Op-Ed: Evolving awareness is cause for same-sex-marriage optimism in court

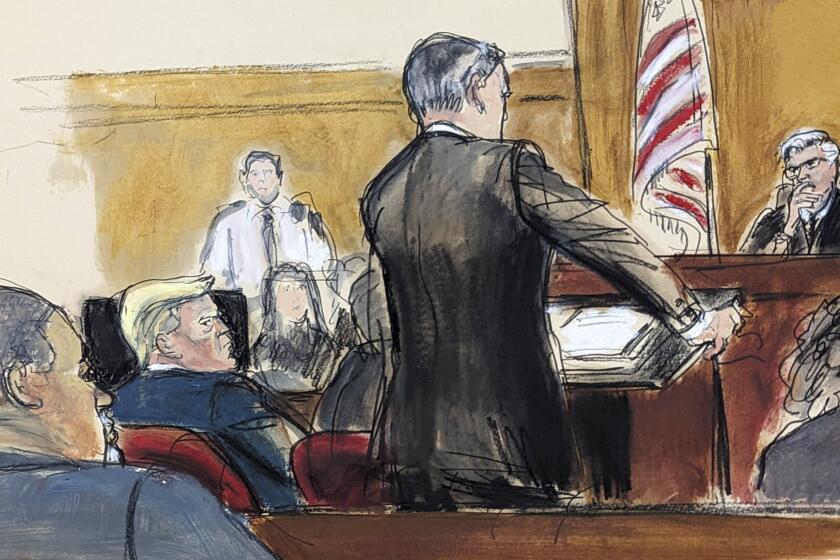

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the Ohio case of Obergefell vs. Hodges, as well as three related cases from Kentucky, Michigan and Tennessee. The court is then expected to decide whether the Constitution requires states to grant gay people the same rights in marriage as straight people. Most court watchers believe that the justices will rule in favor of marriage equality. But just a few years ago, this now widely anticipated result seemed almost completely out of reach.

During my career, I have had two opportunities to argue for the constitutional right of gay couples to marry. The first time was before New York’s highest court in 2006. We lost. The second was in federal court in Mississippi in 2014. We won. I also argued in United States vs. Windsor before the Supreme Court in 2013 and won, but that was slightly different since it concerned whether the federal government had to recognize the marriages of gay couples who were already married under the laws of their home states.

So what changed in the nine years between 2006 and now? It’s actually a lot easier to identify what did not change. The legal arguments we made certainly did not vary. And there is no difference between now and 2006 (or even 2003, when Mary Bonauto won the first marriage equality case in Massachusetts) in terms of the constitutional principles invoked.

In 2006, we argued, just as the pro-LGBT rights lawyers are arguing today, that the bedrock American principles of equal protection and due process of law require gay couples and families to be treated the same as everyone else. After all, we argued, there was no dispute that gay couples were having children and raising families, who should have the same benefits and protections as those headed by straight parents. But the New York court was not convinced. It ruled instead that “the Legislature could rationally decide that, for the welfare of children, it is more important to promote stability and to avoid instability in opposite-sex than in same-sex relationships.”

When we repeated these same arguments in 2014, we got a completely different reception. Here, for example, is how the judge in our Mississippi case framed the issues:

“Can gay and lesbian citizens love?

Can gay and lesbian citizens have long-lasting and committed relationships?

Can gay and lesbian citizens love and care for children?

Can gay and lesbian citizens provide what is best for their children?

Can gay and lesbian citizens help make their children good and productive citizens?

Without the right to marry, are gay and lesbian citizens subjected to humiliation and indignity?

Without the right to marry, are gay and lesbian citizens subjected to state-sanctioned prejudice?

Answering Yes to each of these questions leads to the inescapable conclusion that same-sex couples should be allowed to share in the benefits, and burdens, for better or for worse, of marriage.”

The legal arguments or principles did not change between 2006 and today; what did change was the ability of judges to actually hear what we were saying.

In the Windsor case, because of the Defense of Marriage Act, my client, Edie Windsor, was forced to pay more than $350,000 in estate taxes when her spouse, Thea Spyer, died, even though if Edie had been married to “Theo” rather than “Thea,” she would not have had to pay a penny. We argued there that if the government chooses to bestow a set of benefits and duties when people marry, then all Americans — gay or straight — must be treated equally with respect to that status.

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, in his opinion for the Supreme Court, agreed. He explained that “DOMA writes inequality into the entire United States code” since it “touches many aspects of married and family life, from the mundane to the profound.”

Kennedy suggested that “interference with the equal dignity of same-sex marriages was more than an incidental effect of DOMA. It was its essence.” DOMA was therefore “invalid, for no legitimate purpose overcomes the purpose and effect to disparage and to injure those whom the state, by its marriage laws, seeks to protect in personhood and dignity.”

As for the children of gay parents, Kennedy concluded that DOMA “humiliates tens of thousands of children now being raised by same-sex couples. The law in question makes it even more difficult for the children to understand the integrity and closeness of their own family and its concord with other families in their community and in their daily lives.”

At my oral argument before the Supreme Court in Windsor, Justice Antonin Scalia characterized the dramatic shift in our society’s understanding of gay people as a “sea change.”

While I don’t often agree with Scalia’s views in cases involving LGBT rights, that description was absolutely right. There can be little doubt that the reason for the sea change is that most Americans now have a friend, a neighbor, a family member or colleague who happens to be gay. Once you know and respect someone who is gay, it is very hard to accept the fact that they can be discriminated against simply because of who they are.

In other words, as Evan Wolfson of Freedom to Marry recently observed, once you accept, as the Supreme Court did in Windsor, the equal dignity of gay people, then it’s “clear that there are no good arguments against marriage equality.”

Marriage can matter as much in life as in death, as made clear by the stories of Edie Windsor and of Jim Obergefell, the plaintiff in the Ohio case. Obergefell and his longtime, terminally ill partner, John Arthur, wanted so badly to be married that they chartered a medical plane from Ohio, where they lived, and where marriages between gay people were not permitted, to Maryland, where they could wed. When Arthur died, Ohio refused to correct his death certificate to accurately state the fact that he’d been married to Obergefell.

By stubbornly insisting that there must be a blank space on Arthur’s death certificate where Obergefell’s name should be, Ohio not only denied these men the equal protection of the laws in life but also seeks to deny them dignity even in death.

After I finished arguing Windsor in March 2013, I knew in my heart that we had won. I am similarly confident about the current Supreme Court cases. The majority of Americans (including the majority of the Supreme Court justices) now agree that gay people deserve to be treated equally under the law, whether in life or in death.

Roberta Kaplan, a partner at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, is the author of “Then Comes Marriage: United States v. Windsor and the Defeat of DOMA,” to be published in October.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.