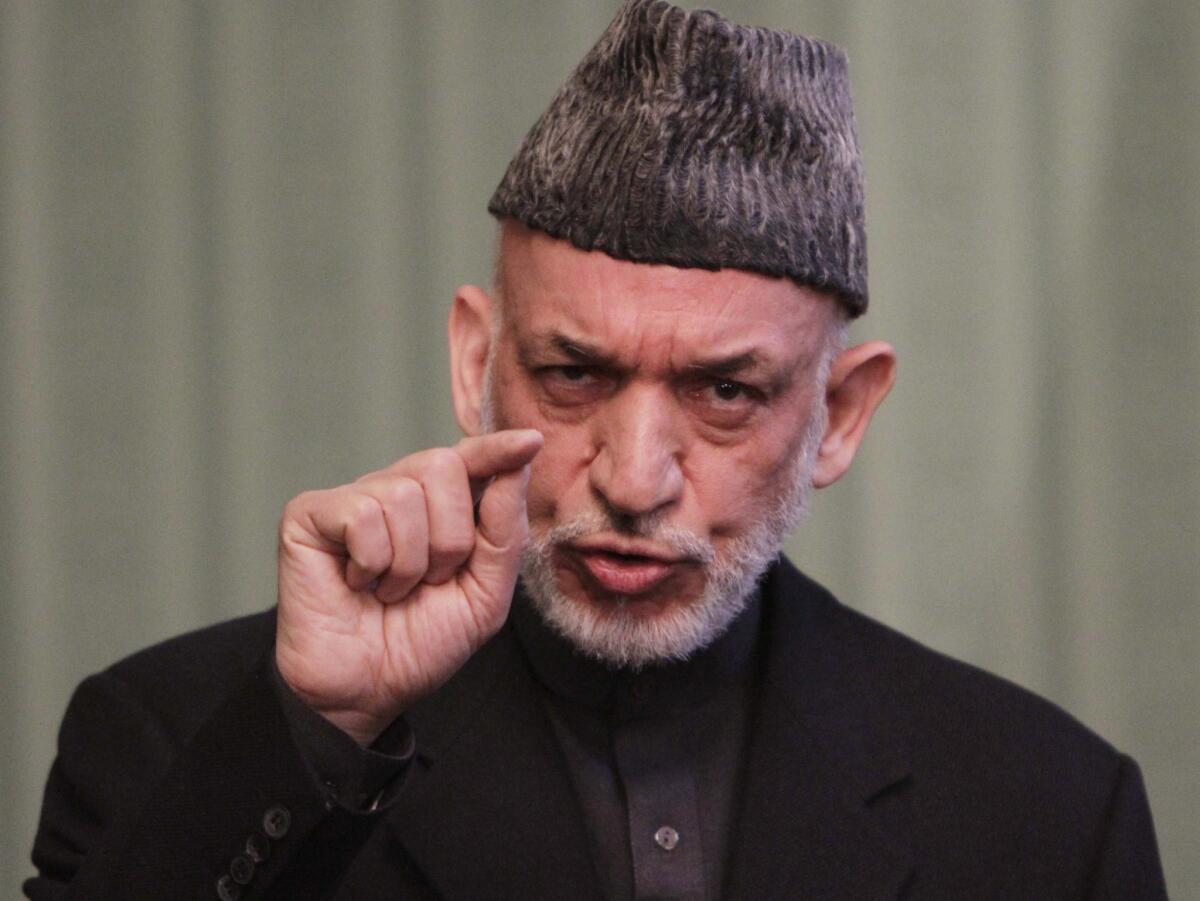

Hamid Karzai’s cozy history with the Taliban

If anyone is surprised that with each passing day Afghan President Hamid Karzai seems to veer more sharply away from the U.S. and toward the Taliban, it might be time to remember some history. Karzai himself was once asked to become a high-ranking member of the Taliban government.

His every word and deed of late seems designed to appeal to the Taliban leadership and its backers in Pakistan, and to fracture the partnership between Afghanistan and the American people.

