Time served -- and wasted -- for a nonviolent drug offense

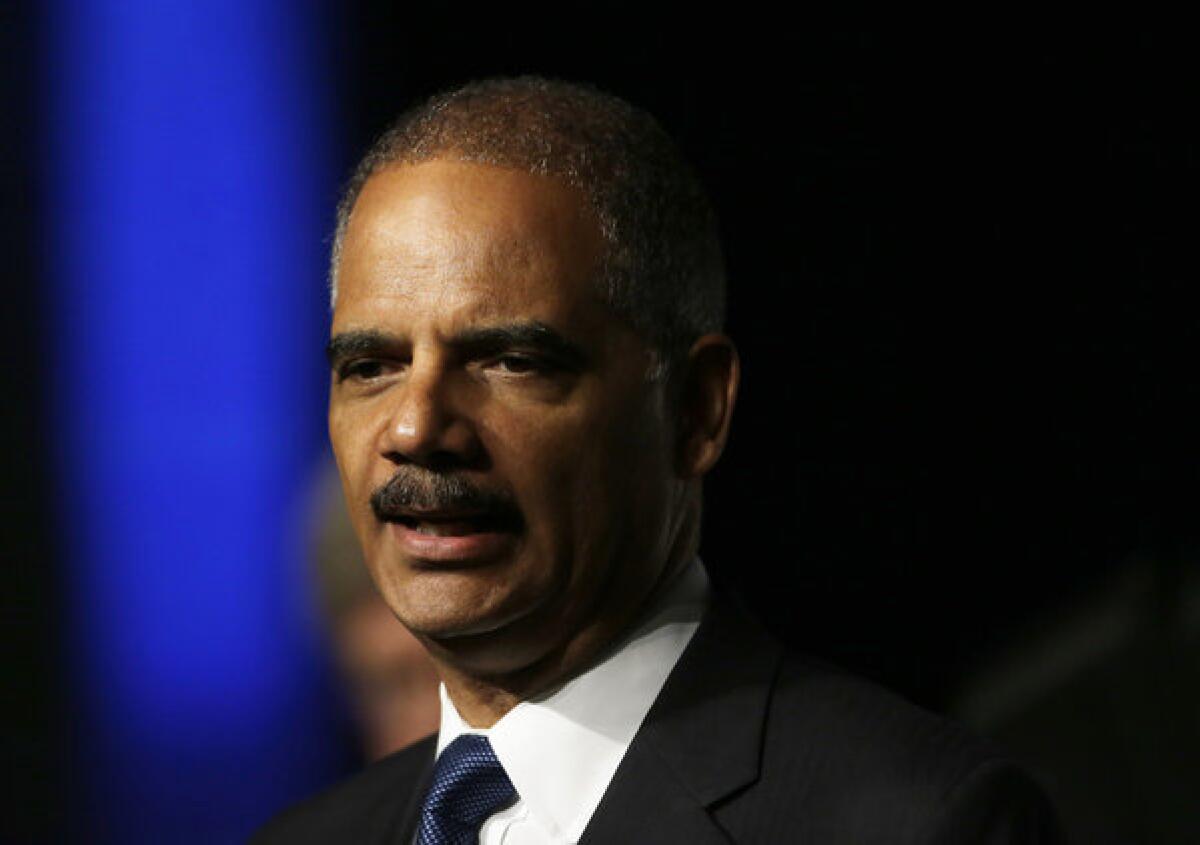

When I learned this month that Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. was proposing to change how the federal government charges and sentences nonviolent drug offenders, I thought to myself, “It’s about time.” I know a thing or two about time. I spent more than 16 years in federal prison for a nonviolent drug offense.

I do not have any excuses for my crime. In the early 1990s, my then-husband and I began using methamphetamine at a point in our lives when we should have known better. I am sorry to admit that I became addicted to the drug and then began selling it to others so that I could make some money. I was not a drug kingpin by any stretch, but I thought the extra money would help me keep my family together.

I was eventually arrested. The woman I sold drugs to pleaded guilty and cooperated with prosecutors in exchange for a shorter sentence. I knew I was guilty and was going to have to serve time in prison. What I did not know at the time was that federal mandatory minimum sentencing laws — and the federal guidelines based on them — would require so much time.

Federal prosecutors charged me with a conspiracy to sell 10 kilograms of meth, an amount I knew had been inflated by the cooperating woman. When I contested the drug amounts she had testified to at my sentencing, the judge took away any credit I would have received for accepting responsibility for my crime and added four more years for obstructing justice. In May 1994, I was sentenced to 19 years and seven months in federal prison. (The woman who cooperated received probation.)

I deserved to go to prison. I had broken the law. More important, I needed to go to prison because I desperately needed a wake-up call.

But I did not need nearly 20 years in prison to pay my debt to society and learn my lesson. The first few years of my incarceration, I focused on self-improvement. I began working toward an associate’s degree in business administration, which I achieved, and then continued on toward a bachelor’s degree in social science. I participated in the Prison Fellowship ministry and stayed in close touch with my family. I kept my spirits high by believing that there was no way I would serve my full sentence.

But there I sat year after year, and there were many other women just like me. We were sentenced to more time than some people who were convicted in federal court of murder, manslaughter or kidnapping. And once those first few years passed, we were mostly just killing time on the taxpayers’ tab. Many of us had young children who could have used our love and support, and having felt as if we failed them once, we were anxious for another chance. We couldn’t wait to lead productive lives. And yet the years kept marching by — slowly.

There is no parole in the federal system. The law allows prisoners to earn time off for good behavior; they cannot reduce their sentences by more than 15%. I earned the maximum amount of good behavior credit. I also sought to have my sentence commuted, but was denied three times. (The last rejection, from President Obama, arrived after I was already home.) I was released in 2010 after serving 16 years and one month.

Since my release, I have continued my education, provided child care so that one of my daughters could pursue her education and volunteered with a prisoner reentry group, and am working at an electronics recycling center. I knew I could make a positive difference and wanted to make up for lost time.

I know there are a lot of other women just like me who have paid their debt and gotten their heads straight but are still serving lengthy mandatory minimum sentences for drugs.

I needed prison, but I did not need to spend the majority of my adult life there. I hope Congress will work with the attorney general to reform our sentencing laws. Change is long overdue.

Debi Campbell was born in Long Beach. She now lives in Virginia.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.