchen’s bikini.

And though he never went away -- except in the strictly mortal sense -- Che is suddenly everywhere again. In October, an Iranian student militia organized a “Che Like Chamran” conference, attempting to enlist the martyred Marxist in the Islamic revolution. (They made the mistake of inviting his daughter, who pointed out that her dad did not believe in God.) Hollywood is at it as well: Steven Soderbergh’s long-anticipated, two-part Che biopic (“The Argentine” and “Guerrilla”) premiered May 21 at Cannes, with Benicio Del Toro playing the legendary Argentine-doctor-cum-internationalist-revolutionary. And “Chevolution,” Trisha Ziff and Luis Lopez’s documentary on the mass dissemination of the Korda image, is now making the film festival rounds.

Images have a way of shedding context, shaking off history. But just so you know: Korda snapped the shot in the idealistic first blush of the Cuban Revolution, before the Bay of Pigs invasion, before Fidel Castro aligned himself with the Soviet Union. One day earlier, an explosion in Havana harbor ripped through a Belgian cargo ship bearing munitions for the nascent regime. Castro blamed the CIA. At the memorial service for the many dozens killed, Korda clicked the shutter and caught Guevara on the podium, angry but determined, staring fearlessly off into the yonder.

The image spread mysteriously, apparently with a will of its own. Revolución, the Cuban newspaper, used it to announce a conference on industrialization at which Dr. Ernesto Guevara, then minister of industry, planned to lecture. Korda gave a print to the Italian leftist publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who distributed it as a poster when he got home. Around the same time, Paris Match somehow got a copy and published it beside a July 1967 article asking “Che Guevara -- Where Is He?” And on the facing page, there is a photo of a crowd gathered in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución. Waldo-like, Korda’s portrait is there already, printed on a placard carried by the crowd.

The portrait would outlive its subject. Immediately after Che’s death in October 1967 (in the highlands of Bolivia, where he is now worshiped as a saint), the image multiplied. Marchers carried it through the streets of Milan, Italy, to protest his execution. May ’68 swung fast around the corner. There he was in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and in Prague, in Mexico City, Paris, Washington, Vietnam.

Transformation

THE IMAGE quickly mutated. It was not just the age of protest after all, but of Pop Art and the sly Warholian conflation of culture, celebrity and commerce. Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick flattened out the shading into a bold, T-shirt-friendly graphic in black, white and red. He wanted the image “to breed like rabbits,” and it did.

But the shadows and complexities of Che’s life and legacy disappeared as well. The man became a logo. As Ivan de la Nuez, a Barcelona, Spain, museum director quoted in Ziff and Lopez’s film puts it, “Capitalism devours everything . . . even its worst enemies.” Che has proved an abundant meal. His image has sold Converse sneakers and Smirnoff vodka. “Viva Gorditas,” barks the Taco Bell Chihuahua, donning a Che beret.

“You think it’s funny,” the Clash once sang, “turning rebellion into money.” Maybe not funny but quite a trick: There’s Che beer, Che cola, Che cigarettes, the inevitable Cherry Guevara ice cream. Online at thechestore.com, you’ll find Che’s face on hoodies, beanies, berets, backpacks, bandannas, belt buckles, wallets, wall clocks, Zippo lighters, pocket flasks and of course, T-shirts. La La Ling in Los Feliz sells Che onesies for the wee ‘uns. I bought my 3-year-old niece a plush Che doll one Christmas. She abandoned him for Dora the Explorer.

