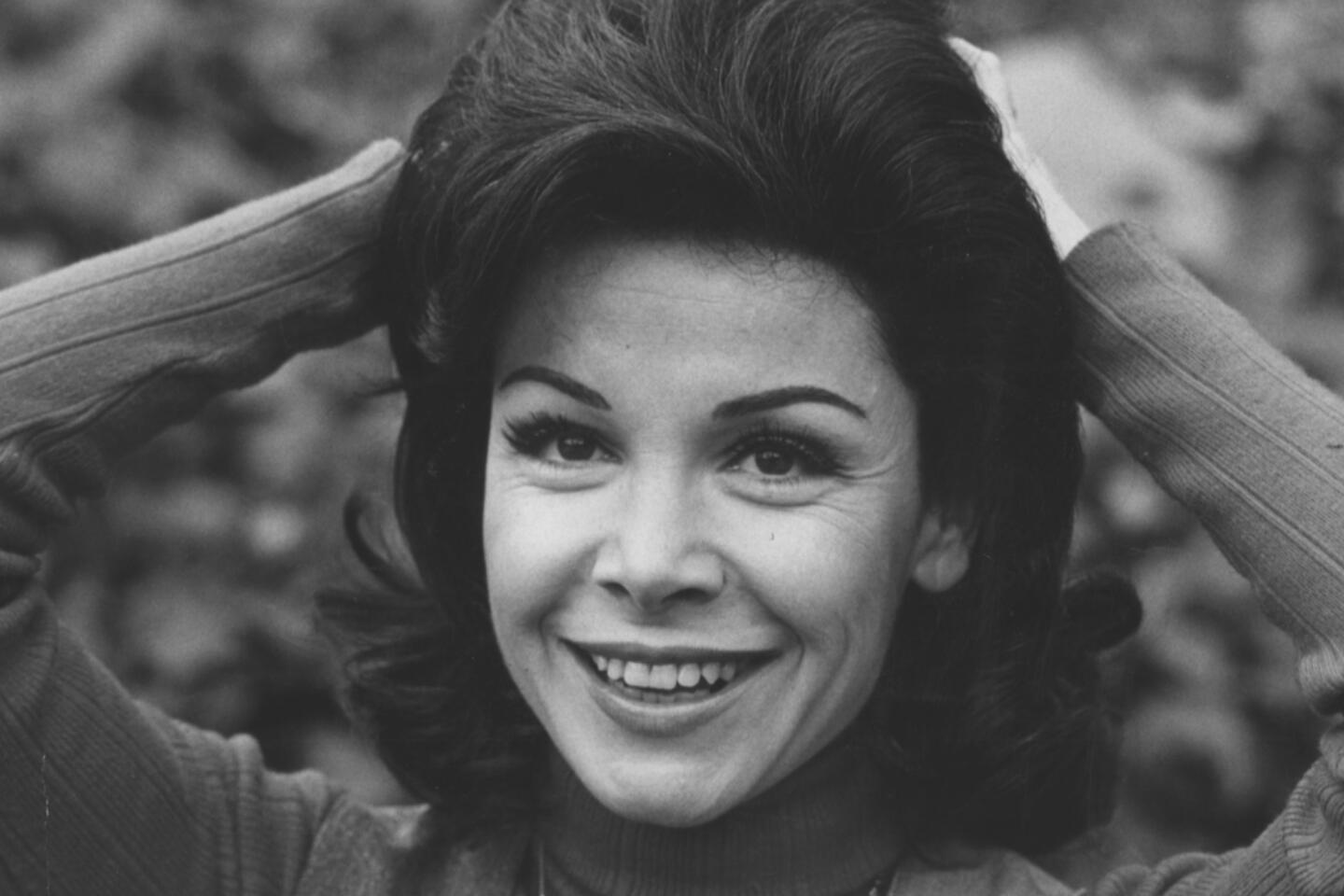

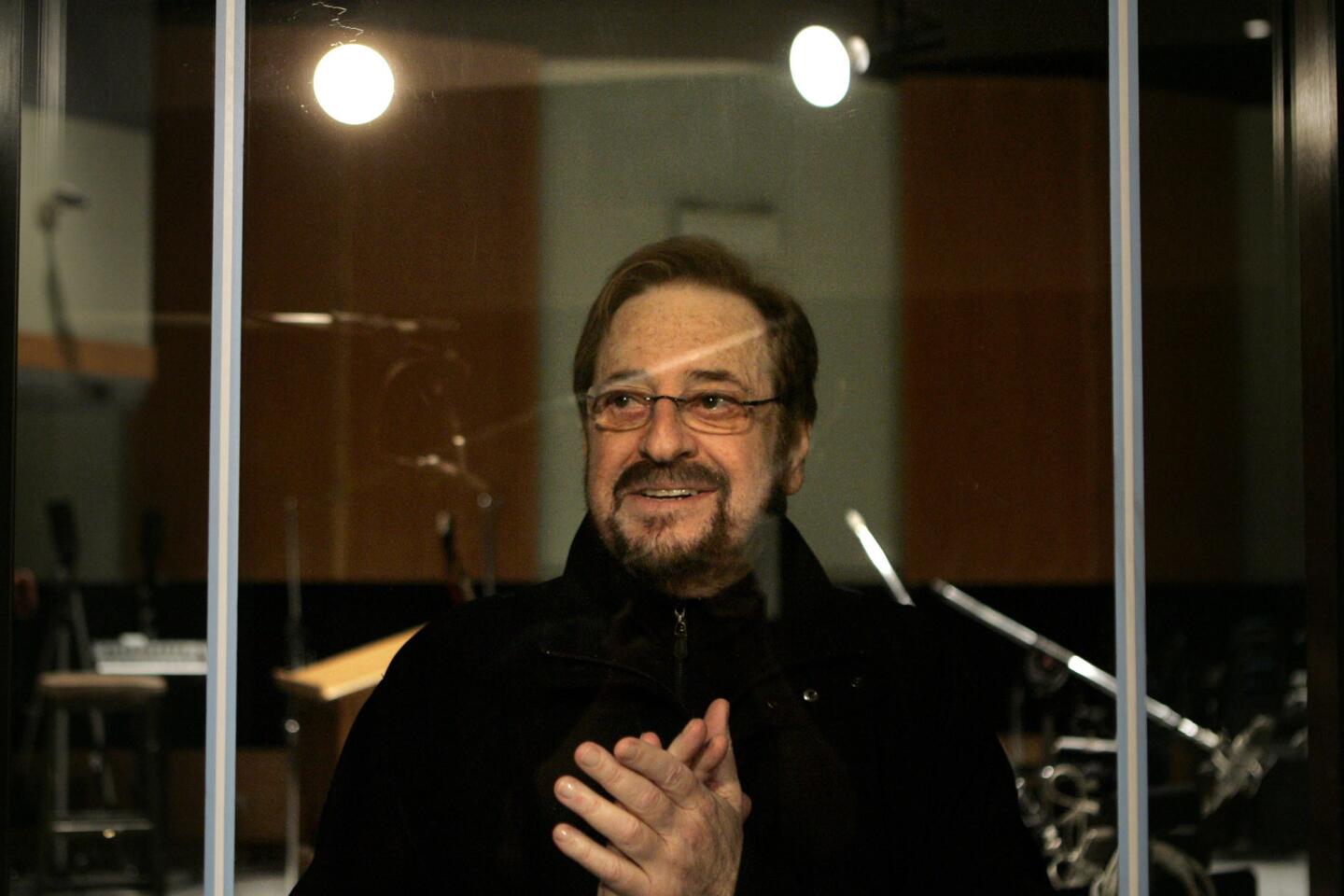

Dr. Jacquelin Perry dies at 94; polio specialist

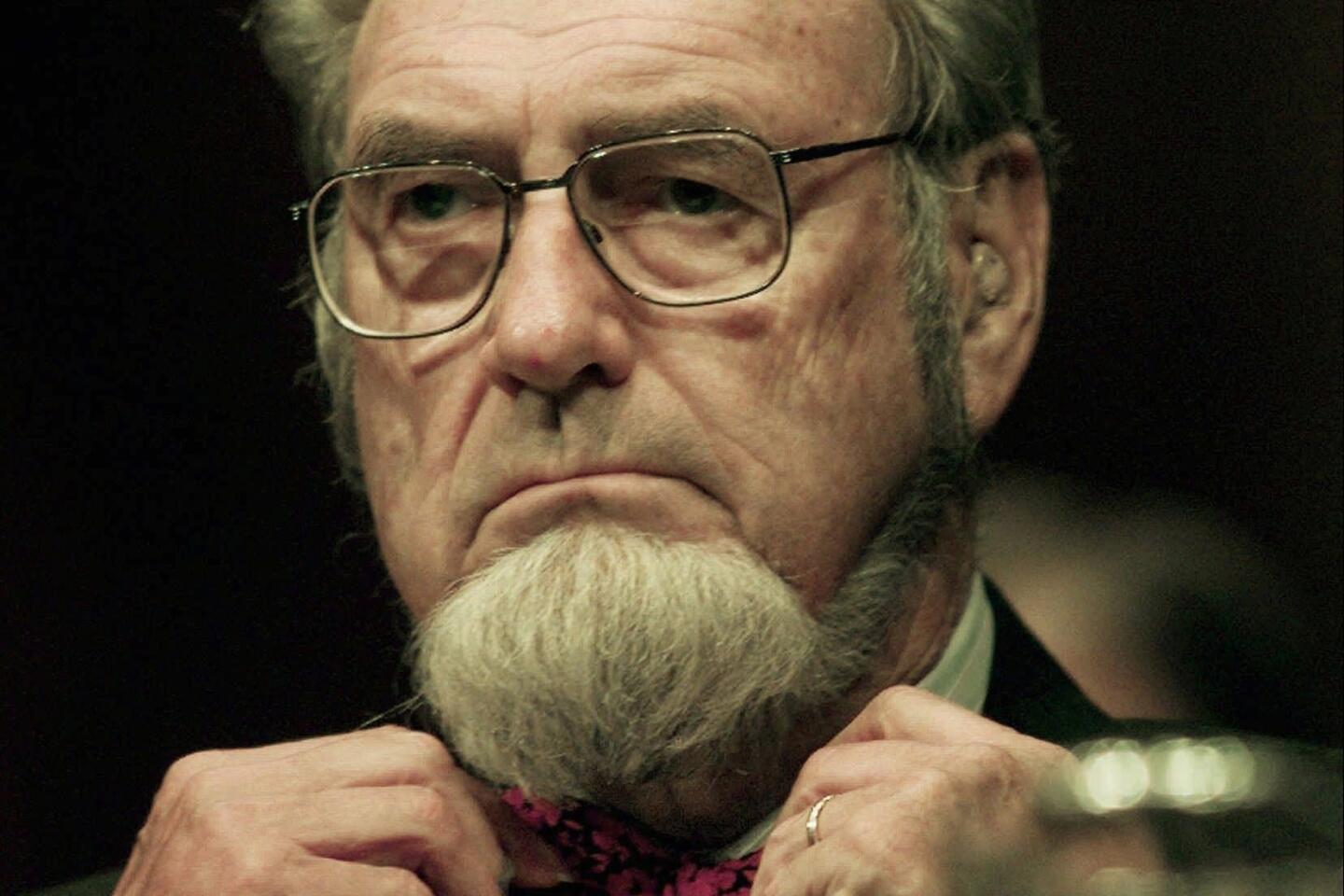

The country was in the grip of a polio epidemic in the 1950s when orthopedic surgeon Dr. Jacquelin Perry began performing spinal surgeries in Downey that helped paralyzed survivors of the disease regain mobility.

When some of the same patients returned to her 40 years later seeking help for pain and muscle weakness wrought by the aftereffects of polio, Perry remained true to form.

She blazed a trail, transforming herself into the leading authority on post-polio syndrome. She was also known for her pioneering analysis of the human gait, publishing a definitive textbook on the subject in her 70s.

Perry, who had Parkinson’s disease but was still practicing as of last week, died Monday at her home in Downey. She was 94.

Her death was announced by Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, with which she had been affiliated since 1955.

“She was a giant, a revered figure in her field,” said Greg Waskul, executive director of the center’s foundation. “Dr. Perry was so creative and innovative. Most of the great doctors have one specialty, but she came up with many new theories and exercises to keep people moving.”

During World War II, Perry had served as a physical therapist in the Army, treating polio patients in Hot Springs, Ark. But she yearned to “make my own decisions,” she later said, and decided to study medicine at UC San Francisco.