In one recent display, he held a news conference for Afghan villagers who claimed U.S. bombing had killed a dozen neighbors on Jan. 15. They identified mourners in a photograph purportedly taken at a funeral the next day, Jan. 16. But it turned out the photo was from four years back. In fact, it has been featured on Taliban websites, according to the New York Times.

Karzai was indulging in just the type of heavy-handed propaganda we’ve come to expect of the Taliban itself. He has also ordered the release without trial of three dozen suspected insurgents, some of whom U.S. officers have tied to specific attacks. And, by his refusal to sign a security pact with the United States, he seems to be actively expediting the departure from Afghanistan of all foreign forces.

This behavior is not all born of current events. It is not some recently conceived hedging strategy pegged to the impending U.S. troop draw-down. Rather, it is entirely consistent with Karzai’s own past. That past, presumably known to U.S. officials, has shaped his actions since the Taliban regime fell in 2001.

I began noticing the pattern in 2003, when I lived in Kandahar, running a nonprofit founded by Karzai’s older brother Qayum. Repeated, perplexing anomalies in Hamid Karzai’s decision-making — his choices for filling certain positions, or the way he interacted with specific communities — were so egregious and inexplicable that I was driven to hunt for some underlying logic. I began asking family retainers, neighbors, tribal elders and former resistance commanders what Karzai’s relationship with the Taliban had been when the religious militia swept into the city in 1994.

The story I heard, with consistent details, took me aback.

In those days, Kandahar, like most of Afghanistan, was in turmoil. Resistance fighters, who had helped drive the Soviet army out of Afghanistan in 1989, had not disarmed and gone back to tending their orchards. They had turned on one another. Neighborhoods were plowed up in pitched battles, while travelers on the roads were shaken down at gunpoint for money or goods. “If you had five guys with guns, you were the mayor of your street corner,” a former bus driver named Hayatullah once told me.

In this context, according to several witnesses, Karzai began holding meetings with many of the proto-Taliban leaders, organizing them into a force that could gain control of Kandahar, and eventually the rest of the country. These meetings were taking place across the border in Quetta, Pakistan. And the Pakistani military intelligence agency, the ISI, which has long made use of Islamic extremism to further its policies, supported the project.

In October 1994, the Taliban moved on Afghanistan. “I lived next to the bus station in Quetta,” a former refugee named Shafiullah told me. “Busloads and busloads of them left for the border, army officers with them.” The Taliban and their Pakistani advisors fought one battle just inside the line, where they captured a weapons cache, then another in the small town of Takhta Pul, halfway to Kandahar. Within a week they owned the city.

One reason the assault went so easily was the work Karzai had done ahead of time. The strongest commander in Kandahar was a thick-bearded tribal elder named Mullah Naqib. For weeks before what amounted to the Taliban invasion, he and others told me, Karzai argued with him to stand his men down so the Taliban could come in. “He told me it was the best thing for Afghanistan,” Mullah Naqib recalled in 2004. “He said the Americans supported this.” Without Mullah Naqib’s tribesmen, no fighting force would last long against the ISI-supported Taliban.

Once in power, the Taliban leadership asked Karzai to be their U.N. ambassador, a position he later said he turned down. My Kandahar sources disputed that claim. And as it turned out, the U.N. never recognized Taliban rule, so the Kabul government could not send an ambassador. According to information found by journalist Roy Gutman in the U.S. National Archives, however, Washington launched a diplomatic demarche to ambassador-designate Karzai in December 1996, requesting the extradition of Osama bin Laden.

None of this is to say that Karzai personally shares the fundamentalist religious ideology espoused by the Taliban. I don’t think he is driven by any ideology at all. However, he has repeatedly marched with the Taliban when it has seemed expedient. As he suggested to the Sunday Telegraph’s Christina Lamb on Jan. 27, Karzai wants to matter.

U.S. officials and Afghan citizens alike should not assume they will be rid of his influence after next April’s presidential election.

Sarah Chayes, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment and a contributing writer to Opinion, lived in Afghanistan for most of the last decade and served as special assistant to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.