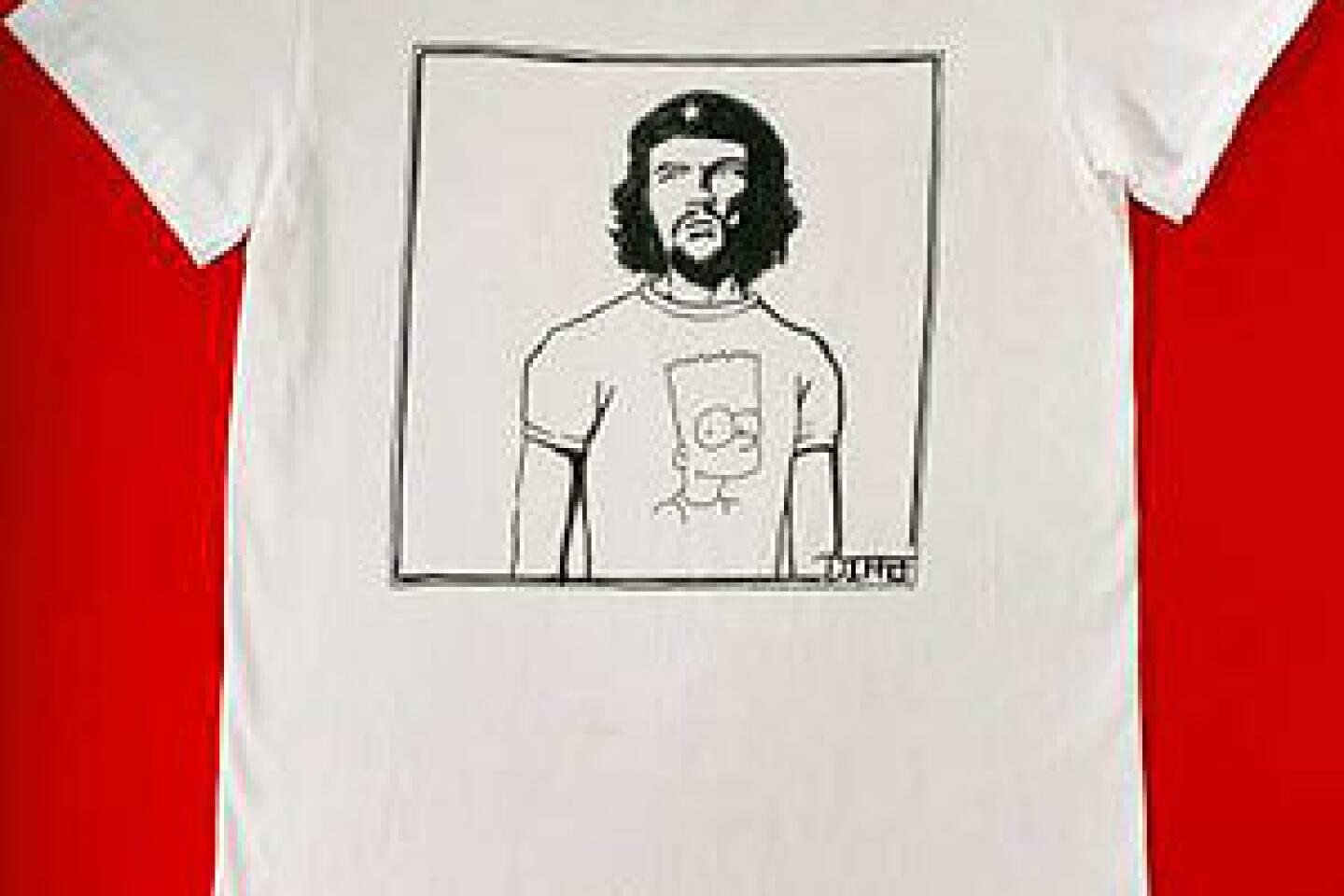

Online I found a T-shirt for sale depicting Homer Simpson sporting an arm tattoo of Che, and then there is the famous New Yorker cartoon featuring Che wearing a T-shirt depicting Bart Simpson (and now a T-shirt itself). What could it possibly mean? Only that the Che tee has itself become a symbol, shorthand for posture drained of ideology, rebelliousness as fashion statement. Other notable wearers of Che tees: Kyle from “South Park,” Prince Harry, Jay-Z, who rapped on “The Black Album,” “I’m like Che Guevara with bling on,” which is about as likely as Che the jihadi, but never mind.

The “Chevolution” soundtrack features a song by the Australian punk band the Clap called “Che Guevara T-Shirt Wearer.” (That rhymes in Australia.) “You’re a Che Guevara T-shirt wearer,” the chorus goes, “and you have no idea who he is.” Ziff and Lopez interviewed a young Republican on the UCLA campus, who thought Che was a musician, and a bicyclist in Venice Beach, who identified the face on his T-shirt as “the guy who invented those mojitos.”

But despite that, and despite the selling and sampling and all the multilayered appropriations, Ziff maintains that Che’s image still means something, even if it’s something as generic as protest, nonconformity, a wish for change. “It’s diluted,” Ziff says, but “I don’t think it’s ever lost its edge.”

To a degree, she’s right. Rebels and activists the world over still take inspiration from Guevara. But the image has lost something; Che’s face on a poster in 1968 isn’t quite the same thing as it is on a mousepad 40 years later. Perhaps it is precisely that loss -- the shedding of Che’s radicalism and ideological rigor -- that renders him so supremely marketable today. Things are not going well these days. Kids don’t want revolution so much as, um, something different.

So it shouldn’t be a surprise that L.A. artist Shepard Fairey, in his design for a Sen. Barack Obama poster, looked to Korda’s Che. Fairey’s Obama is not wearing a beret, and he’s looking left instead of right, but his face tilts at the same angle as Che’s. His jaw is set with the same willfulness and strength, and he too is gazing recognizably upward into the future (hasta la victoria siempre . . . ). Obama’s eyes, though, are filled not with righteous anger but with vague and lofty hope.

Che means change, if nothing else -- and not necessarily Marxist or anti-imperialist or radical at all. Today, his face can mean almost anything. He can even symbolize dissatisfaction with the regime he helped establish. In Cuba last spring, I met a young rapper from the slums of central Havana who was thoroughly disenchanted with Castro’s revolution. I asked him whom he would prefer as president, Fidel or Raúl Castro. He laughed and shook his head. “I’d prefer Che,” he said.