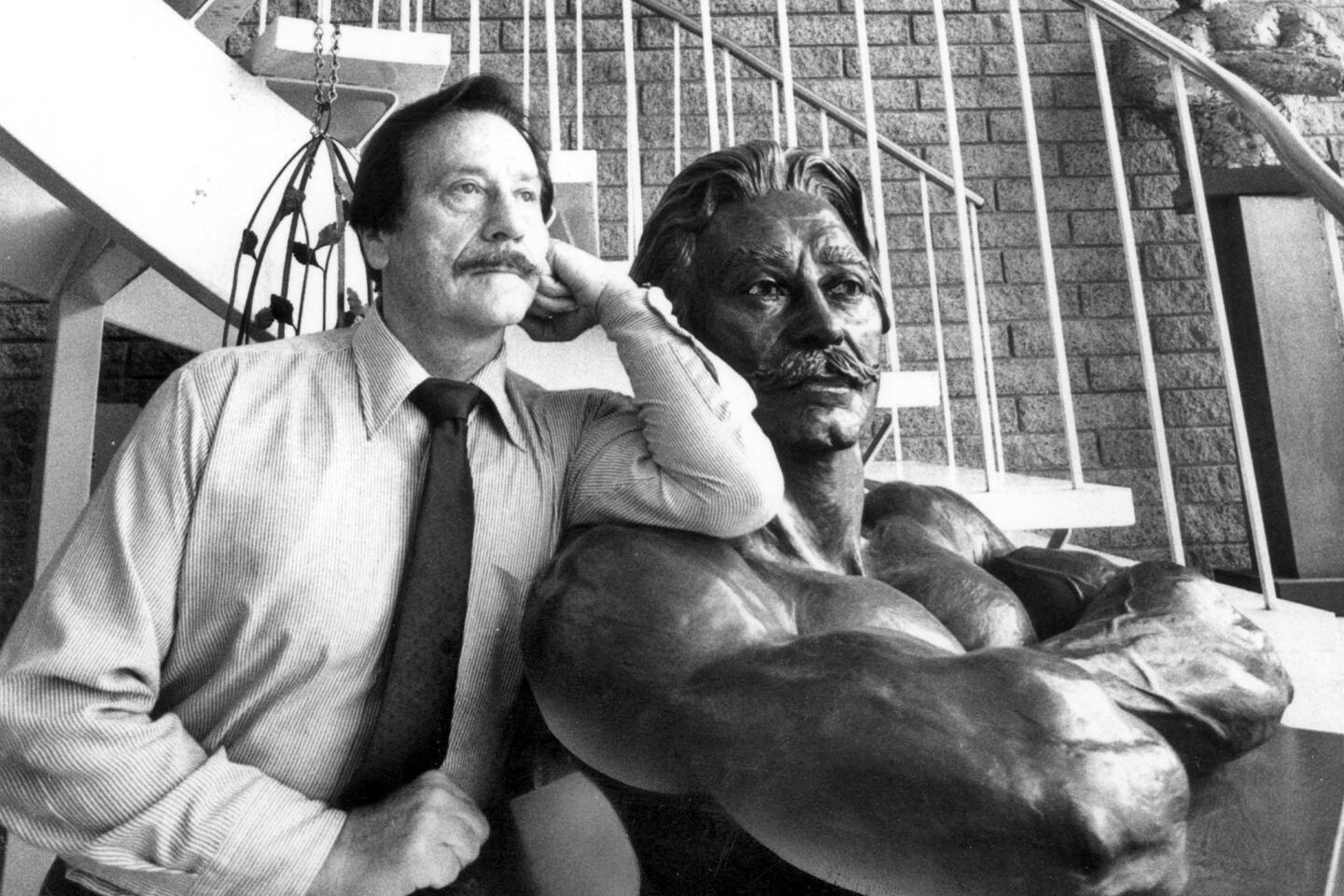

After joining Rancho Los Amigos, Perry collaborated with Dr. Vernon Nickel on polio cases. For spinal surgery patients, the pair developed the halo, a metal ring still in use today that is screwed into the skull, immobilizing the spine and neck.

When The Times honored her as the 1959 Woman of the Year in science, Perry pointed out that “most doctors go into medicine to save lives. I’m more interested in getting handicapped persons functioning again.”

After a brain artery blockage forced Perry to stop operating, she founded Rancho’s Pathokinesiology Laboratory in 1968 to analyze the biomechanics of walking. She served as chief of the department until 1996 and continued to consult in semi-retirement.

“Dr. Perry was a visionary pioneer in the field of rehabilitation sciences and gait analysis,” said Judith M. Burnfield, director of the Institute for Rehabilitation Science and Engineering at Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital in Lincoln, Neb.

With physical therapist colleagues at Rancho, Perry established an observational system used by clinicians around the world to determine why patients are having trouble walking and how to manage the problem.

Her research on patients with severe deficits arising from neurologic and orthopedic injuries continues to guide present-day therapeutic approaches, said Burnfield, who helped Perry update her textbook, “Gait Analysis,” first published in 1992.

The first cases of post-polio syndrome were not seen until 1980, according to Perry, and they surprised doctors. The condition stems from further weakening of overworked nerves and muscles damaged years before by polio’s initial infection.

The same drive that had helped polio patients overcome the disability as children got in the way in adulthood, according to Perry, who instructed patients to downshift physically to protect themselves.

“As far as I’m concerned, I’ve never worked,” Perry told The Times in 1999. “I do what I like to do.”

The only child of a clothing shop clerk and a traveling salesman, Perry was born May 31, 1918, in Denver and moved to California the year she turned 6. She never married and had no immediate survivors.

At UCLA, she earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education in 1940. She taught swimming for one day before quitting to attend physical therapy school at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C.

After earning her medical degree in 1950, Perry was recruited to help launch Rancho’s rehabilitation program after completing her residency at UC San Francisco.

From 1972 to the late 1990s, she was a professor of surgery at USC’s medical school, where she established a scholarship for study of the human gait.

The no-nonsense Perry was seen as both an intimidating and inspiring teacher. Those who survived presenting a case before her were often given an unofficial award. They called it “the red badge of courage.”

A celebration of Perry’s life will begin at noon March 22 in the Support Services Annex Building at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, 7601 E. Imperial Highway, Downey.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.