Op-Ed: The challenge for China’s Leninist emperor

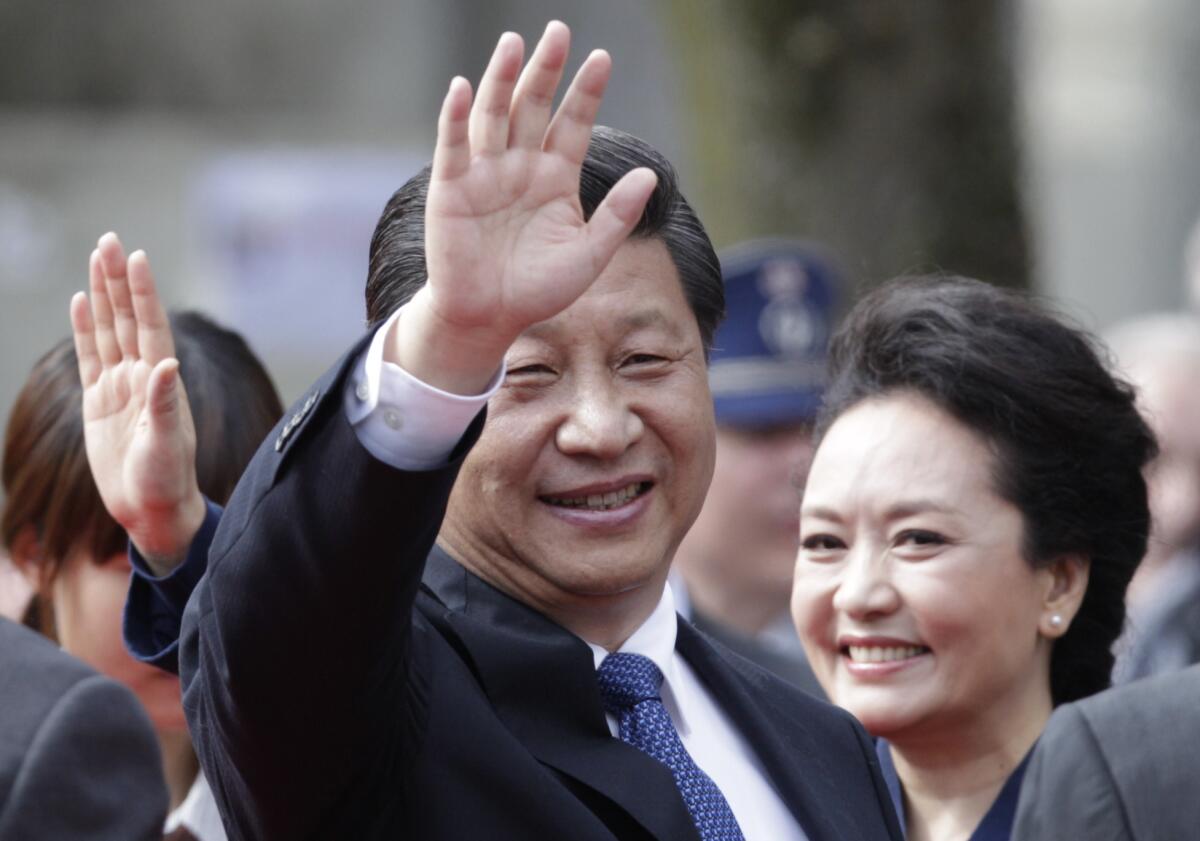

BEIJING — President Xi Jinping is leading an extraordinary political experiment in China. In essence, he is trying to turn his nation into an advanced economy and three-dimensional superpower, drawing on the energies of capitalism, patriotism and Chinese traditions, yet all still under the control of what remains, at its core, a Leninist party-state. He may be a Chinese emperor, but he is also a Leninist emperor. This is the most surprising and important political experiment on Earth. No one will be unaffected by its success or failure.

In 1989, as communism was trembling in Warsaw, Berlin, Moscow and Beijing, who would have predicted that 25 years later we would be poring neo-Sovietologically over the 60-point decision of the Third Plenum of the 18th Communist Party congress, so as to understand how the party leadership proposes to keep China both economically growing and politically under control?

