Opinion: Jonah Goldberg and the elitist argument against high-turnout elections

In his election day column, Jonah Goldberg unabashedly flies the flag for the political elite when it comes to one of the fundamental acts of citizenship: voting.

You might think that Goldberg is an unlikely advocate for this stratum of society, given how often his columns have used the word “elite” to convey scorn. But Jonah has a long history of raging against the efforts to increase turnout, arguing that it would be better to have fewer voters than having uninterested and uninformed ones.

It’s tempting to think that his position springs from the effect that demographic change is having on Republicans. The fastest growing segments of the population tend to vote solidly Democratic, so the more people who vote, the better the chances are for Democrats to win. The 2008 and 2012 presidential elections are cases in point.

But I’ve heard the same argument from some of my decidedly not Republican colleagues on The Times’ editorial board, along with many other people who pay close attention to politics. They’re worried about the influence that misleading, dishonest campaigns have over “low-information voters.” They also worry about people knowing so little about the lower-profile races on the ballot that they make their decision solely on the candidates’ names and titles.

A textbook example is a 2006 race for Los Angeles County Superior Court judge that pitted an inactive attorney turned bagel baker against a veteran judge. The judge had a foreign-sounding name -- Dzintra Janavs -- and the bagel baker’s name was Lynn Olson. Guess who won?

Considering how long and crowded the ballots often are, however, even well-informed voters can’t be expected to become well versed in every race. And so much money is being spent these days on campaigns, it’s hard to avoid being brainwashed by a deceptive ad that’s aired dozens of times in the days before an election.

Even some of the most plugged-in readers of this blog have stumbled over which propositions are backed by which special interests.

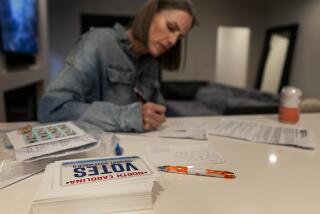

We’d all be better off if everyone prepared as assiduously to vote as they do for a driver’s exam or a major appliance purchase. But there’s still enormous value in getting as many people to vote as possible, even if they’ve spent the previous two years in blissful ignorance of all things political.

When people vote, they’re more invested in the outcome -- particularly when the candidates and ballot measures they support win. Their vote gives them a sliver of ownership, however tiny, in the government they’ve elected, as well as a measure of responsibility. Consider it the opposite of the “Don’t blame me, I voted for the other guy” bumper stickers.

A large turnout also gives the winning candidates a more credible claim to having a mandate from the public to implement their platform. By contrast, when the winning candidate is backed by less than 15% or 20% of the electorate, he or she can’t assume that the public even knows what the campaign was about.

Finally, each voter sends an important signal to elected officials just by casting a ballot. They’re saying, “You are answerable to me.” Those who don’t, meanwhile, are implicitly granting those who are elected the freedom to do as they please.

The enormous size of California and Los Angeles County make it easy to justify not voting. A single vote isn’t likely to decide any race here. And it’s no mean feat to decide how to fill the dozens of InkaVote bubbles on the typical ballot here. But voting affects more than the outcome of the races. It creates a symbolic bond of responsibility between voters and elected officials, but the bond is only as strong as the turnout.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.