Ralph S. Paffenbarger Jr., 84; his key study confirmed that exercise boosts longevity

Dr. Ralph S. Paffenbarger Jr., an epidemiologist whose landmark study substantiated the link between exercise and longevity and helped lay the foundation for the modern fitness movement, has died. He was 84.

Paffenbarger, a researcher at the Stanford University School of Medicine, died Monday at his home in Santa Fe, N.M., after a long battle with congestive heart disease, the university announced.

In 1960, he launched the College Alumni Health Study, which tracked the exercise habits of 52,000 men who had entered Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania between 1916 and 1950 as they moved through middle and old age.

Those who exercised vigorously, expending 2,000 calories a week — the equivalent of jogging or walking briskly for 20 miles — lived longer than those who didn’t, the study concluded in 1986.

His rule of thumb was that for each hour of physical activity, the exerciser gained an extra two or three hours of life.

The research also showed that those who actively engaged in sports had a lower risk of death from heart disease and other illnesses associated with aging. The exercisers had death rates a quarter to a third lower than those in the study who were least active.

“There’s not much more convincing people need. He showed that sedentary people are much more at risk, and the more they exercise, the better,” Dr. Allan Abbott, a professor at the USC school of medicine who focuses on fitness and physical activity, told The Times on Friday.

In a 1988 interview with Runner’s World magazine, Paffenbarger called the data a “natural history of ways of life and disease in America.”

His work influenced the 1996 Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity and Health, as well as exercise guidelines issued by the American College of Sports Medicine and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, according to Stanford.

He was a recipient in 1996 of the first International Olympic Committee prize for sport science. He received the award at the Atlanta Games with Dr. Jeremy Morris, a British researcher who also helped change the scientific and public understanding of exercise.

Men who take up exercise later in life appeared to receive the same benefits as lifelong exercisers, a finding that moved Paffenbarger to start running in the fall of 1967 when he was 45.

“It was terrible,” Paffenbarger told the Associated Press in 1996. “I was exhausted by the end of the block. I was delighted to be behind the junior high school, where no one could see me.”

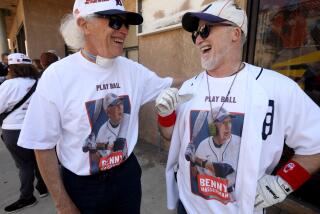

In spring 1968, he ran the first of 22 Boston Marathons, and he went on to run more than 150 marathons and ultra-marathons in all. After heart problems forced him to give up running in 1993, he took to walking in the hills around his home in Berkeley.

Ralph Seal Paffenbarger Jr. was born Oct. 21, 1922, in Columbus, Ohio, and served in the military during World War II.

After receiving a bachelor’s degree from Ohio State University in 1944, he graduated from Northwestern University’s medical school in 1947. He also earned a master’s degree and a doctorate in public health from Johns Hopkins University.

Early in his career, Paffenbarger researched polio for the U.S. Public Health Service. He was a professor of public health at Harvard in the 1960s and taught in the same field at UC Berkeley from 1969 to 1980.

In 1977, he joined Stanford as a professor of health research and policy and, after retiring in 1993, joined UC Berkeley’s department of human biodynamics. He also remained affiliated with Harvard and the ongoing study of college alumni.

A study finding in 1995 suggested that longevity is fostered by vigorous, but not nonvigorous exercise, which surprised leading researchers in the field.

“A little exercise is better than none, but more is better than a little,” Paffenbarger told the New York Times in 1995.

He published hundreds of papers on the relationship between exercise and longevity and delighted in applying his findings to his own life, wearing a pedometer late in life to track how far he walked every day. His second wife, JoAnn, whom he married in 1991, is a clinical nurse and ultra-marathoner.

Paff — as his friends called him — was a gentle yet tenacious soul.

“He was just this really nice guy. In the world of research, which can be competitive and backstabbing, he destroys stereotypes,” I-Min Lee, a Harvard physician and researcher who took over the direction of the study, told the Chicago Tribune in 2000.

Most of the men in Paffenbarger’s family had died in their 50s of heart disease, and his own longevity surprised him, the Tribune story reported.

Although he trained for his first marathon in World War II combat boots, running shoes soon became a wardrobe staple. Even after he stopped running, he bought one pair a year, on sale. When he had to dress up to receive an academic honor, he wore his black pair.

In addition to his wife, JoAnn, Paffenbarger is survived by four children from his first marriage and four grandchildren. His first wife, Mary, and two other sons preceded him in death.

A memorial service and reception will be held at the Stanford Faculty Club at 11 a.m. Oct. 6.

The family suggests donations to either the Harvard School of Public Health, College Alumni Health Study, 677 Huntington Ave., Boston, MA 02115; or to Stanford University, Department of Epidemiology for Mental Health Research, 326 Galvez St., Stanford, CA 94305.

valerie.nelson@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.