Xi has moved decisively to strengthen central party power and his own position. Besides taking the traditional commanding roles in the military, state and party more rapidly than his predecessors, he has created at least four other central command committees — on economic reform, state security, military reform and, tellingly, the Internet. “More than Mao!” cries one disgruntled party reformer.

His anticorruption drive appears about to take down a former boss of the national security apparatus and high-ranking party member, Zhou Yongkang. China must, says the party’s propaganda, tackle the tigers as well as the flies. This may be taken as a token of seriousness about tackling rampant corruption at the highest levels. Or it could be seen as part of the traditional maneuvers of a new leader securing his power over real or potential factions inside the party. It is a purification but also a purge. Meanwhile, critical bloggers have their accounts deleted, dissidents are imprisoned and unhappy provinces are kept under a security lockdown.

But, you may exclaim, Beijing in 2014 is light-years away from Moscow in 1974, let alone 1934! Of course you are right. For every bit of the old there is a byte of the new. In Beijing or Shanghai, you wander through glitzy shopping malls to meet super-smart, sophisticated businesspeople, journalists, think tankers and academics who talk freely about almost everything. Executives and Internet millionaires speak Californian. Successful entrepreneurs turn to ancient Chinese history, Confucianism and Buddhism for post-materialist meaning.

There is conspicuous consumption, high fashion and a cosmopolitan lifestyle, but also national pride and a sense of historical optimism. Bright, ambitious students flock to join the Communist Party, not out of egalitarian conviction but for reasons of personal advancement mixed with patriotism. “In what sense, if any, is this a communist country?” I asked a young party member. “Well, it is run by the Communist Party,” he replied. This seemed to him an entirely sufficient answer.

The party explicitly recognizes that it needs more market forces. It has announced a bonfire of the red tape holding back small and medium-sized enterprises, although Chinese journalists remain skeptical about their capacity to go up against still dominant, politically well-connected state-owned enterprises. Li Keqiang, the able premier, clearly understands the daunting economic challenges identified by Chinese and foreign experts, such as a burgeoning debt burden, a real estate bubble and too little demand coming from domestic consumption.

So my point is not that there is nothing new under the Chinese sun. It is that we should not lose sight of the old inside the new, and imagine that the politbureaucratic language of the Third Plenum is purely formalistic. Wherever you turn, the party secretary retains a decisive voice. There are Communist Party committees or cells inside private companies, including foreign-owned ones. Many are explicitly acknowledged, some probably not.

As Xi and his colleagues have moved to consolidate their power and set their course, it has become clear that this reform will be implemented through reinvigorated party control. For years, many of my friends — Chinese and foreign, party members and outspoken critics — have been looking for evolutionary steps toward a greater separation of state and party, more genuine rule of law (as opposed to mere legalism, or rule by regulation), a larger space for nongovernmental organizations and more open public debate.

A few shards from those hopes remain in the current reform package. But there is not much. In a party directive known by the wonderfully Orwellian title of “Document No. 9,” seven supposedly subversive ideas are listed that the good comrade is not to countenance. They include constitutional democracy, universal values and civil society.

The Chinese Question is no longer could evolutionary political reform, gradually increasing transparency, constitutional-type balances, freedom of expression and civil society dynamism be used to complement and reinforce economic reform? Rather, it is can a reinvigorated party-state, harnessing in unprecedented fashion the energies of capitalism, patriotism and older Chinese traditions succeed in mastering the ever more difficult challenges of continuing modernization?

And the answer? I spoke to two of the most experienced foreign correspondents in China, and their diagnosis of the problems was almost identical, and their predictions spectacularly different. One thinks the party can still keep the show on the road, with skillful management of state-led development. The other foresees economic meltdown, social revolt and political upheaval.

In short, nobody knows. But at least we should be clear about the question.

Timothy Garton Ash is professor of European studies at Oxford University, a senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and a contributing writer to Opinion. His latest book is “Facts Are Subversive: Political Writing From a Decade Without a Name.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.